Fine Arts

Fine Arts

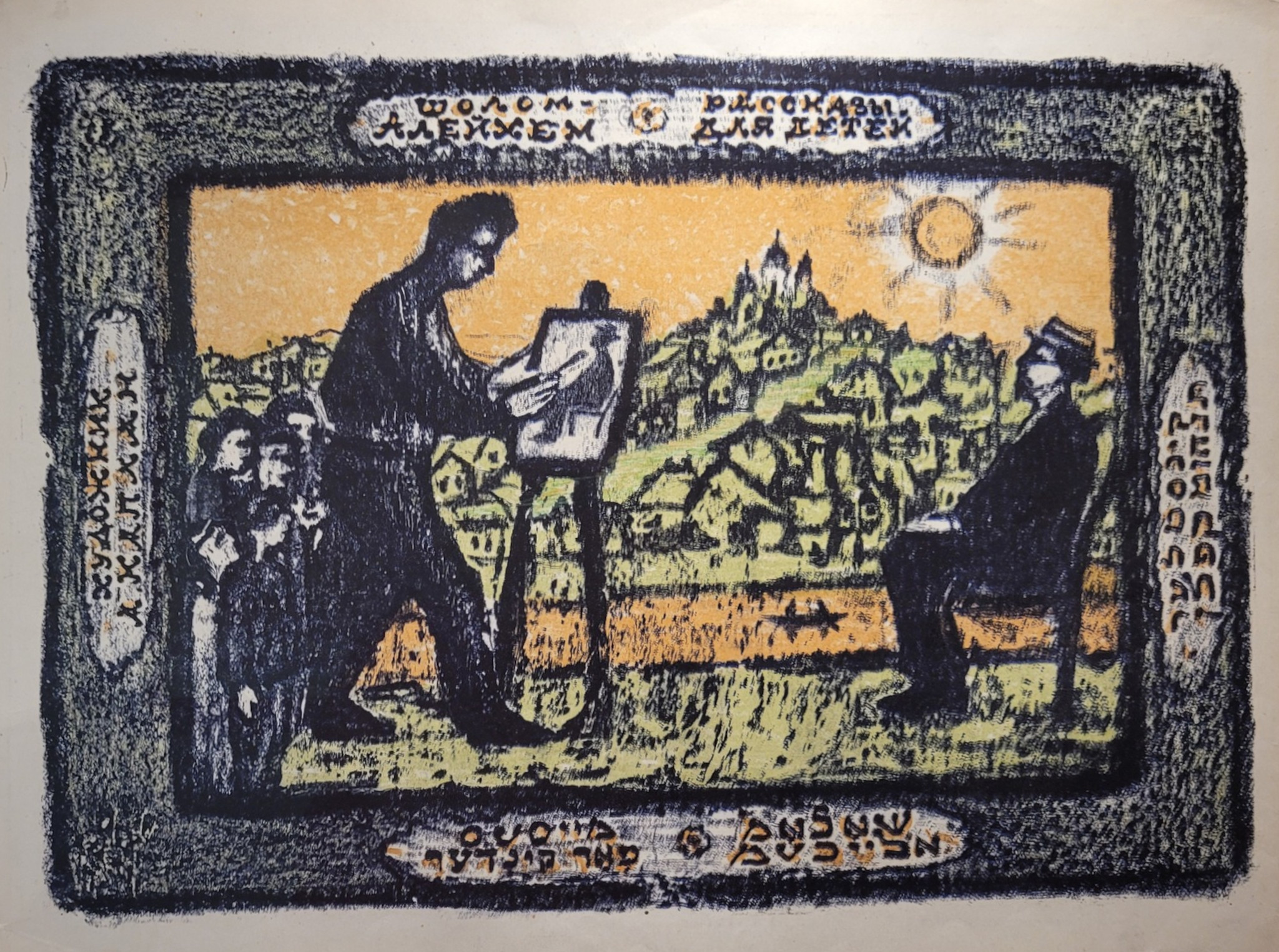

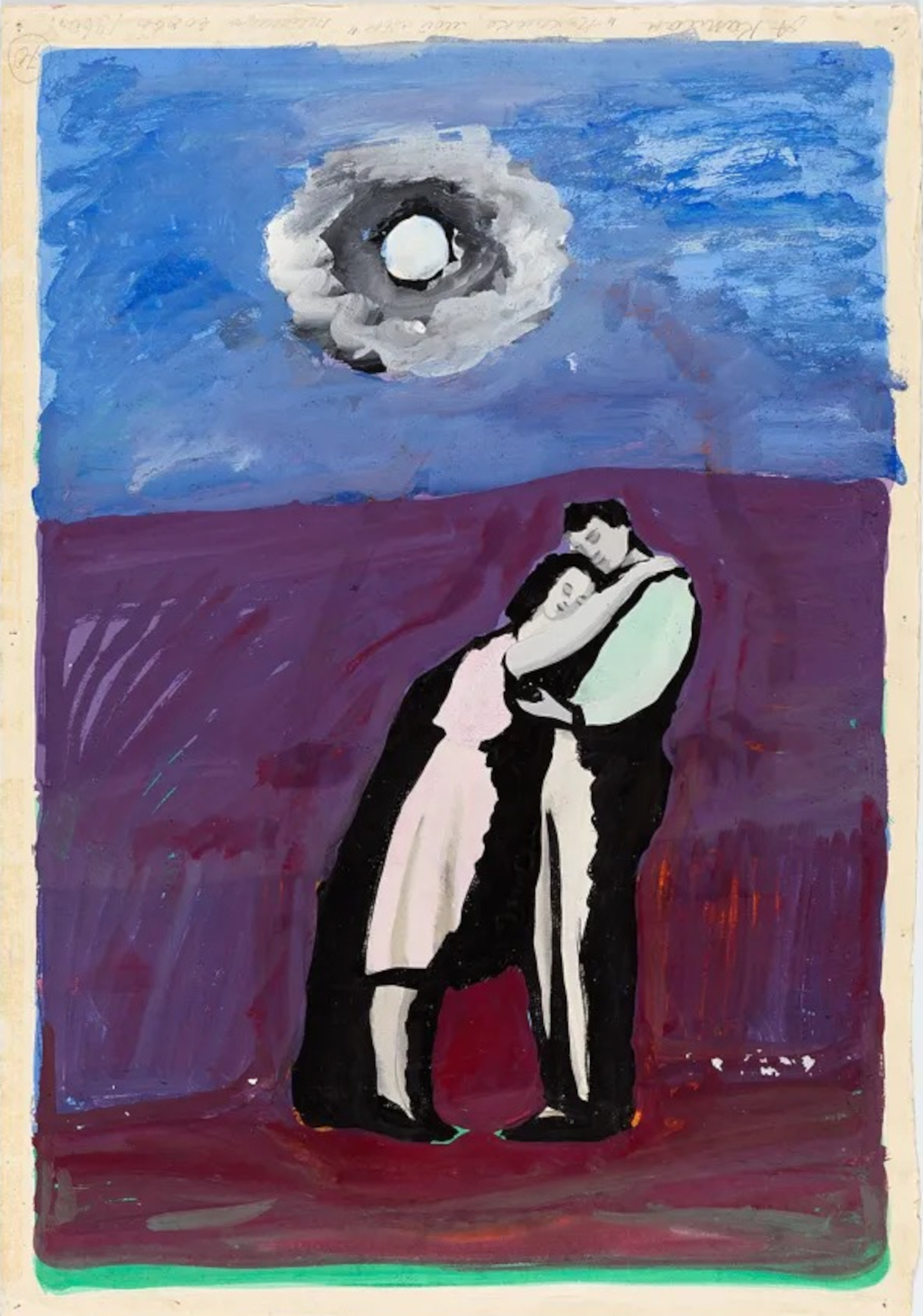

