Exhibits and Performances

Yevgeniy Fiks: Short Biography

Yevgeniy Fiks: Short Biography

Yevgeniy Fiks is an artist and exhibition organizer, who developed the concept of Yiddish Cosmos and wrote an artistic manifesto on contemporary Yiddish art.

Born in 1972 in Moscow, he has been living and working in New York since 1994.

Yevgeniy Fiks

In the early 1980s, Fiks became interested in Yiddish, which he had heard from birth, and asked his grandmother to teach him this language. Later, while living in America, Fiks created his own concept of Yiddish as a “cosmic” language, capable of connecting heaven and earth, everyday life and fantastic utopia, Jewish and global culture. In 2018, his exhibition Yiddish Cosmos was held for the first time in New York and later on took place in his hometown, Moscow.

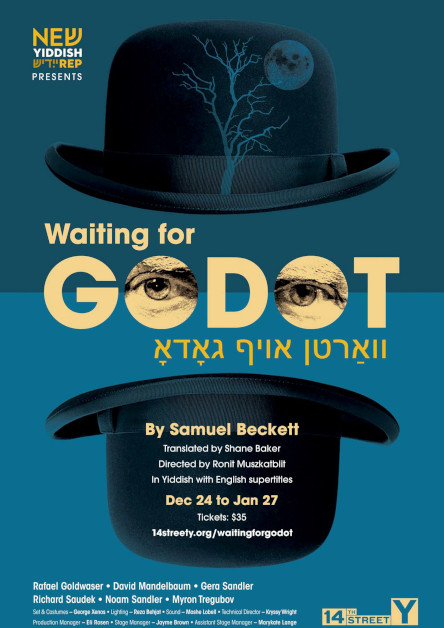

In his artistic manifesto, Fiks reflects on the growing popularity of Yiddish among the younger generation of artists, writers and scientists, on the special place of this language in contemporary avant-garde art. Among other examples, he cites the work of the Afro-American Yiddishist Anthony Russell and the Yiddish translation of the play Waiting for Godot by the Irish classic Samuel Beckett. The artist emphasizes the uniqueness of Yiddish culture as a bridge capable of uniting traditional ethnicity with universal human ideals, the past with the present and the “cosmic” future.

In 2022, the famous Venice Biennale, one of the largest international art exhibitions, opened the Yiddishland Pavilion. The curators of this exhibit are Yevgeniy Fiks and Maria Veits.

The Bird Alef From the Old Gramophone

The Bird Alef

From the Old Grammophone

Song lyrics and libretto by Boris Sandler

Music by Evgeny Kissin

Evgeny Kissin: Music

Evgeny Kissin: Music

Evgeny Kissin: Short Biography

Evgeny Kissin: Short Biography

Evgeny Kissin (born in 1971) is an outstanding pianist, one of the greatest contemporary music performers who became famous as an internationally renowned star at the age of 12, when he performed two of Chopin’s piano concertos in one evening.

When the young musician was a child in Moscow, his parents gave him a calendar card with the Hebrew alphabet, which they bought in a second-hand bookstore. Kissin quickly learned the letters, but at first did not find any use for them.

In 1977, the composer and theater director Yuri Sherling (born in 1944) created the Chamber Jewish Musical Theater, which performed in Yiddish and Russian. This was an unexpected event in the country, where the very word “Jew” was often a taboo subject. The first performance of this theater, the musical The Black Bridle of the White Mare, was staged by Sherling in two languages and was written by two well known poets: Chaim Beider (the Yiddish version) and Ilya Reznik (the Russian one). When the cover of this work’s vinyl record, which contained both versions of the libretto, reached Kissin who always had a phenomenal memory, he used it as a textbook of sorts for learning Yiddish.

In 1989, the Kissin family emigrated to the West. The young pianist started his intensive international concert activities. At some point, he began to appear on stage not only as a musician, but also as a reciter of Yiddish poetry. The regular participants of prestigious music festivals did not expect the world-famous star to recite poetry in a language that was only understood by very few people. It did not fit into the stereotypical view that this musician only focuses on piano performances.

An important event in Kissin’s life was his acquaintance with Boris Sandler, one of the few living speakers of Yiddish of the older generation whose long professional career as a writer and journalist is linked to this language.

Evgeny Kissin’s participation in the development of contemporary Yiddish culture has three aspects. First, he still appears on the stage with programs that are directly related to this language. As a recent example, he performed at the Carnegie Hall together with the artist Veniamin Smekhov at an event dedicated to the 70th anniversary of the execution of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC). Second, he has already published two of his own Yiddish books, where he appears as a writer, poet and translator. Third, his musical and literary activities were combined in his own chamber and theatrical music compositions. In 2019, Birobidzhan hosted the premiere of the children’s musical fairy tale play The Bird Alef From the Old Gramophone, written in Yiddish by Boris Sandler. The music was written by Evgeny Kissin. The 2022 play called Gramophone, made by the same creative duet and staged in Prague, is dedicated to the Holocaust memory.

Evgeny Binevich

Evgeny Binevich:

Book and Its Author

The way this book was created and what happened many years after its publication is somewhat unusual.

More than ten years ago, my Soviet-born friend Alexander Dranov who has been living in the US since the 1970s and works as a lawyer, called me and asked me to help him publish a book about the history of Jewish theater in Russia.

Alexander himself, although he chose a law career, always was unusually artistically inclined his life, which may have to do with genetics: both of his grandfathers and grandmothers were famous Jewish actors who had shining, albeit difficult lives and stage careers.

