Evgeny Kissin: Music

Evgeny Kissin: Short Biography

Evgeny Kissin: Short Biography

Evgeny Kissin (born in 1971) is an outstanding pianist, one of the greatest contemporary music performers who became famous as an internationally renowned star at the age of 12, when he performed two of Chopin’s piano concertos in one evening.

When the young musician was a child in Moscow, his parents gave him a calendar card with the Hebrew alphabet, which they bought in a second-hand bookstore. Kissin quickly learned the letters, but at first did not find any use for them.

In 1977, the composer and theater director Yuri Sherling (born in 1944) created the Chamber Jewish Musical Theater, which performed in Yiddish and Russian. This was an unexpected event in the country, where the very word “Jew” was often a taboo subject. The first performance of this theater, the musical The Black Bridle of the White Mare, was staged by Sherling in two languages and was written by two well known poets: Chaim Beider (the Yiddish version) and Ilya Reznik (the Russian one). When the cover of this work’s vinyl record, which contained both versions of the libretto, reached Kissin who always had a phenomenal memory, he used it as a textbook of sorts for learning Yiddish.

In 1989, the Kissin family emigrated to the West. The young pianist started his intensive international concert activities. At some point, he began to appear on stage not only as a musician, but also as a reciter of Yiddish poetry. The regular participants of prestigious music festivals did not expect the world-famous star to recite poetry in a language that was only understood by very few people. It did not fit into the stereotypical view that this musician only focuses on piano performances.

An important event in Kissin’s life was his acquaintance with Boris Sandler, one of the few living speakers of Yiddish of the older generation whose long professional career as a writer and journalist is linked to this language.

Evgeny Kissin’s participation in the development of contemporary Yiddish culture has three aspects. First, he still appears on the stage with programs that are directly related to this language. As a recent example, he performed at the Carnegie Hall together with the artist Veniamin Smekhov at an event dedicated to the 70th anniversary of the execution of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC). Second, he has already published two of his own Yiddish books, where he appears as a writer, poet and translator. Third, his musical and literary activities were combined in his own chamber and theatrical music compositions. In 2019, Birobidzhan hosted the premiere of the children’s musical fairy tale play The Bird Alef From the Old Gramophone, written in Yiddish by Boris Sandler. The music was written by Evgeny Kissin. The 2022 play called Gramophone, made by the same creative duet and staged in Prague, is dedicated to the Holocaust memory.