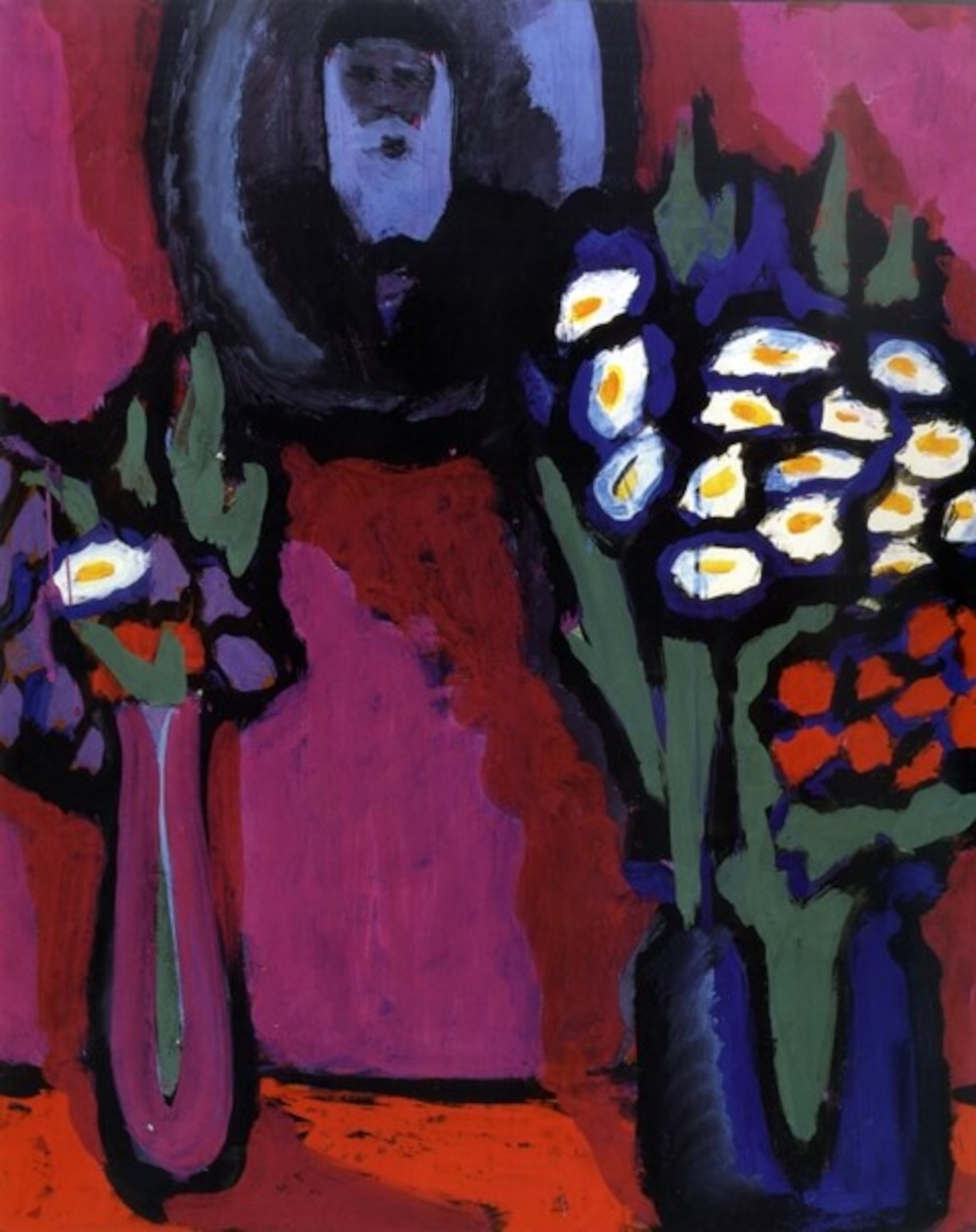

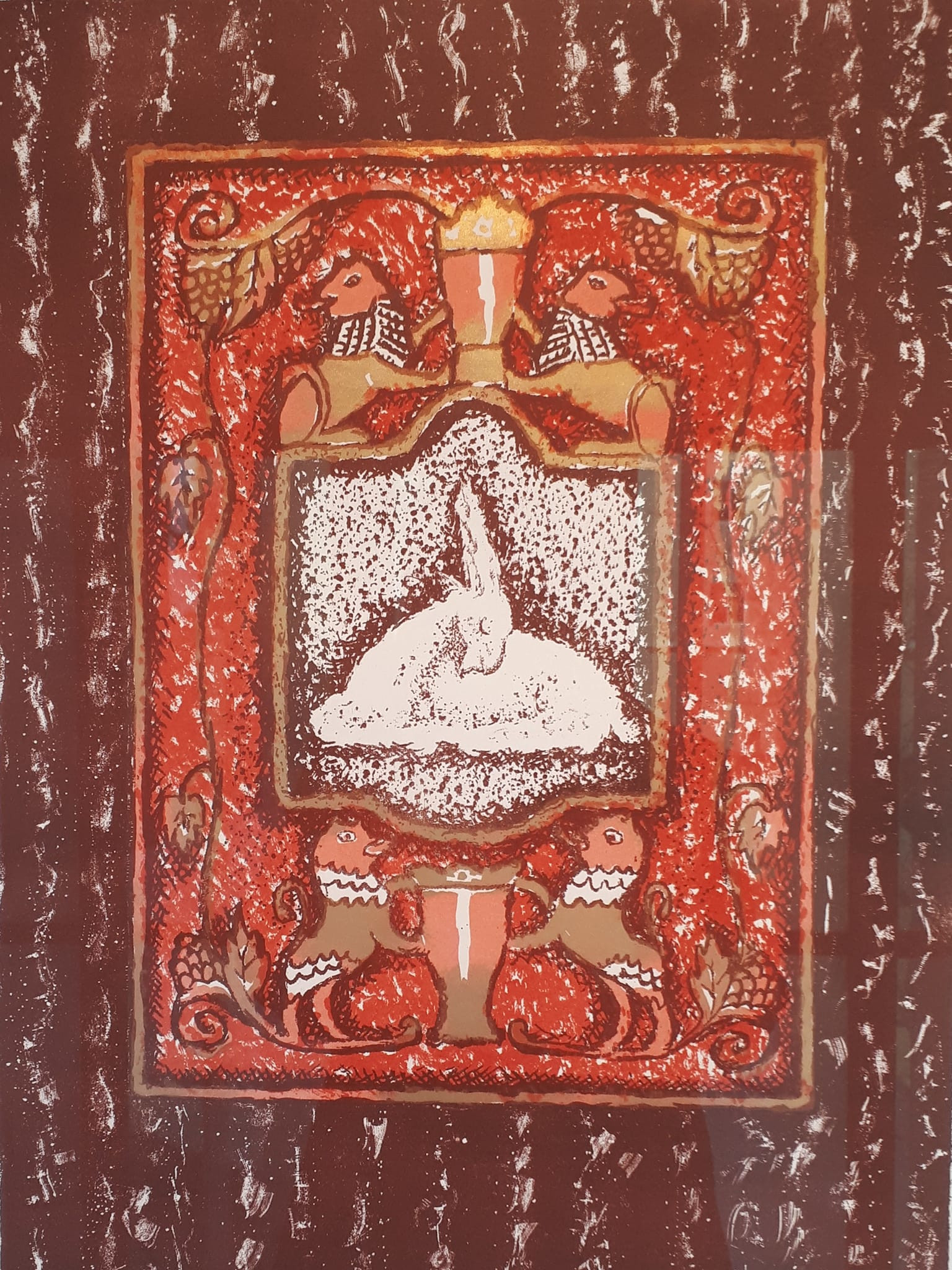

Mark Chagall

