Yiddish and Holocaust

According to a common saying based on a wordplay that if Hebrew is loshn-koydesh (the sacred language), then Yiddish is loshn-kdoyshim (“the language of the saints”). The word kdoyshim designates in Hebrew Jews who were killed for being Jews.

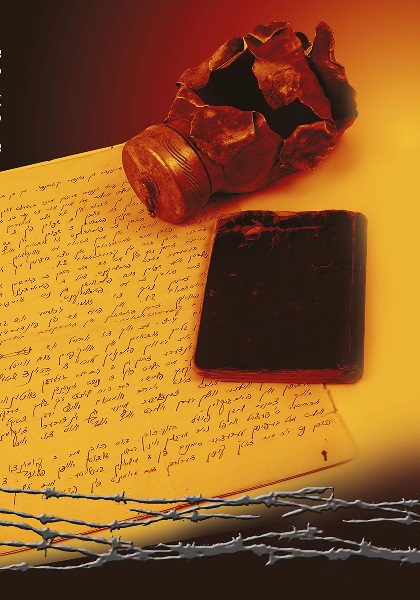

The soldier’s flask, in which Zalman Gradovsky (1908/1909 – 1944), a prisoner of the Birkenau-Auschwitz concentration camp, hid his Yiddish diary records written before his death. On the orders of the Nazis, Gradovsky was forced to serve in the Sonderkommandos units. After the liberation of the camp by the Red Army, his flask containing the dairy was discovered in the ashes in front of the crematorium.

Indeed, the vast majority of the victims of the Holocaust were Yiddish speakers, although the Nazis intended to kill all the Jews, regardless of the language they spoke, be it Yiddish or some non-Jewish language, including German. For example, the vast majority of Greek Jews spoke the Jewish-Spanish language knows as Ladino. In Israel, the Holocaust is called the Shoah, the national catastrophe of the European Jewry.

Six million Jews were killed during the Holocaust, which also destroyed Yiddishland, the extraterritorial country, which had existed for centuries across several Eastern European countries, where Yiddish was spoken not only by Jews, but even by some of their non-Jewish neighbors. In some districts of the Pale of Settlement, the proportion of Jews among the general population exceeded 20%.

It was a catastrophe that destroyed not only people, but also the unique European Jewish civilization, an entire world. In Yiddish, the Holocaust is called the Khurbn (literally, destruction). The same word is also used for the destruction of Jerusalem and its Temple by the Romans in 70 CE, and it means a destructive event of a truly apocalyptic scale with devastating consequences.

It is no coincidence that the Russian-speaking Jewish poet Naum Korzhavin (Nekhemya Mandel, 1925‒2018) wrote in 1945:

The world of Jewish shtetls…

Nothing is left of them,

As if Vespasian

passed here

amid fires and rumble.

After the catastrophe that hit the European Jewry, the remaining speakers of Yiddish, along with their culture, torn from the historical Yiddishland and scattered around the globe, became “emigrants from nowhere”. As for the Jews who survived the Holocaust and remained on the territory of the former Yiddishland, their children grew up on the ruins of a destroyed civilization, absorbing only fragments of its cultural heritage.

Nostalgia for the lost Yiddishland led to a certain romantic idealization of the Jewish shtetl, which became the main symbol of Yiddishland in general, although Ashkenazi Jews lived not only in shtetls. Perhaps, the most prominent artistic expression of this romantic idealization is the famous Broadway musical Fiddler on the Roof, written in the early 1960s by Joseph Stein, an American-born son of Jewish emigrants from Yiddishland. The musical is based on Sholom Aleichem’s stories about Tevye the Dairyman.

Another clear demonstration that the significance of the cultural tradition of the original Yiddishland, destroyed by the Holocaust, received a universal recognition, is the fact that the Yiddish writer Isaac Bashevis-Singer (1902‒1991) was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1978. In its decision, the Nobel Committee proclaimed that he deserved the prestigious prize “for his impassioned narrative art which, with roots in a Polish-Jewish cultural tradition, brings universal human conditions to life.”

The plots in many of Isaac Bashevis-Singer’s works are set long before the Holocaust. However, the Holocaust is always implicitly present in them, as in almost all works of Yiddish literature written during the second half of the 20th century. Even when their plot unfolds in Yiddishland long before the 1930s and 1940s, both the author and reader can not refrain themselves from recalling from time to time the thought that this literary works describe a destroyed world that no longer exists.

Yiddish literature continued to be produced even during the Holocaust itself. An important place of the Holocaust literature is Yitzchok Katzenelson’s poem “The Song of the Murdered Jewish People” (“Dos lid funem oysgehargetn yidishn folk”). The poet and playwright Yitzchok Katzenelson (1886‒1944) perished in Auschwitz.

The anthem of the Jewish partisans is performed every year in Israel, during the official mourning ceremonies on the Holocaust Remembrance Day. It was written in Yiddish in the Vilna Ghetto by the young underground fighter Hirsh Glick (1922‒1944). In Israel it is sung in the Hebrew translation made by the great Israeli poet Abraham Shlonsky (1900‒1973), who was also born in Yiddishland. It is also sung in the Yiddish original, in the language of the fighters who fought for this country of Yiddish, which is now wiped off the face of the earth. The anthem begins with the words “Zog nit keynmol, az du geyst dem letstn veg” (“Never say that you’re going your last way”).

Another song performed in Israel on the Holocaust Remembrance Day in both Yiddish and Hebrew, is Mordechai Gebirtig’s prophetic song “S’brent“(“Our shtetl is burning”). The famous poet and songwriter Mordechai Gebirtig (1877–1942) who wrote it in 1936, before World War II, was killed during the liquidation of the Krakow Ghetto.

The song ends with a powerful call for active resistance against the enemies who threatened the very existence of the Jewish people, resonates in the hearts of contemporary Israelis:

S’brent, briderlekh, s’brent!

Di hilf iz nor in aykh aleyn gevendt.

Oyb dos shtetl is aykh tayer,

Nemt di keylim – lesht dos fayer,

Lesht mit ayer eygn blut,

Bavayzt, az ir dos kent!

It’s burning! Brothers, it’s burning! Help depends only on you: if the shtetl is dear to you, take the tools, put out the fire. Put it out with your own blood — show that you can do it!

Zalman Gradowski. In the Midst of Hell. Notes Found in the Ashes near the Furnaces of Auschwitz