Music

Music

Moisey Beregovsky

Lev (Leib) Pulver

Dmitry Shostakovich

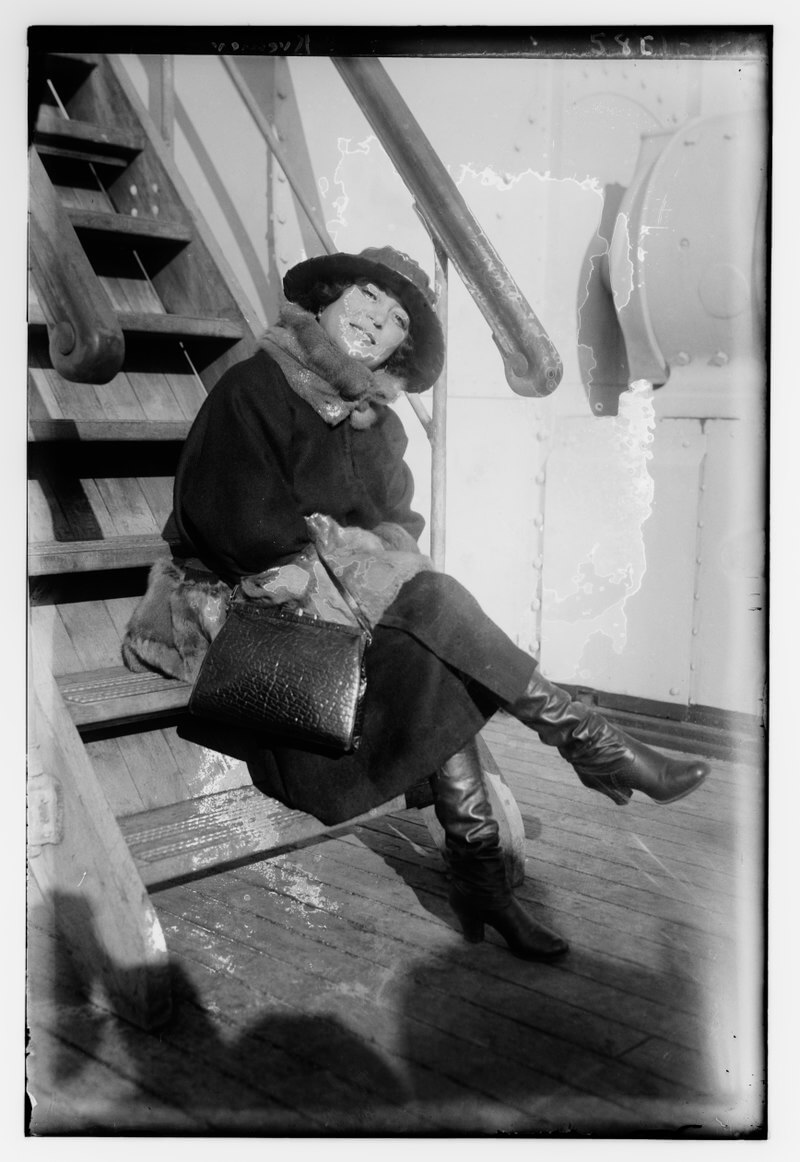

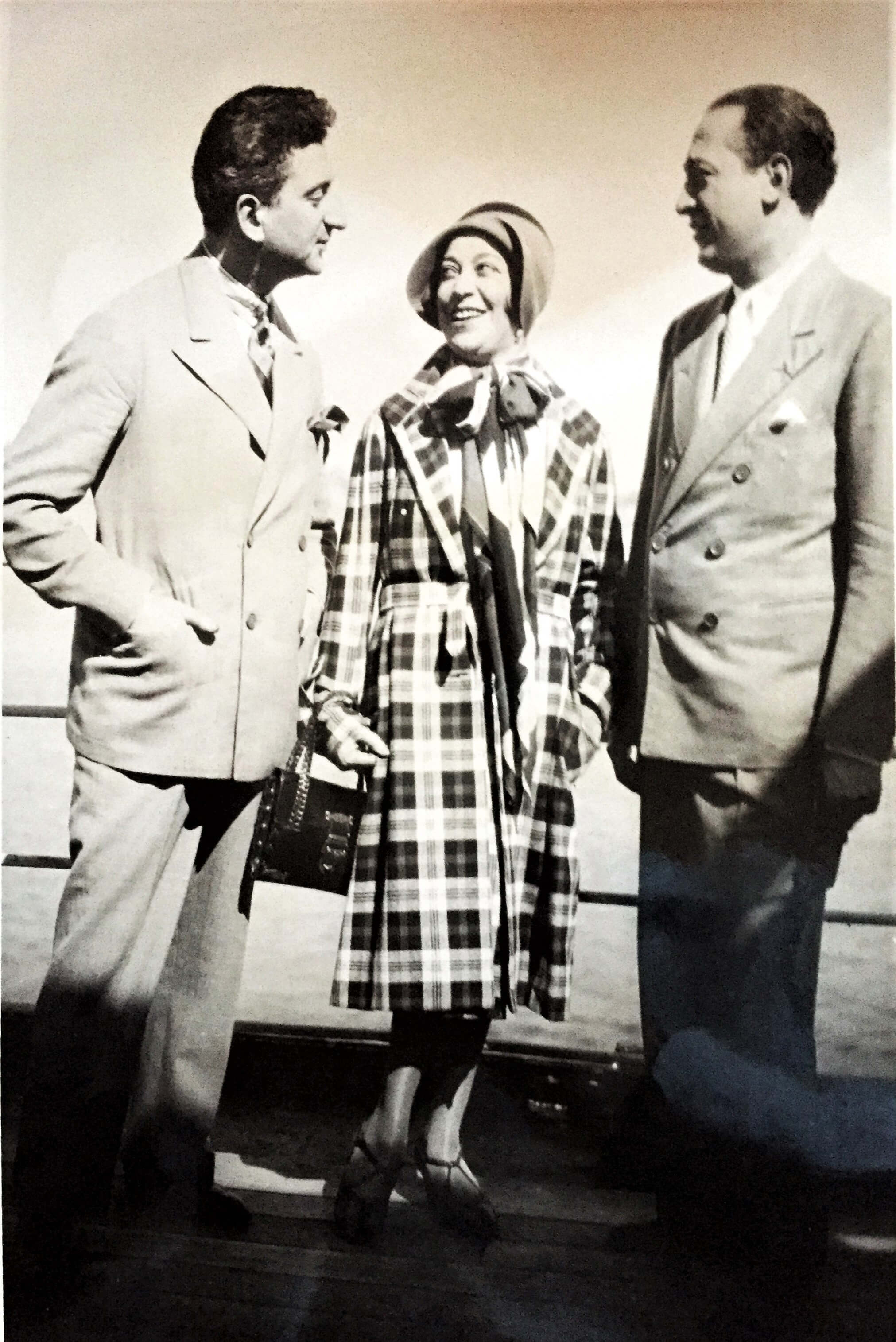

Isa Kremer

Nechama Lifshitz

Sidi Tal

Klezmer music

Imagine some shtetl in the mid-18th or early 19th century, somewhere in Ukraine or Belarus, Poland or Lithuania. A Jewish mother sings a lullaby to her baby, and the baby already begins to understand and memorize some Yiddish words. The language, native to this child, is going to become the instrument of his or her speech, thought, comprehension of everything in the world.

Who is the author of this lullaby, of its melody? Who blended the words and the melody together, and when? We will probably never know, but these songs have reached us after passing from generation to generation.

The Jewish folk musicians – the Klezmers – would play the same melodies without the lyrics at weddings and other celebrations. They would memorize them without knowing any notes. Much later, in the early 20th century, such extraordinary people as Moisey Beregovsky would spend years and even decades traveling from town to town, in order to record and then publish these melodies, to preserve the priceless musical heritage of the Jewish people tormented by pogroms and all sorts of hardships.

Before Beregovsky, right before the beginning of the 20th century, the Jewish theater – meaning the Yiddish theater – was born in Eastern Europe. Some of its creators emigrated to America and became founders and performers of dozens of theaters, where the actors would also play in Yiddish.

Another important figure to appear along with the actors and theater directors was the composer. Inevitably, the composer would be the co-director of the performances, unimaginable without their musical aspect. In fact, early musical folk performances were the forerunners of professional Broadway musicals.