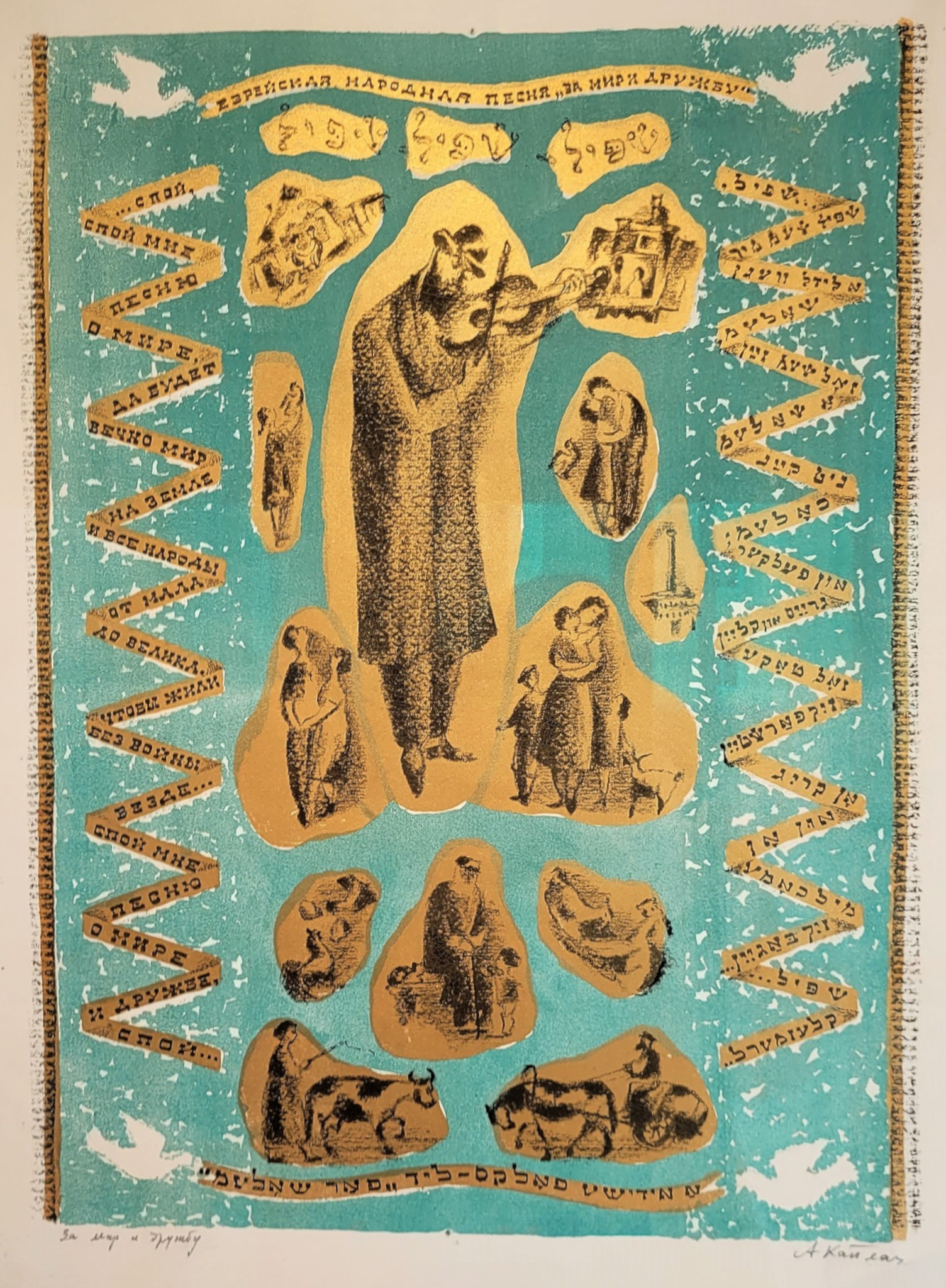

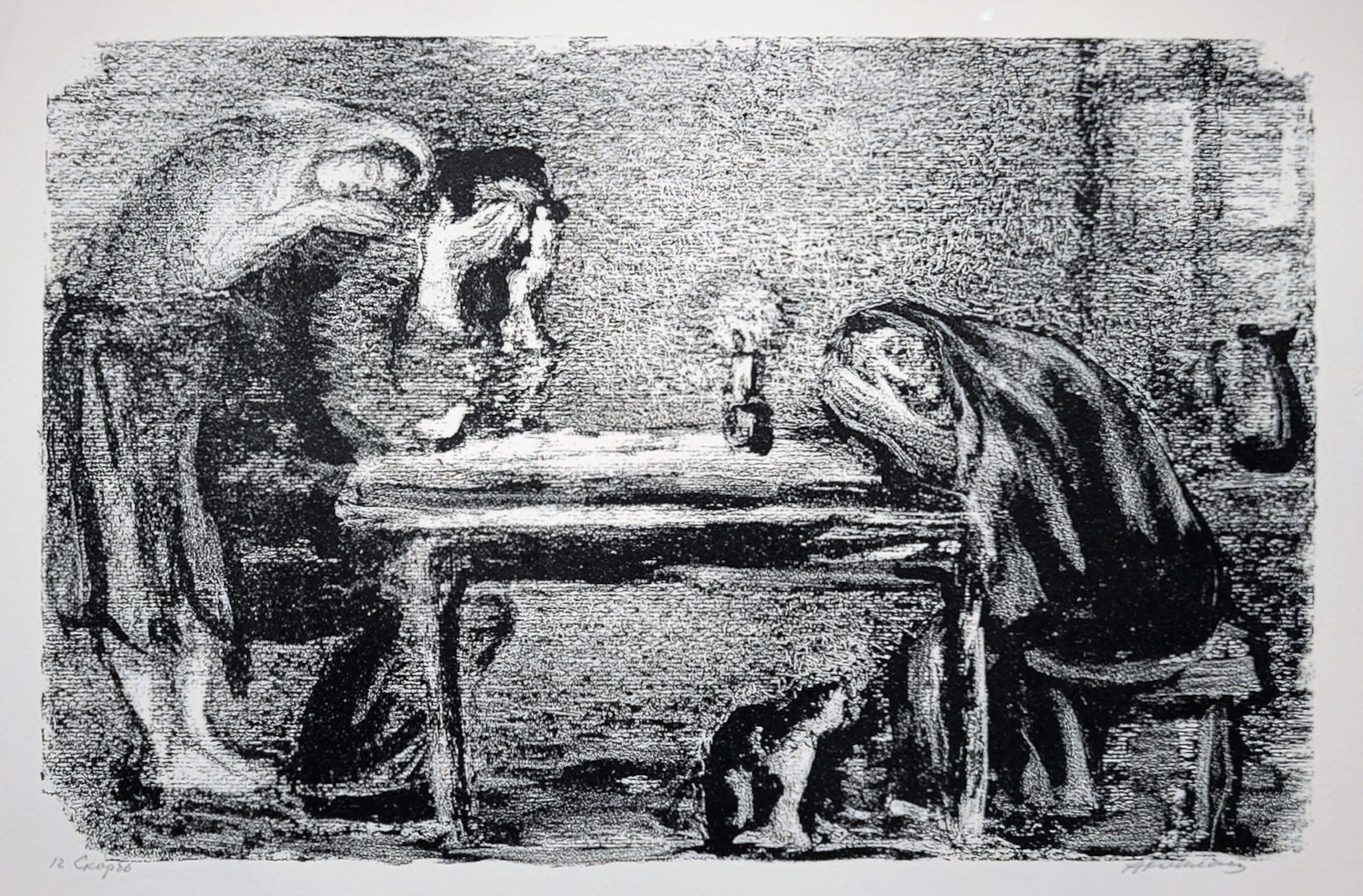

