Yiddish and Yiddishkeit

There are two related words in Yiddish: “yiddishkayt” (often spelled in English as “yiddishkeit”), which literally means Jewishness as a tradition and culture, and “yidntum”, which means Jewry, the Jewish people considered collectively. While English allows us to preserve the difference between these two terms, they are conflated in some other languages, including the Hebrew word “yahadut” and the Russian word “yevreystvo”.

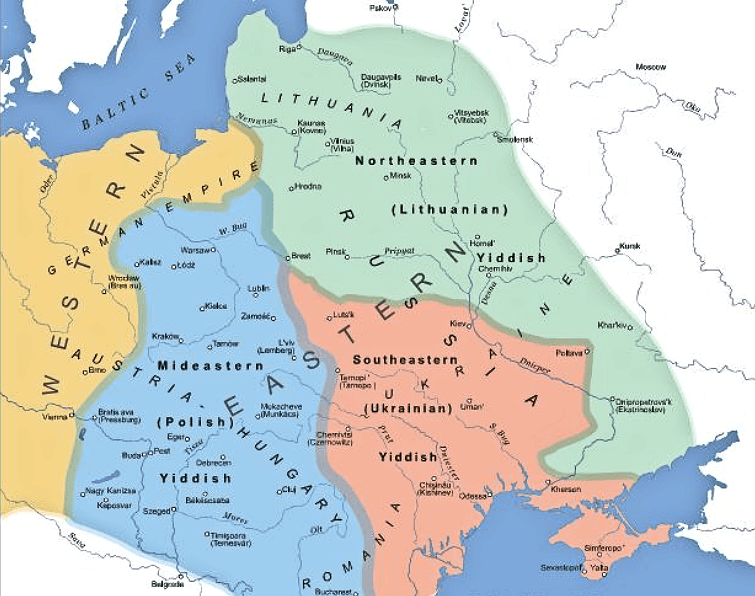

Yiddishland

(YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe)

At the same time, the word “yidishkayt” also appears in modern Hebrew and successfully competes with “yahadut”, when it comes to informal, sincere attitudes of Jews towards Judaism, not necessarily linked to official religious structures. In English and Russian this word is also situationally used in the same sense. In the original language – Yiddish – it is simply a derivation of the word “Jew”. However, when used in other languages, it expresses the organic connection between Yiddish and Yiddishkeit, which literally catches the eye.

In the Ashkenazi version of Judaism, the Yiddish language itself has become, without exaggeration, an important element of religious life. The older Jews who acted as the guardians of the Jewish tradition a few decades ago were native Yiddish speakers and used Yiddish terms, even when they spoke a foreign language, to express most concepts related to the traditional Jewish life – from holidays to cuisine.

New generations of Jews who grew up in the countries where the families had emigrated, or in the ruins of the original Yiddishland, rapidly became assimilated to the surrounding cultures and became secularized. Yet, Yiddish remained for them associated with the old traditions of the ancestors.

Yiddish now plays an exceptionally important role in the ultra-Orthodox religious Jewish communities of the United States, Israel and some other countries, where it remains the main language of everyday communication.

This role is multifaceted. First of all, Yiddish in such communities preserves the living continuity of the old Jewish tradition that flourished until recently in Eastern Europe. Secondly, it also preserves the traditional internal bilingualism that existed in Jewish communities for centuries, where Yiddish was the Jewish language of daily life, while Hebrew was the language of Jewish religion and sacred texts.

In religious Jewish terminology, it is about the division between holiness (koydesh) and everyday’s mundanity (khol). Finally, Yiddish maintains the separation of its speakers from the rest of the world, including secular and modernized religious Jews who switched to non-Jewish languages or to modern Hebrew. This separation naturally prevents the Yiddish speakers from becoming modernized. It’s worth to note that from the viewpoint of the ultra-Orthodox Yiddish speakers modern Hebrew is also perceived as a secularized, profane form of the sacred language artificially constructed by the Zionists.

Even in those ultra-Orthodox communities, where most members have switched to non-Jewish languages or Hebrew in their daily life, proficiency in Yiddish is considered prestigious. Yiddish is still taught in yeshivas by some reputable rabbis. A number of works of prominent rabbis who lived quite recently were written and published in Yiddish. Isolated Yiddish words are commonly found in the commentaries to religious texts written in Hebrew by the rabbis of older generations. Such texts, together with the commentaries, are still studied today. One notable example is the popular halakhic work Mishnah Brura by Rabbi Yisrael-Meyer Kagan (1838–1933) known as Chofetz Chaim (and who, by the way, authored several tracts entirely in Yiddish). Various religiously-themed Yiddish folk songs remain popular – and their popularity is not limited to ultra-Orthodox Jews. It is not surprising that those who wish to join an ultra-Orthodox religious community – especially a Yiddish-speaking one – actively study the language.

Yiddish-speaking ultra-Orthodox Jews have created their own Yiddish press and literature. Yiddish readers outside of those communities are familiar with the American Hasidic writer and blogger whose pen name is Katle-Kanye (meaning “a simple man” in Talmudic Aramaic).

At the same time, the ultra-Orthodox Yiddish speakers tend to ignore the entire modern and secular Yiddish culture that has already been flourishing for 150 years. Their Yiddish literature and press retains archaic non-standardized forms of spelling and purely dialectal grammatical forms. Moreover, it is infused with borrowed English words absent in literary Yiddish. This peculiar form of the language is often called “Hasidic Yiddish”, because the ultra-Orthodox Yiddish literature and media is dominated by certain groups of Hasidim.

Despite these oddities, cultural activities of the ultra-Orthodox attracted a growing interest among secular Yiddish enthusiasts in the recent years. After all, thanks to these communities, Yiddish continues to live as a natural spoken language and, contrary to popular belief, is not in immediate danger of extinction.

Some young folks who grew up in ultra-Orthodox communities and for whom Yiddish is their native language, became actively engaged in the treasures of the modern Yiddish culture. Quite a few contemporary secular Yiddish authors and activists have an ultra-Orthodox background. Examples include the Israeli actor Mendy Cahan (born in 1965 in Antwerp); the bilingual English and Yiddish American poet Yermiyohu-Aron Taub (born in 1967 in Philadelphia); the bilingual Hebrew and Yiddish Israeli poet Avisholom fun Shiloakh (born in 1991 in Bnei Brak).