Lev (Leib) Pulver was a truly universal Soviet composer who created the music for almost all the performances of the Moscow State Jewish Theatre (GOSET). Among professional performers of Yiddish songs in different countries, Isa Kremer was certainly one of the brightest stars. Still, the music associated with the Yiddish culture had to make another round in order to become an integral part of the world classics.

When Stalin and his associates, after having brutally murdered Solomon Mikhoels, one of the leaders of the Soviet Jewish intelligentsia, were preparing to kill the best Jewish poets and writers, the brilliant Russian composer Dmitry Shostakovich managed to introduce elements of Yiddish folk music into his own musical language.

Shostakovich wrote vocal and instrumental music that expresses an extreme degree of tragedy, using the tonality of Jewish folk melodies. As a great artist, he felt that this purely instrumental wordless music reflects the emotions of its unknown authors better than any words. This ingenious, universally recognized music is rooted in the traditional Yiddish culture.

In the second half of the 20th century, the Broadway musical “Fiddler on the Roof” thundered across the world as a masterpiece of its genre. It shows that the characters of Sholem Aleichem’s works, who originally spoke Yiddish, can win the hearts of people even in our modern times of space travel and computer technologies. By this example, the Yiddish culture has been proven to be not archaic, but both modern and eternal. Klezmer music is also thriving today and attracts thousands of fans at festivals and concerts all across the globe.

Klezmer Music

Klezmer Music

Yiddish Glory:

Resurrecting archives of Jewish history

Psoy Korolenko &

All Stars Klezmer Band

Today’s Yiddish culture experiences a multi-faceted reemergence of its classic manifestations deemed by many, until recently, dying or already gone without a slightest hope of revival. One example of this process is the ongoing development of klezmer music that began about five decades ago.