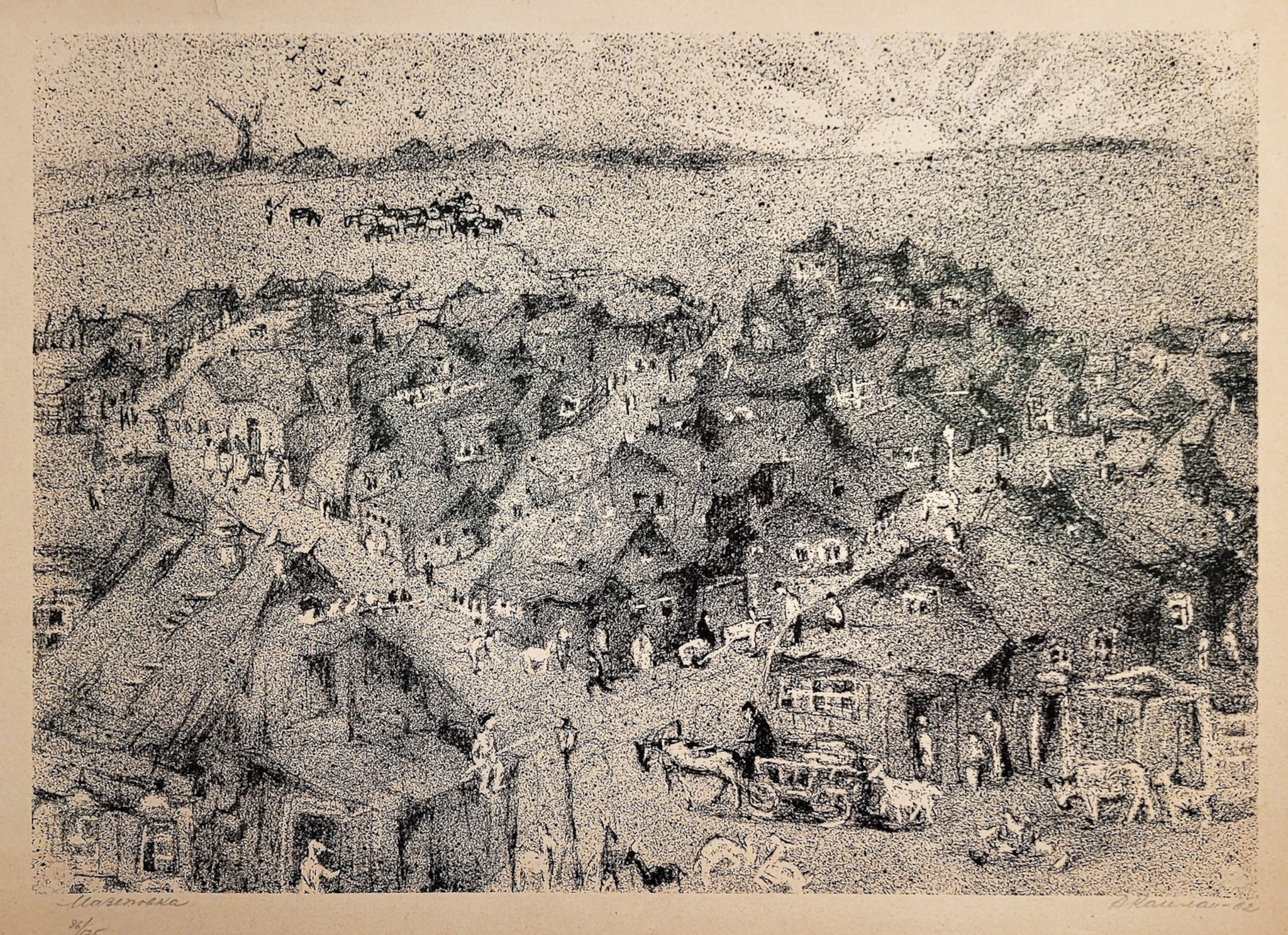

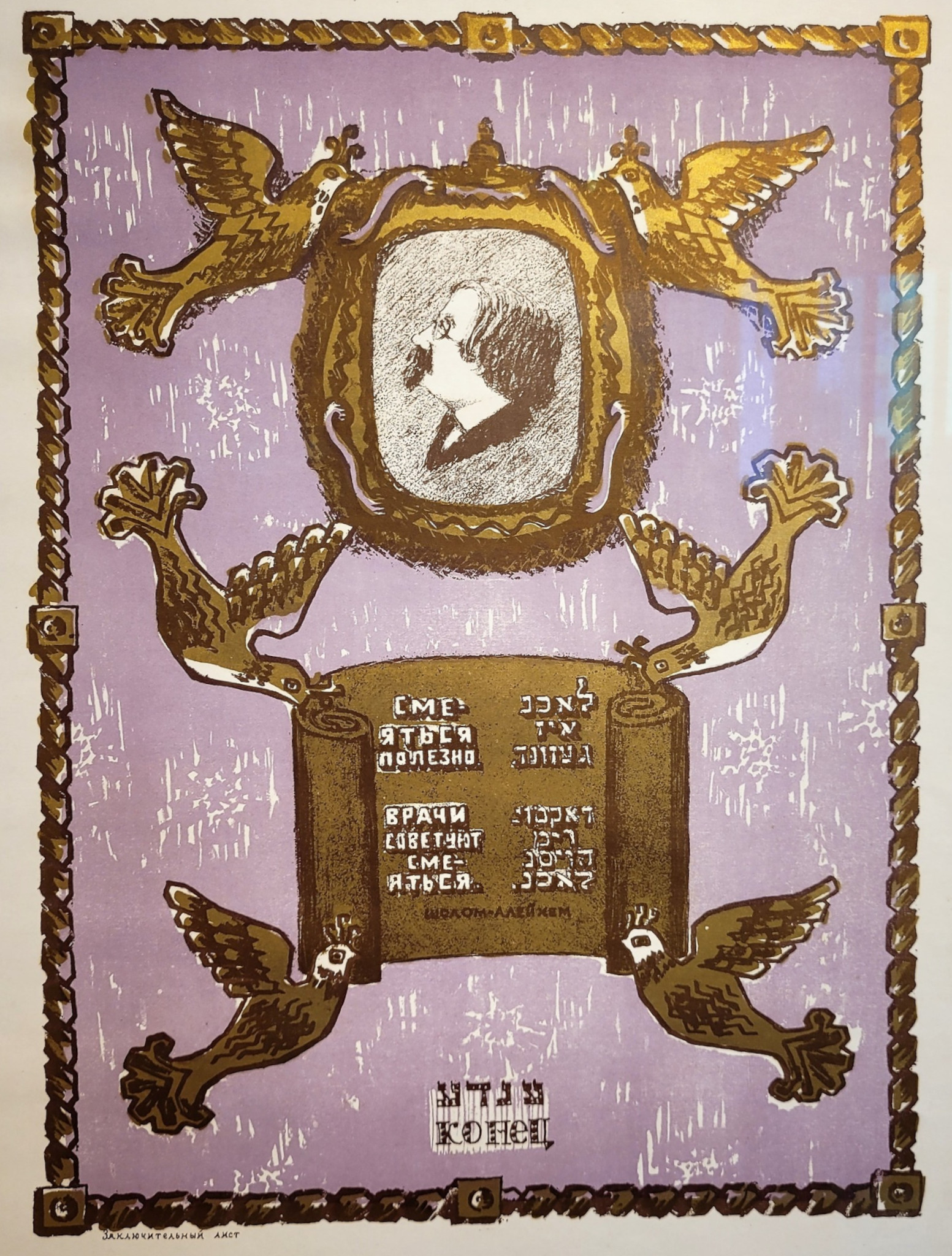

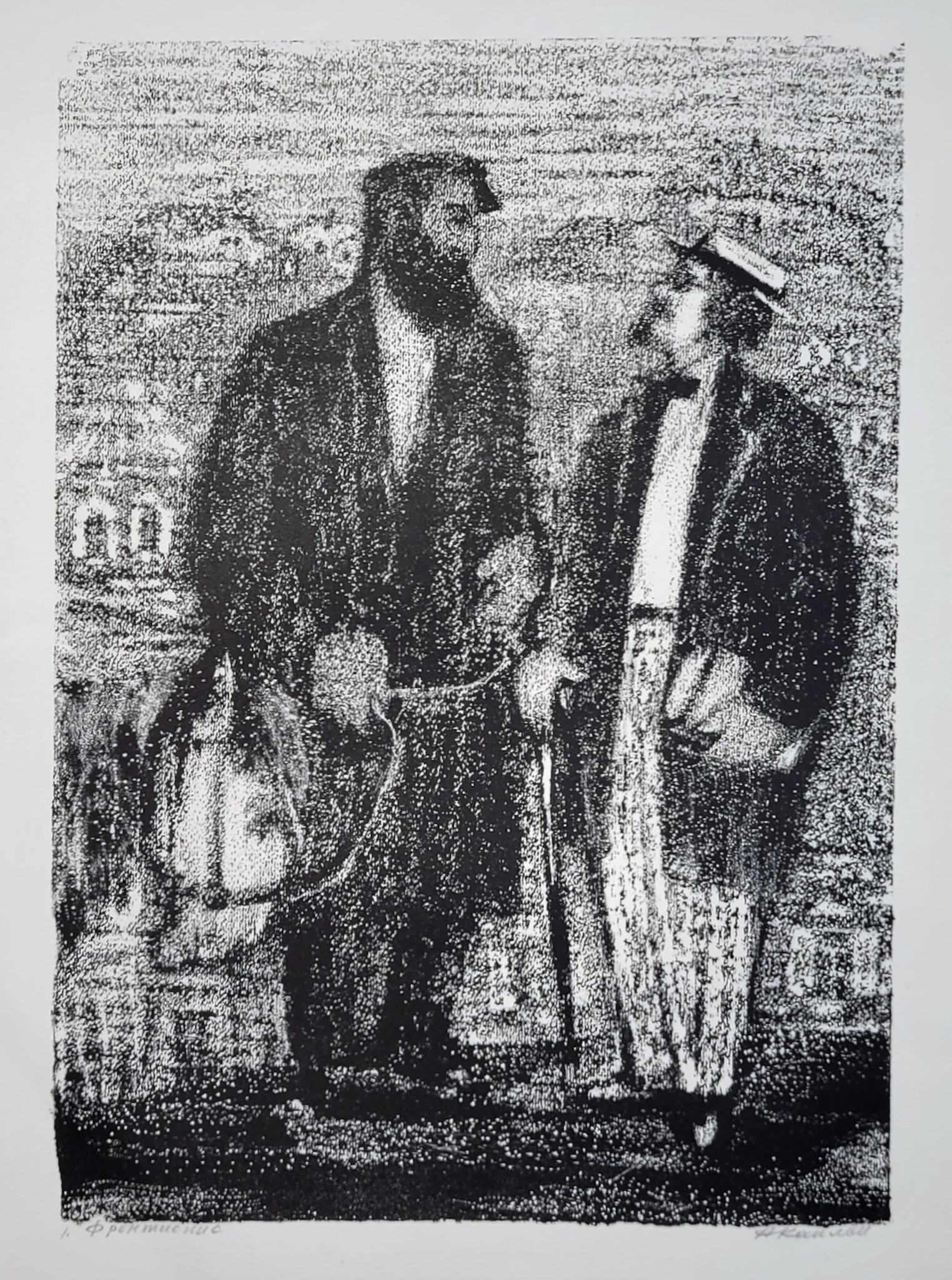

