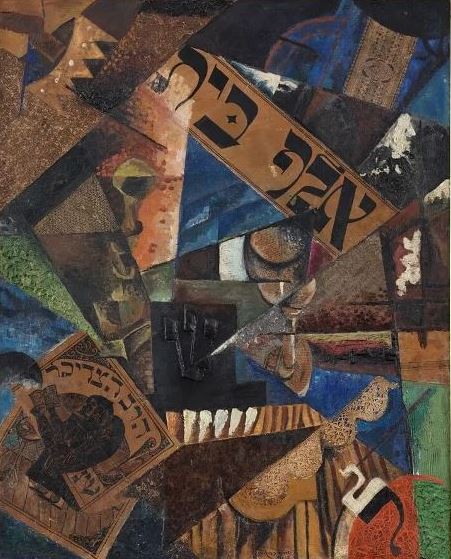

Yiddish and Hebrew

Unlike most other peoples, traditional Jewish communities were for many centuries characterized by internal bilingualism: two languages coexisted in the same community fulfilling different functions. In all Jewish groups, Hebrew was considered the “high” language of sacred texts and worship. As such, it enjoyed high prestige as loshn-koydesh, the holy tongue, as it is called in Yiddish.

For more than a millennium and a half, the Hebrew language was also the main vehicle of “high” literary genres, such as philosophy, theology and mysticism. Modern secular literature, created according to European models of that time, only appeared in Hebrew at the end of the 18th century, as a direct result of the Haskalah, the Jewish version of the European Enlightenment.

At the same time, every Jewish group in its daily life spoke another language, related to the language of the country where they lived or once used to live. However, unlike their non-Jewish neighbors, they would write their vernacular language using the Hebrew alphabet. For a millennium, the vernacular of the Ashkenazi Jews was Yiddish.

Besides being the means of daily communication, it was also the language of their folklore and so-called “low” literary genres. In theory, all Jewish men were expected to master Hebrew at least to some degree for religious purposes. Since women were not obligated to learn the “sacred tongue”, early Yiddish literature often appeared in the guise of supposedly women’s literature.

The Hasidic movement that arose in the first half of the 18th century greatly contributed to the development of Yiddish literature. Appealing to simple and unlearned Jews who were poorly versed in the “sacred” Hebrew, Hasidic leaders spoke in Yiddish, themselves cherished this language as a millennial folk treasure, composed prayers and religious songs in that language. Later, in the early 19th century, the Hasidim even developed theological theories, according to which Yiddish had a sacred or semi-sacred status of its own.

At the same time, the Haskalah had a negative attitude towards Yiddish, considering it a corrupt form of German or a Jewish-German jargon. In Germany, Austria, Czechia, Hungary, this movement succeeded to replace Yiddish by German in the everyday life of most local Jews. However, in Galicia, where the adherents of Haskalah had to confront the Hasidim, they had to take the path of creating their own literature in Yiddish for their propaganda purposes. This led to the creation of a full-fledged modern Yiddish literature, which became an organic part of the modern Jewish literature in general, be it written in Hebrew, Yiddish, Russian or German. Paradoxically, despite their disdain towards Yiddish, the Enlightenment writers created the earliest forms of modern Yiddish literature matching the genres of the major European literary traditions of that time.

Many Jewish writers of the 19th and early 20th century, and occasionally later on, were bilingual. For example, Mendele Moykher-Sforim (1836-1917) and Yitskhok-Leybush Peretz (1852-1915) wrote in both Yiddish and Hebrew. Sholem Aleichem (1859-1915), who became a symbol of Yiddish literature, wrote only some of his works in Hebrew, but still knew the “sacred tongue” very well. Chaim-Nahman Bialik (1873–1934), the classic of modern Hebrew poetry, wrote in Yiddish as well and made an enormous contribution to overcoming the stereotype that Yiddish is a “low language”. Shmuel-Yosef Agnon, the only Hebrew writer so far to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, also wrote some Yiddish stories.

Two mutually exclusive cultural and socio-linguistic ideologies emerged and clashed at the end of the 19th century: Yiddishism and Hebraism. Yiddishism, which placed Yiddish, the language of the daily life of millions of Jews at the center of the Jewish national revival, seemed realistic and pragmatic. Hebraism, on the other hand, offered the seemingly unrealistic and utopian goal of reviving a language that always retained its religious functions, but had not been used in daily conversation for at least fifteen centuries. Fierce disputes between the proponents of these two ideologies were humoristically depicted in Sholem Aleichem’s story “Yiddishists and Hebraists”.

Sholem Aleichem himself was a supporter of the traditional Jewish internal bilingualism. In the preface to the first volume of his works, published in 1911, he wrote the following: “Congratulate me! (…) There are twins in my womb. These twins (…) are our languages, Hebrew and Yiddish. (…) People wage war with their neighbors over them, shed ink like water and waste a lot of paper, ask again and again the most serious question: which of our two languages is more deserving the title of the ‘national language’?”

Sholem Aleichem chooses the third option: “Our people is the strangest of all the peoples in the world. It has been living in exile for two thousand years, cut off from the soil, wandering from country to country and from state to state (…) – and it is fitting for it to have two languages at the same time (…). Thus I believe that we must accept both languages with love.”

However, due to the radicalization of both Yiddishists and Hebraists, this traditional Jewish bilingualism with its organic bilingual and even multilingual creativity, fell apart after the First World War. Yiddish and Hebrew literature departed from each other. In the second half of the 20th century, it became obvious that the Yiddishist model of national revival, which earlier seemed realistic, failed against the once seemingly utopian and now victorious Hebraism.

Yet, modern Israeli Hebrew is so thoroughly influenced by Yiddish in its phonetics, phraseology, syntax and vocabulary that one Israeli linguist, Professor Ghil’ad Zuckermann asserts that the Israeli language, as he calls the modern Israeli Hebrew, is a descendant of two equally involved parents: the original classic Hebrew and Yiddish.

Yiddish itself is thoroughly permeated with words and idioms borrowed from Hebrew and from the closely related Aramaic. Thus, as Sholem Aleichem wrote in the aforementioned preface: “both of these languages borrow treasures from their twin brother.” The prominent American Jewish linguist Uriel Weinreich (1926–1967) even argued, and for good reasons, that “the boundary between Yiddish and Hebrew is not always clear and stable.”

It is certain that none of the other Jewish diasporal vernacular languages of the modern era can be compared with Yiddish in its influence on Jewish culture in general, including the modern Hebrew. Perhaps, the degree of influence of Yiddish on Jewish culture can be compared to that of Aramaic, which was the main Jewish vernacular from the late antiquity till the early Middle Ages, and remains the main language of Talmudic literature.