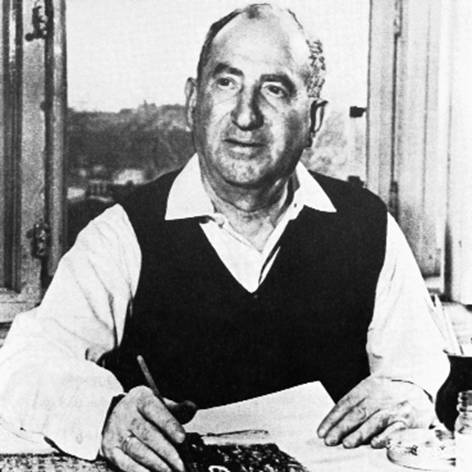

Anatoli Kaplan

Gallery

Recollections of a Miracle

(A. Shedrinsky about Kaplan)

The name of Anatoli Kaplan (1903-1980) became widely known in the late 1960s and in the early 1970s, when his works were constantly displayed at exhibitions in Leningrad and across the entire Soviet Union. By that time he had already won worldwide recognition and his works were enjoying great success in England, Germany, USA, Canada, Austria, and Italy.

Kaplan did not fall into the mainstream of official Soviet art policies in the difficult 1950s, and was not carried away by the 1970s avant-garde innovations. His life and creative path were not particularly affected by dramatic events, and were not marked by active opposition to the ruling dogmas. In his work, he remained quite steady and consistent.

Kaplan was often referred to as an artist whose heyday came late. And, indeed, he first entered a lithographic studio at the age of 40, took up ceramics when he was 65, later got involved with pastels, and started using drypoint after the age of 70. He always demonstrated great skills and added his own individual touch to various techniques and materials, be they graphite, gouache, pastel, lithographic stone, etching, or ceramic layers and sculpture, which he took up in the last years of his life.

The artist was born in Belorussia, in the small town of Rogachov. His childhood reminiscences served as the basis for his creative activity and became an inherent part of his spiritual world. Aspects of folk life together with ancient national traditions shaped the images that predetermined the development of Kaplan’s art.

From 1922 to 1927, he studied at the Petrograd Academy of Arts. He lived in this city – later called Leningrad, now Saint Petersburg – for the rest of his days. Among his teachers were such well-known artists as A. Rylov, N. Adlov, and K. Petrov-Vodkin. He tried different kinds of art, such as industrial drawing and book illustrations. At that time, Kaplan was particularly fond of charcoal, which allowed him to produce a mild velvety coloring; pencil was actively employed to create a thick stroke.

The main landmark in Kaplan’s creative biography was his admission to the experimental lithographic workshop of the Leningrad Branch of Artistic Union (LBAU). There, not only his professional experience was enriched, but the very friendly atmosphere gave him a constant creative stimulus. It was in the lithographic workshop that Kaplan’s first cycle of work, entitled “Kasrilovka”, came into being (1937-1940). The name was taken from Sholem Aleichem, but his actual inspiration was the town of Rogachov. The everyday life of Jewish shtetl at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, with its specific appearance and peculiarity of Jewish life, predetermined the composition and topics of Kaplan’s first cycles.

One would have expected that the simple and sometimes wretched existence of these old shtetl’s inhabitants would evoke in Kaplan’s works a feeling of sorrow. But even in those prewar years, the artist’s works displayed a pure lyrical feeling poeticizing the past; the coziness and the world of memories became the tuning fork of his creativity. In his later works, everyday motifs, eternal human attachments and affection, would be filled with deeper meaning to become metaphoric milestones of human life as construed by the artist.

During WWII, Kaplan was evacuated to the Ural Mountains. There he taught and displayed his works at exhibitions. He portrayed the mass-scale shooting of women and children, the killing of old people. The sketches came one after another. And many of them show the unfamiliar rigorous Ural countryside, small settlements and huge factory complexes. In 1944 the artist returned to Leningrad. The first works belonging to a series of lithographs “Leningrad Townscapes” deal with Leningrad during the war: the blacked-out city, demolished buildings, dredges on the Fontanka river.

The years from 1953 to 1963 became the key decade for the artist. This period was notable for his tireless attempts to find his own model of the world and man, to reveal and consummate the most typical traits of the graphic form. For many years Kaplan linked his artistic life with Sholem Aleichem – one of the writers who was spiritually closest to him and whose world vision was akin of his. “The Enchanted Tailor,” “Tevye the Dairyman,” “The Song of Songs,” “Stempenu,” and even “Stories for Children” found a response in his art and were quite distinctively treated by him.