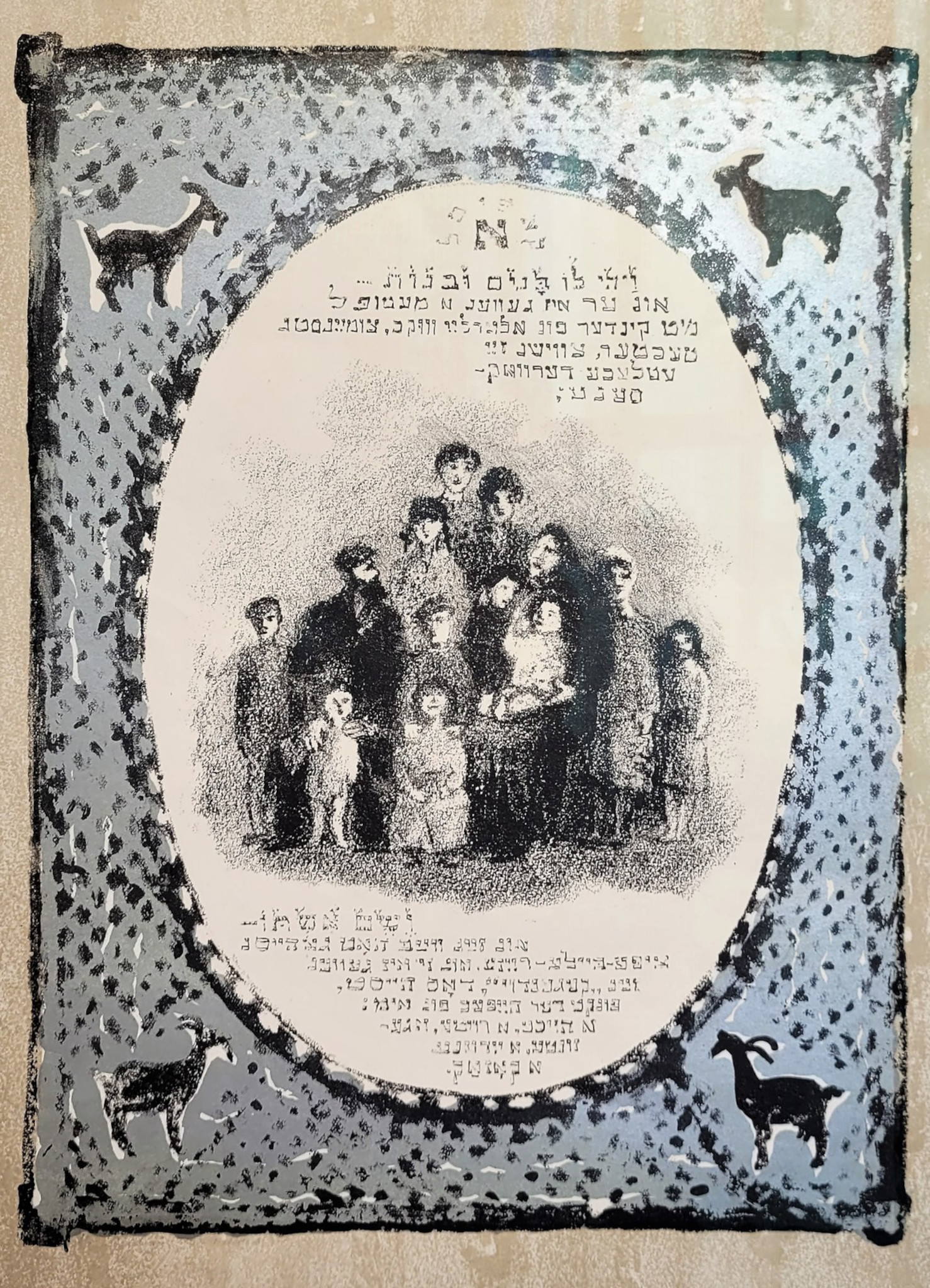

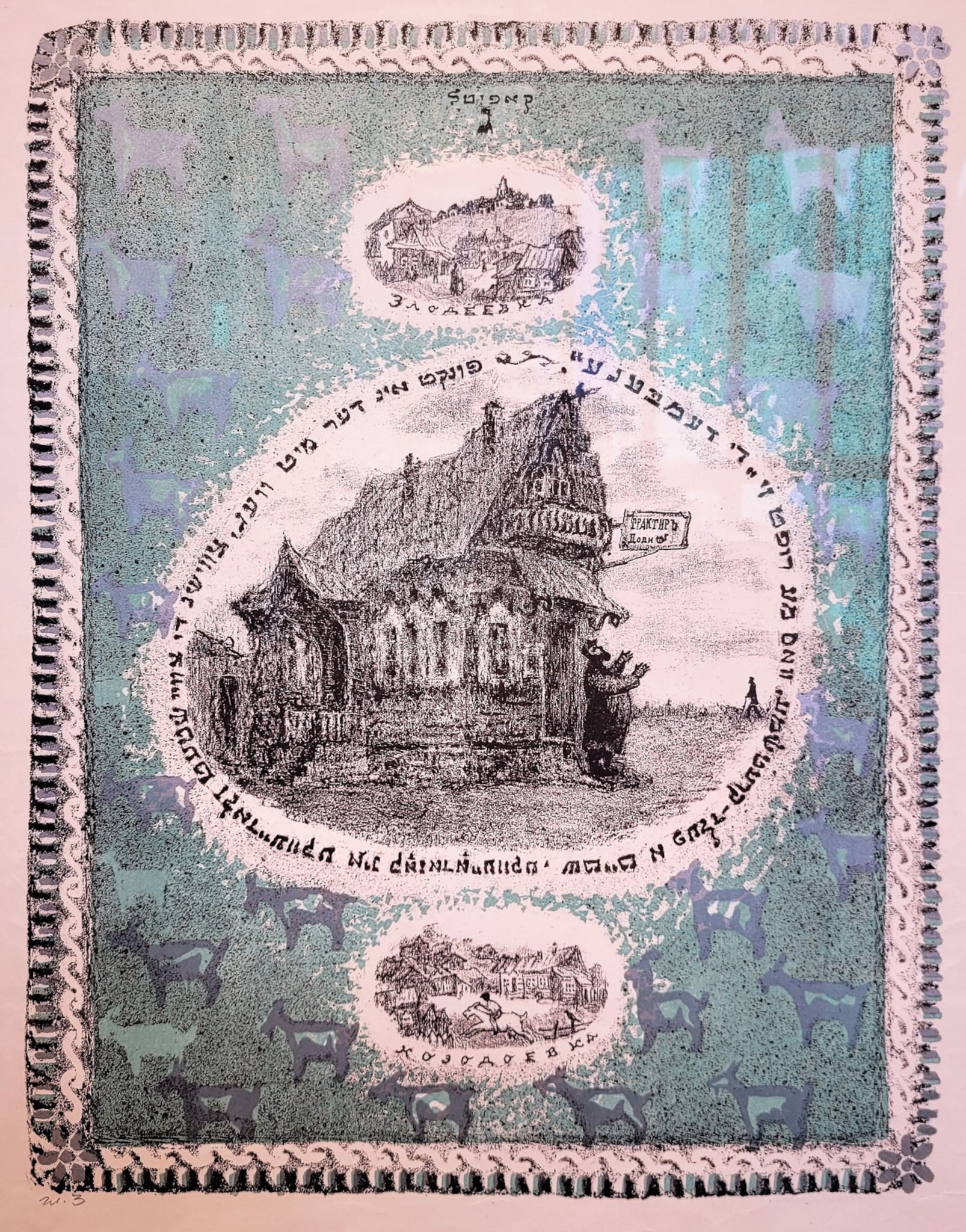