By the middle of the 20th century, the original Eastern European tradition of the Ashkenazi folk music practically had come to an end. Yet, during the 1960s and 1970s, its revival began in the USA and Canada. By the late 1970s, klezmer music became a widespread North American genre, popular not only among Jews. It should be noted that this was the time when world music in general came into fashion. While relying on surviving musical notes and especially sound recordings, the postwar generation of klezmer musicians, being a part of this wave, were striving to reproduce the original 19th century folk style as authentic as possible.

Among the most prominent pioneers of this revival were Michael (Meyshke) Alpert and Walter Zev Feldman; both were born in the USA in the 1950s. Moisey (Moyshe) Beregovsky’s monumental collection of Jewish instrumental folk music, published in Russian (1987) and in English (2001), provided a significant stimulus for the growing popularity of klezmer compositions.

The old klezmer music was primarily created to accompany dancing. Its subgenres were named after Jewish folk dances: freylekhs, sher, hora, zhok, skochna, bulgar, etc. Naturally, this also led to the revival of traditional Jewish folk dances, alhough their authentic reproduction turned out to be a rather difficult task; until recently, choreography remained a poorly researched subject within Jewish folklore studies.

During the 1990s, klezmer music became simultaneously fashionable in North America, Western Europe and post-Soviet countries. Western European festivals of ethnic music would typically include klezmer performances. At the same time, a tradition of Klezfest festivals had emerged, dedicated specifically to Jewish folk music. In both North America and Europe such events attracted Jews and non-Jews alike among its audience, as well as among performers.

The development of klezmer music in Israel took a different route. The old musical tradition of this country was not completely broken, but the local klezmer music mainly dissolved into what is commonly known in Israel as “Hasidic music”, performed at weddings and such massively crowded religious festivities as the celebrations of Lag B’Omer on Mount Meron, near the grave of the famous Talmudic sage and mystic Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai. However, it remained outside the Israeli mainstream culture.

Musa Berlin, born in Tel Aviv in 1938, made a great contribution to the popularization of klezmer music in Israel. In particular, he was the first to draw attention to the unique musical tradition of the Palestinian klezmers, which developed among the descendants of Ashkenazi Jews who settled in the historical Land of Israel during the late 18th and early 19th century. One characteristic feature of the Palestinian klezmer music is a noticeable Oriental influence stemming from Arabs and non-Ashkenazi Jews.

A very influental figure on the Israeli klezmer scene is the clarinetist Giora Feidman. Born in 1936 in Argentina, he immigrated to Israel in 1957. Besides his successful career as a performer of classical music, he showed a great interest in klezmer melodies. His first solo album “Freylekhs and Hasidic Melodies”, released in 1971, became a landmark for klezmer fans all over the world. Unlike the American musicians who strove to reproduce the authentic styles based on the records from the 19th and early 20th century, Feidman turned the old folk melodies into classical performances.

Despite these early developments, “real” klezmer bands in Israel began to appear only in the early 2000s. In 2003, Gershon Leizerson, a Russian-born student of the Buchmann-Mehta School of Music, who had immigrated to Israel with his parents in the early 1990s, created the klezmer band called Nigun Hadash. Three years later, when he performed at the Canadian Klezfest, he found surprising that the revived klezmer tradition in Western countries was so extremely popular and rich.

After returning to Israel, Leizerson created the ensemble Oy Division together with Asaf Talmudi (born in Israel in 1976), which successfully performed klezmer music and Yiddish songs in Israel and elsewhere. In 2008, this band carried out several joint projects with the Russian-American singer and songwriter Psoy Korolenko (Pavel Lion, born in 1967 in Moscow) who uses Jewish folk melodies and Yiddish texts for his own songs, often combining Yiddish, Russian, French and English.

Such collaborative projects illustrate new trends in modern klezmer music that deliberately deviate from the conventional “authentic” approach. Leizerson insists that music should live, develop and not remain merely a monument of the past. The popular American performer Daniel Kahn (born in 1978 in Detroit) is another successful proponent of this view. In Berlin, where he currently lives, he created the band Painted Bird, which plays non-traditional klezmer music, often mixing Yiddish, English and German. Like Korolenko, Kahn has carried out a number of joint projects with Oy Division. In 2017, Gershon Leizerson founded the Jerusalem-based Israel Klezmer Orchestra.

(To be continued)