Evgeny Binevich

Of course, neither he nor I could have possibly known them. However, I very well knew Alexandrov Dranov’s mother: Rosa Kurtz, the former actress of Solomon Mikhoels’ Moscow State Jewish Theater (GOSET) who went through severe hardships in her life. After the theater’s closure, she had to take care of her chronically ill husband who was confined to bed and then had to wander across faraway Soviet places with Vladimir Shvartser’s troupe; he created the Jewish Theater Ensemble on the ruins of GOSET.

She then emigrated to the US. I was impressed by the huge cover article in a Houston newspaper (it is where the Dranov family had emigrated from Soviet Russia) with the large title “Jewish Theater Comes to Houston”. This was an enthusiastic review of Rosa Kurtz’s solo performance with excerpts from plays and songs in Yiddish.

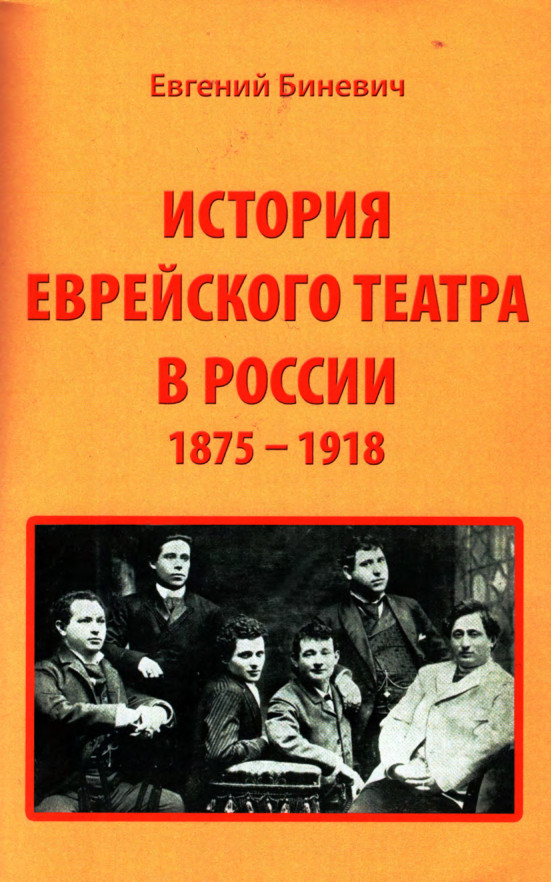

This time it was a different matter though. Alexander Dranov told me that he was contacted by Evgeny Binevich, a well known theater critic who lived in Saint Petersburg, Russia, and was writing at that time a profound monograph on the history of Russian Jewish theater. Binevich gave Dranov access to his entire extremely rich family archive. Knowing that I was already a publisher at that time, my friend appeal to me and I helped him to release the book.

For a very long while I did not think of this story and then, a year ago, I was unable to fall to sleep after returning to America and took a random book from the shelf to entertain myself. That was Evgeny Binevich’s “History of Jewish Theater in Russia: 1875-1918”. I opened it, read Alexander Dranov’s grateful autograph on the back cover and paged through the selection of numerous archival photographs in the final part.

Precisely at that time, I was starting to develop my project for the preservation of Yiddish culture. The theme of the book I’ve randomly opened was directly related to it. The next morning I called Dranov. At that time, I had not been in contact with him for a long while. The very next day we were dining at one of New York restaurants. After the usual quick words of politeness, I told him about my project and turned to questions that interested me very much.

It turned out that he still had his family archive safe and intact. Moreover, after his mother’s death he unexpectedly discovered her hitherto unknown and, obviously, unpublished memoirs. I could barely hide my excitement and joy when he said that all rights to Binevich’s book belong only to him and to the author, and that he conveys those rights together with the memoirs of his mother, Rosa Kurtz, with his preface for the first publication on this website dedicated to my project.

But that is not the end of the story.

Returning home from the dinner, I opened the address book on my phone and found Evgeny Binevich. Fortunately, I never delete any numbers once entered.

When I dialed the number, I heard a woman’s voice. That was the author’s daughter Valeria who said that her father passed away two years ago. It turned out that she had heard about me from her father, who, according to her, was grateful to me for helping him to publish the book. Then she asked me if I was going to St. Petersburg, because her father left a huge archive and she did not know what to do with it.

A few months later, I went to St. Petersburg and visited Valeria Binevich. When she found out that I intended to place her father’s book as one the first and most important materials on this new website dedicated to Yiddish culture (see the Theater section), she said that she would give me her father’s entire archive for my work, free of charge. This was an invaluable gift, which will undoubtedly help to perpetuate the memory of this true knight of art and, specifically, of the Jewish theater.

Together with the archive, Valeria gave me a tiny brochure with a more than modest title: “Evgeny Binevich. Bibliography”. A formal list of his published works, as befits a bibliographic reference, ended with a brief but incredibly poignant autobiographical sketch. Here I am quoting a few excerpts from it. The last lines are especially heartbreaking.

“… The life is ending… Will there be enough time to publish anything else? This little brochure, at least?

… Basically, spent the life in humiliating poverty. We did not go hungry, we did not walk around in rags… But even buying my wife a flower or mailing abroad our next publication was always a problem. And we could not afford to have a second child.

… And yet now, near the end, it often occurs to me that I have lived a happy life … I did not write a single opportunistic line. I only wrote about things that I myself was interested in… “

Mark Zilberquit