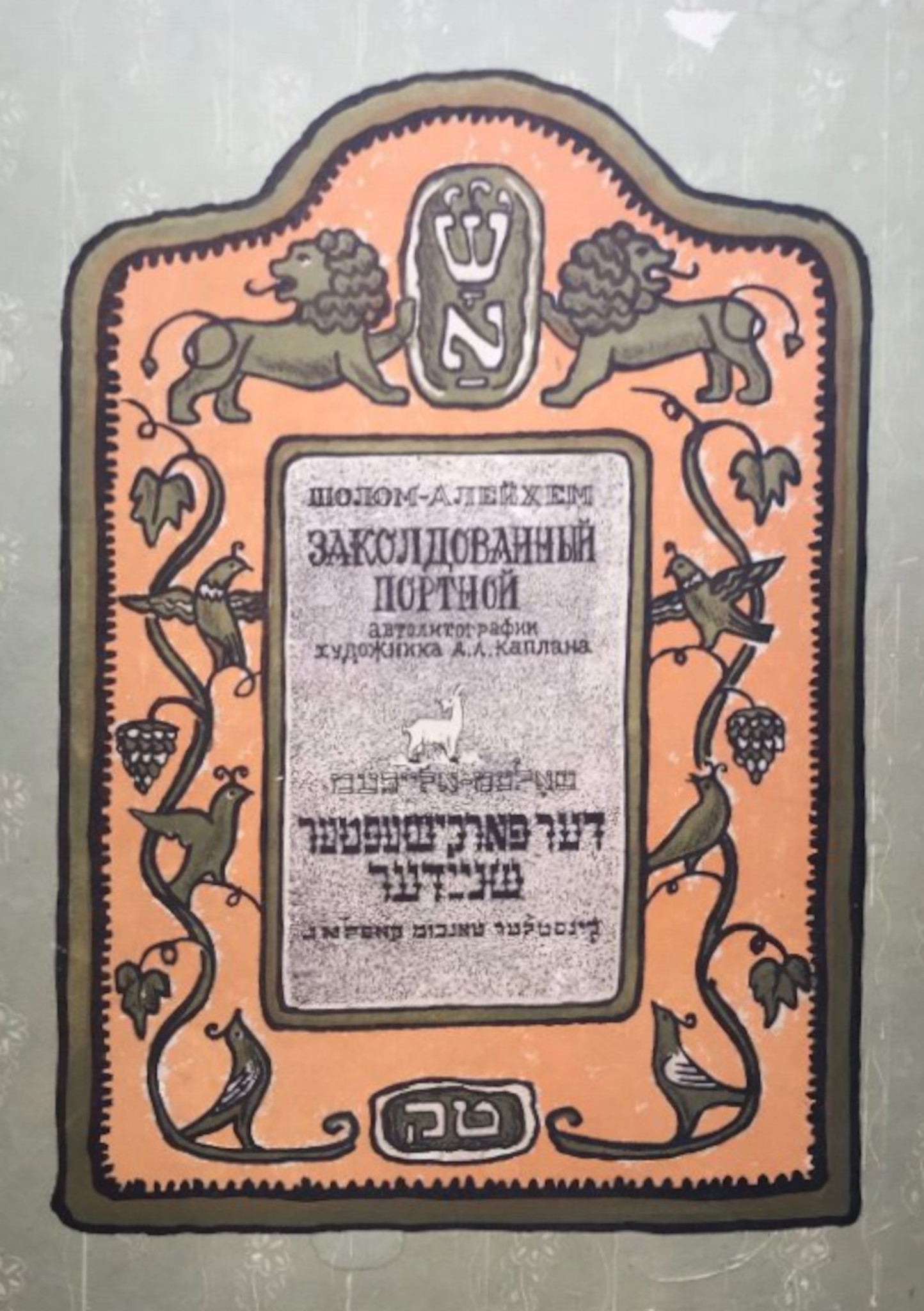

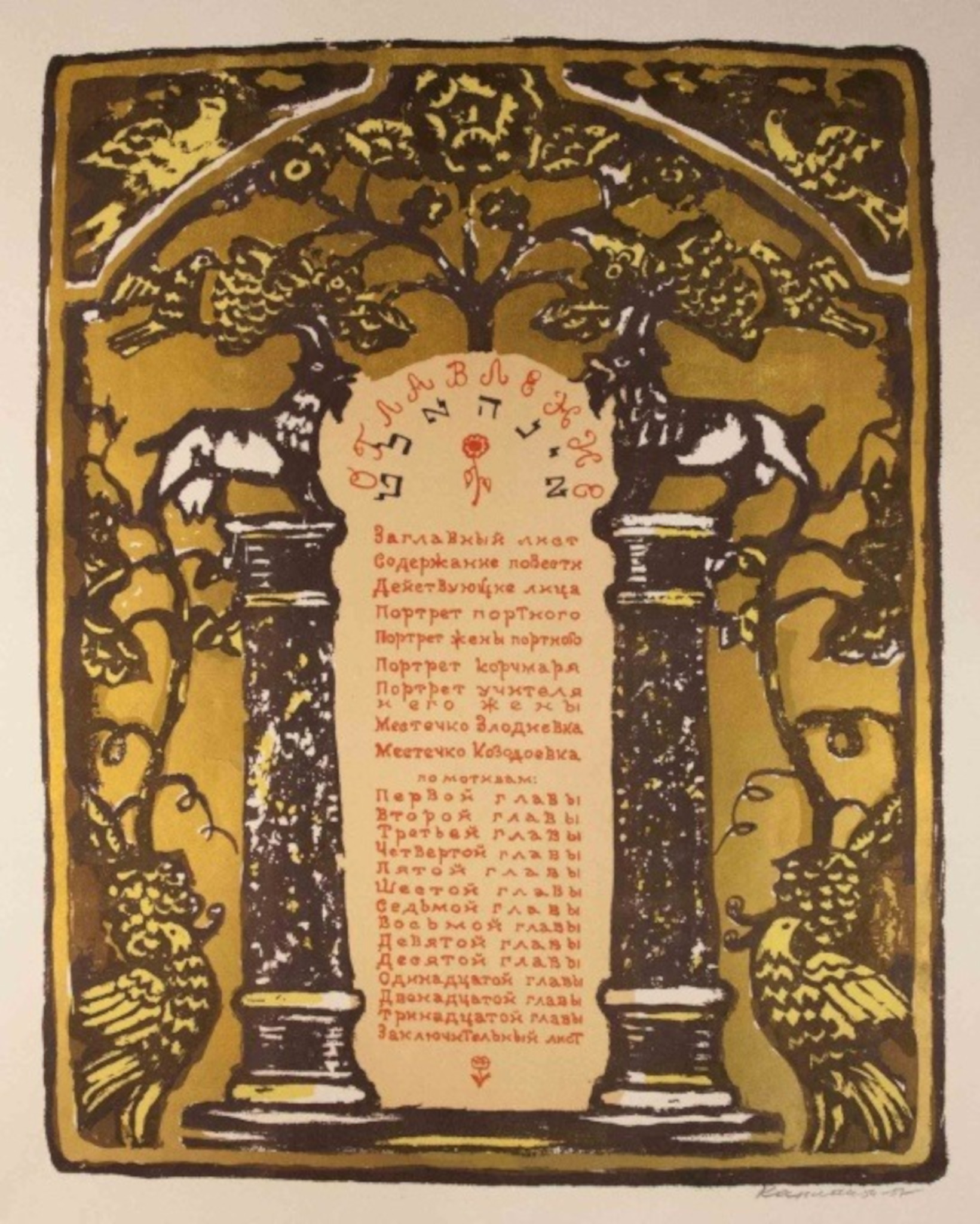

