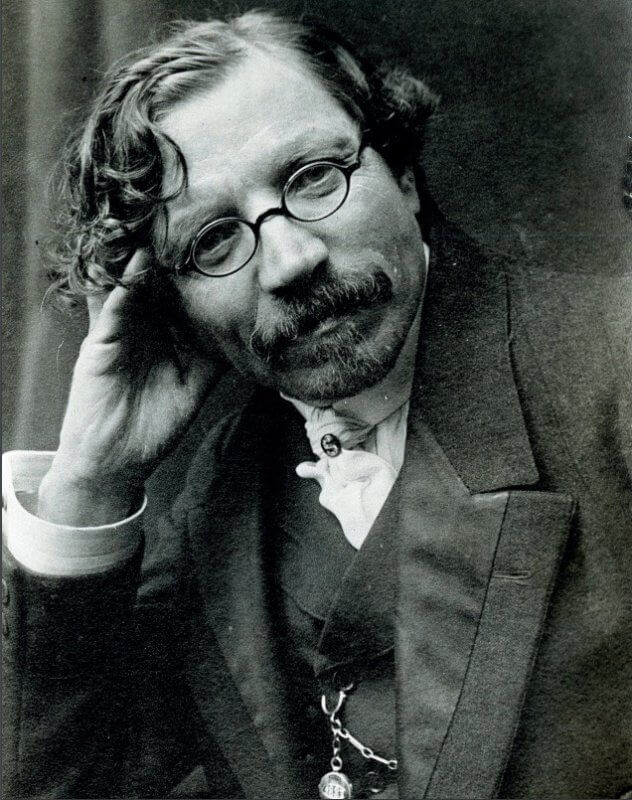

Sholem Aleichem

Collected Writings

(in Yiddish)

Sholem Aleichem

Monument and Prize

Archive

Sholem Aleichem has become known as the most important symbol of Yiddish literature. To some degree, it is due to the fact that, unlike the other two classics of Jewish prose, namely Mendele Moykher-Sforim and Yitskhok Leybush Peretz who wrote both in Hebrew and Yiddish, the language of Sholem Aleichem’s works was almost entirely Yiddish. One should also not forget that he was the least “elitist”, the most “democratic” of our three classics.

The vivid and incredible images of Tevye the Dairyman, the luftmensch Menachem-Mendl, Yossele Solovey, the villages of Kasrilovka, Anatovka and others, all created by Sholem Aleichem, were widely portrayed on the stage and on the screen – not only in Yiddish, but also in Hebrew, Russian, English and many other languages. Few writers can compete with Sholem Aleichem in the number of languages into which their works have been translated.

In the Soviet Union, each national minority was entitled to a literary classic (sometimes two), and such a classic served as the main symbol of that respective people’s literature and culture in general. The works of the national minority’s classic author had to be translated into Russian and other major languages of the USSR. The Georgians had Shota Rustaveli as their classic author, the Ukrainians – Taras Shevchenko, the Belarusians – Yanka Kupala and Yakub Kolas, and the Jews, correspondingly, Sholem Aleichem. Several decades ago, the six-volume collection of his works translated into Russian adorned almost every Jewish home in the USSR.

Streets of many cities in the world, from Birobidzhan to Jerusalem, bear the name of Sholem Aleichem. Even a crater on the planet Mercury was named after him. In some cities of Russia, Israel and Ukraine, monuments were erected in his honor. However, there is still no complete academic edition of his works. Such a publication could by no means appear in the USSR, since quite a few of Sholem Aleichem’s works did not correspond to the Soviet ideological guidelines. One such example is his novel “The Bloody Hoax”, which deals with the blood libel and the lack of legal rights for the Jews in the Russian Empire.

The Soviet citizens were also not supposed to know of Sholem Aleichem’s sympathy for Zionism, of the fact that he participated in two Zionist congresses and wrote a number of journalistic and literary works with explicit Zionist content. However, such a publication, for a number of reasons, has never been produced outside the USSR either, although it would seem that the significance of this writer for Jewish literature is so great that such a project should have started to be undertaken within the century following his death.

Undoubtedly, the compilation of a complete academic collection of Sholem Aleichem’s heritage, which would include all his works, literary, journalistic, and epistolary, some of which were written not only in Yiddish, but also in Russian and Hebrew, would be a difficult task. It would require a large-scale, attentive and painstaking collection of materials. Their publication would also require developing a standardized spelling system. An academic edition would necessarily need to include an apparatus of linguistic, historical and bibliographic commentaries.

An equally important task is to popularize the great writer’s oeuvre, which retains its significance and relevance even now, in the 21st century, despite the fact that the world of the shtetl he describes has now become merely history. In order to popularize such a writer one must thoughtfully create a bridge between his bygone world and the modern realities.

Why do these two tasks need to be put forward, if we wish to immortalize our classic’s legacy? The answer may be found in Sholem Aleichem’s own Testament, where, in particular, he wrote: “For me the best monument would be for my works to be read and for there to be, among the wealthy classes of our people, patrons who wish to publish and disseminate them, both in Yiddish and in other languages… If I did not merit or deserve to have patrons during my lifetime, then – maybe – I will have the merit to have them after death.”