At the same time (in the late 1950s – early 1960s), the so-called “folklore cycles” were carried out by Kaplan. In these subjects, he deliberately simplified the form. Samples of enamel art, carvings and ornamental jewellery took on a new meaning, and his profound penetration into folk art transformed the ethnographic material into aesthetic culture. The marvelous “Little Goat”, in which the artist personified the coziness and poetry of bygone days, became the peak of his folklore stylistics.

In such 1960s series of illustrations as “Tevye the Dairyman”, “Stempenu” and “Lame Fishka”, the “eternal” motifs always present in Kaplan’s art can be seen more and more clearly: birth, love and death form a closed circle that keeps repeating itself, and is embodied in different aspects of the human existence. In the cycle “Tevye the Dairyman”, relations between the painter and the text undergo certain transformation and are transferred to another level. And it is not the unfolding of the plot, but the strenuousness of the spiritual life and the figurative significance of the characters that come to the foreground.

Still more complex are Kaplan’s interrelations with the literary source in the cycle dedicated to Sholem Aleichem’s novel “Stempenu” (1963-67). The plasticity of the cycle is unusual. The forms are generated as if on impulse. A phosphorescent surface emerges and a mysterious depth becomes visible. The multiformity of textures creates this magic, formed by the fluctuations and overflowing of lines of light, piercing the patches of darkness. Interior and objects, their existence in a humanized medium, carry some symbolical meaning.

In the cycle of lithographs dedicated to Moykher-Sforim’s “Fishka the Lame”, Kaplan turned to the old art of carved stele, which consists of ornamental design, illustrative forms and script. The faces of beggars, wanderers and cripples, orphans and paupers are visible on the reliefs carved on tombstones. Their earthly travails are, in Kaplan’s works, illuminated by the light of spirituality and compassion. The artist gives them a certain majesty, a detachment and composure in the realm of dreams and eternity.

The last decade of the artist’s life was remarkable for his search for innovations and solutions predetermining his evolution. Unusual for a man of 60, he displayed daring new techniques and materials, and manifested afresh his unique artistic ego in the way he employed them.

In this period, Kaplan’s art acquired new treats. The vigor of his flexible lines increased, as did the contrasting character of his silhouettes. His pictorial medium, so typical of his previous drawings, was gone. For Kaplan, drawing became all the more a priority in his last decade. His strict, minimalistic drawing style of this time was marked by a certain formality.

In the late 1960s, Kaplan was still actively involved in lithography, such as in his cycles of illustrations for the “Short Stories” (1967-69) by I. L. Peretz, “Stories for Children” by Sholem Aleichem. But as if having exhausted all the resources of this technique, Kaplan came full circle by taking up graphite, black and brown pencils, and charcoal again. In this respect, his two last cycles were like a conclusion or final summing up. His illustrations for “Levin’s Mill” by I. Bobrovsky (1975) and “Nathan the Wise” (1977) by G. Lessing display a somewhat different approach to graphic art. The distinctive “purification” of the image from all that is specific and characteristic took place in the final cycle of illustrations to Lessing’s play. The heroes’ appearances are noble, exalted, and majestic.

In the 1970s, Kaplan returned to his first principles, but he achieved this through a spiral, where each loop had become a new plastic medium, a renewed form that took the viewer to a higher spiritual plane. The artist turned again to “Reminiscences of Rogachov” (1973-79), made a series of sheets to Shostakovich’s vocal cycle “Eleven Songs from Jewish Folk Poetry”. He searched tirelessly for innovations in the field of technique, color and material.

Experts often tend to compare Kaplan with Chagall. This comparison is not entirely well-grounded. Kaplan created his own world, his own system for interpreting reality, which was directed toward the past and based on a continual returning to the sources of folk culture. From one year to the next, his world vision grew more and more complex, as his style took shape and improved. He can hardly be called a realist. Kaplan is rather closer to the realm of “conditionally real” understanding, which he spoke of in the 1930s. That is why his themes taken from everyday life turn into diverse metaphors containing the notion of transcendental human values. Today, Kaplan’s art belongs to the whole world. His works are kept in museums of many European and American cities.