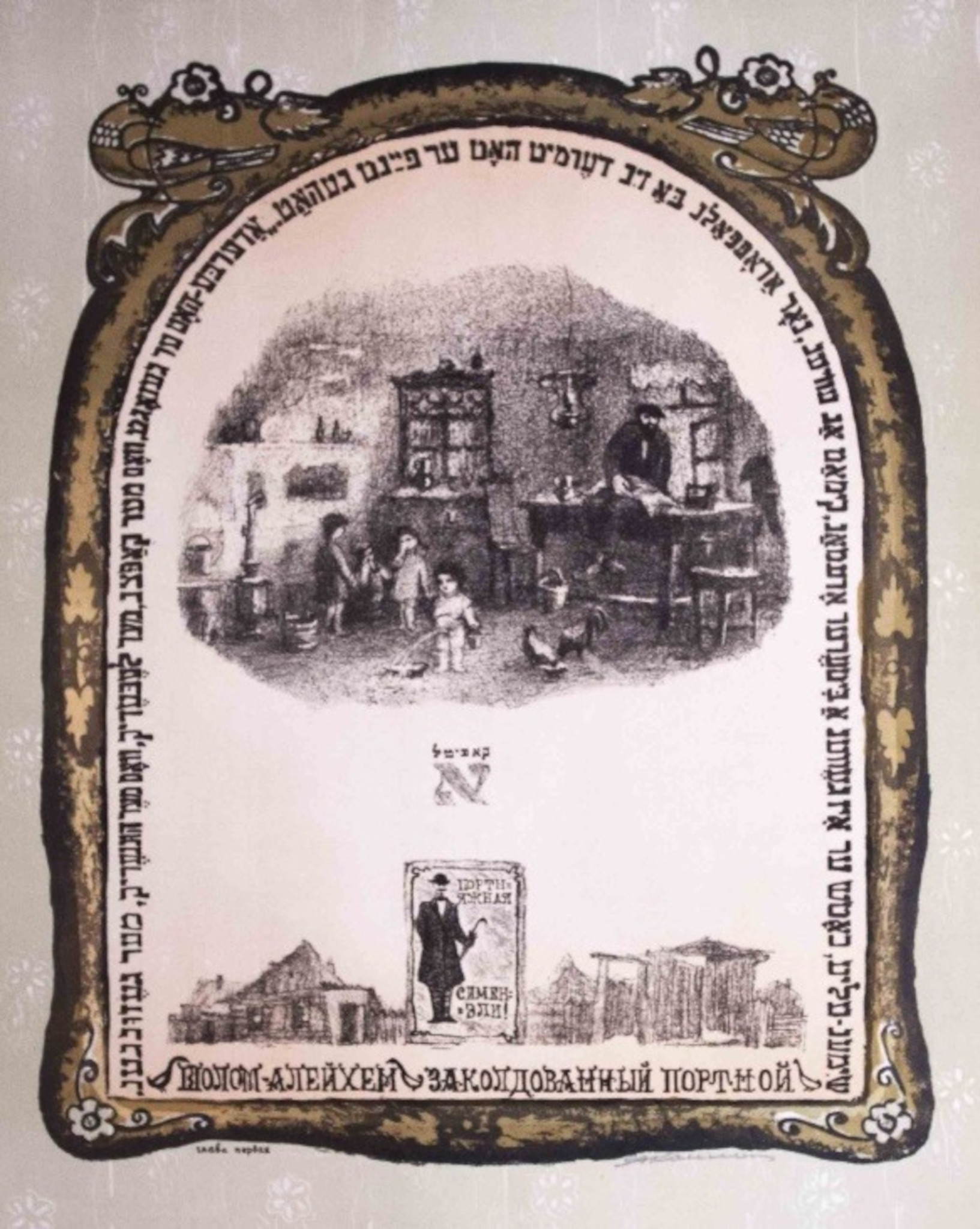

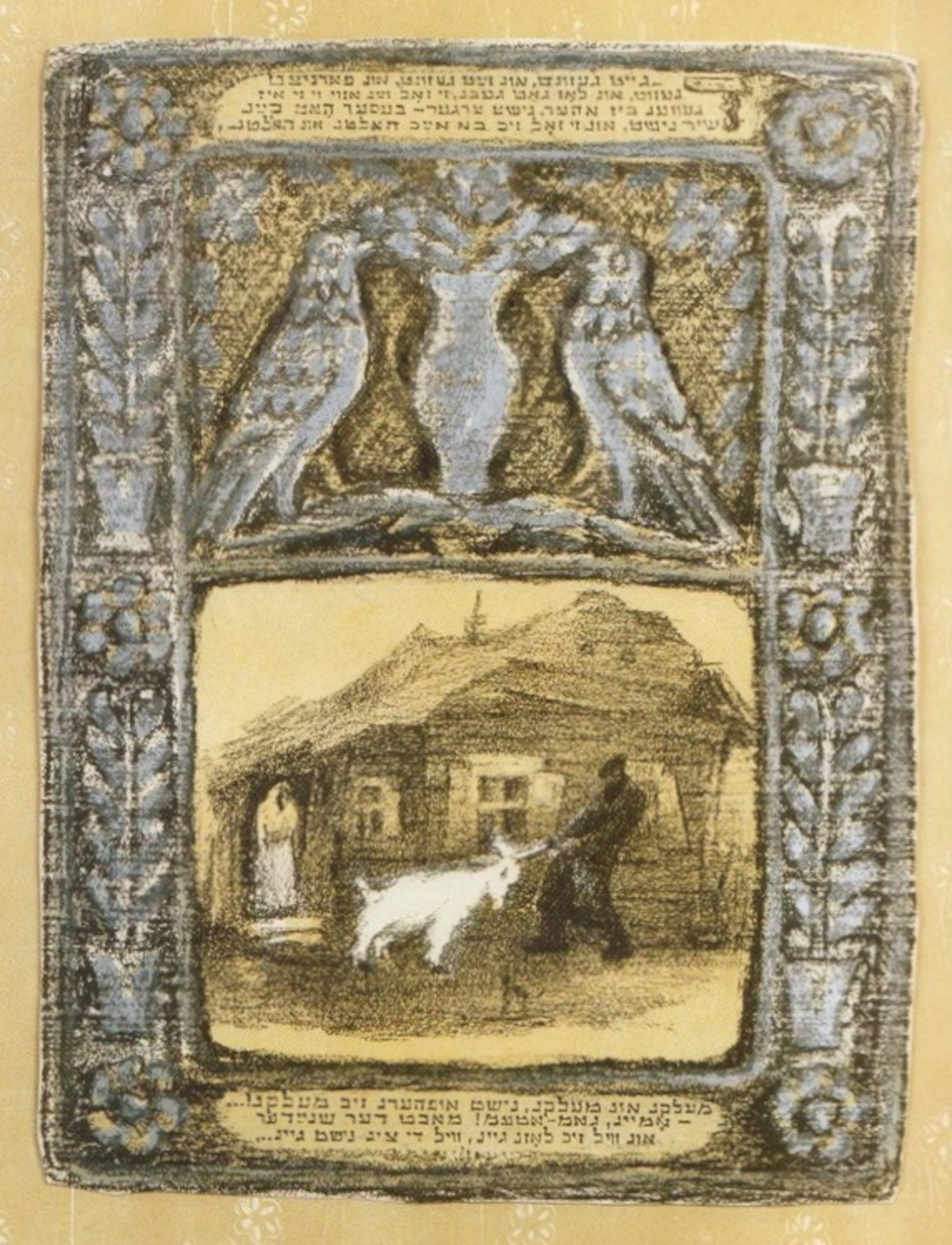

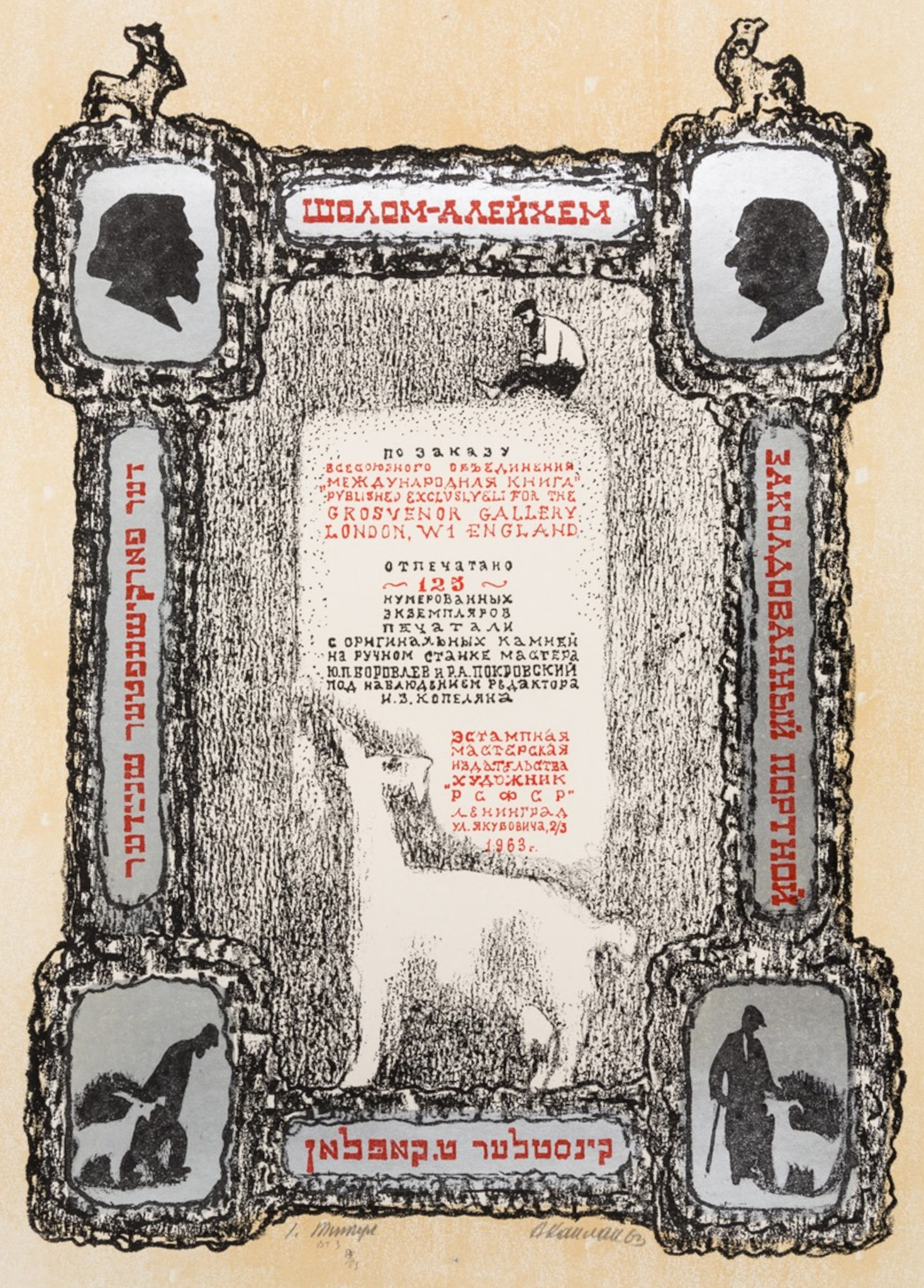

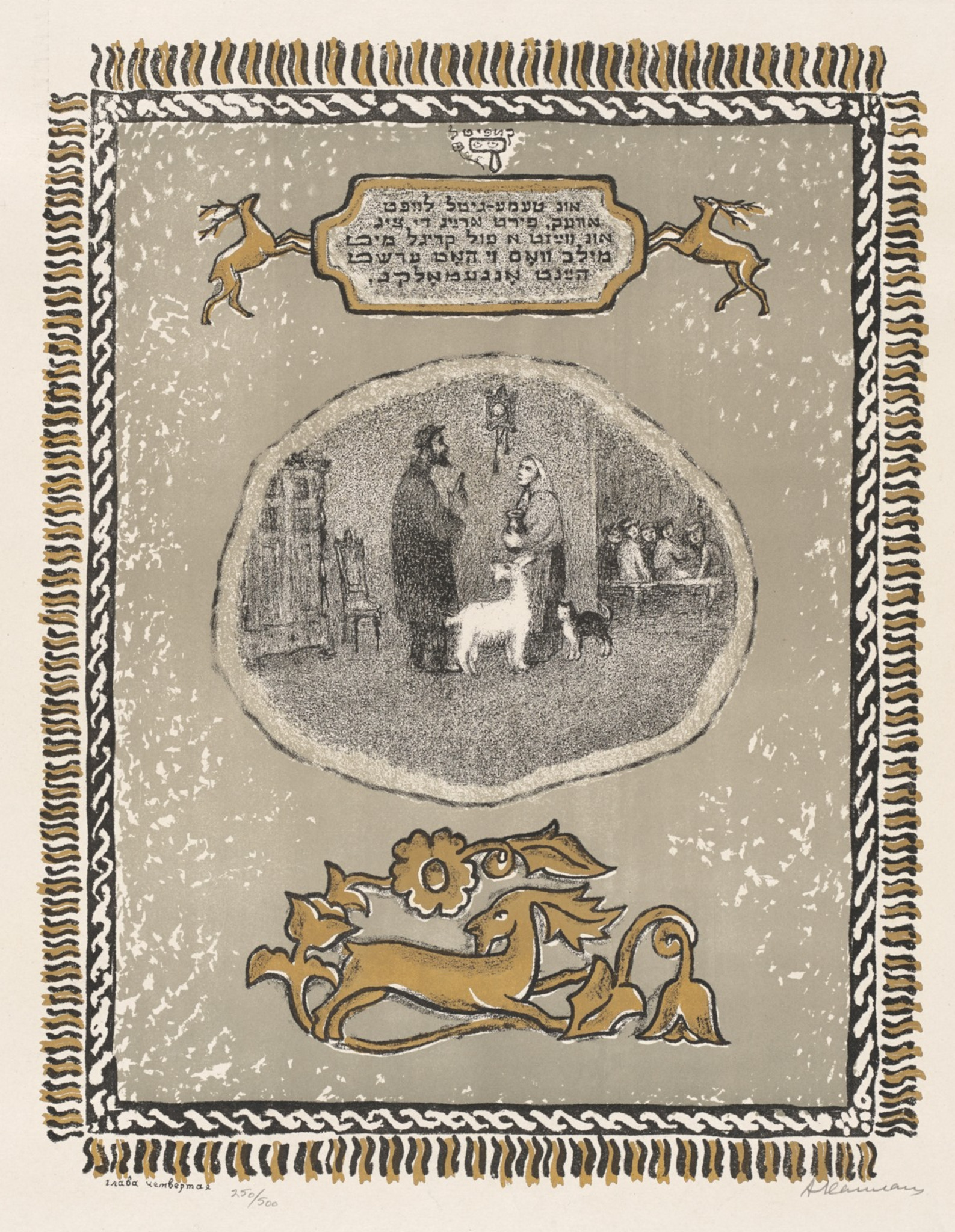

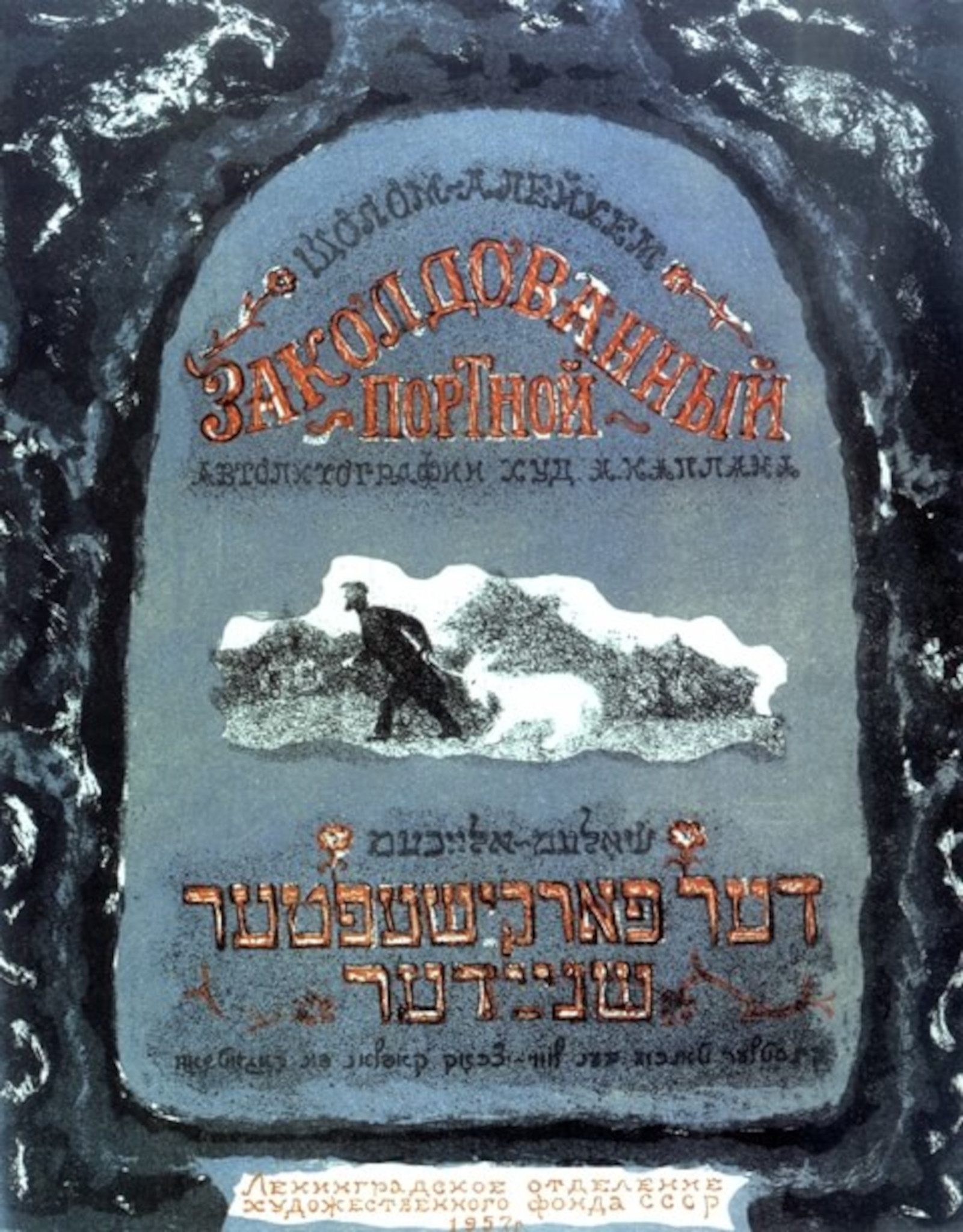

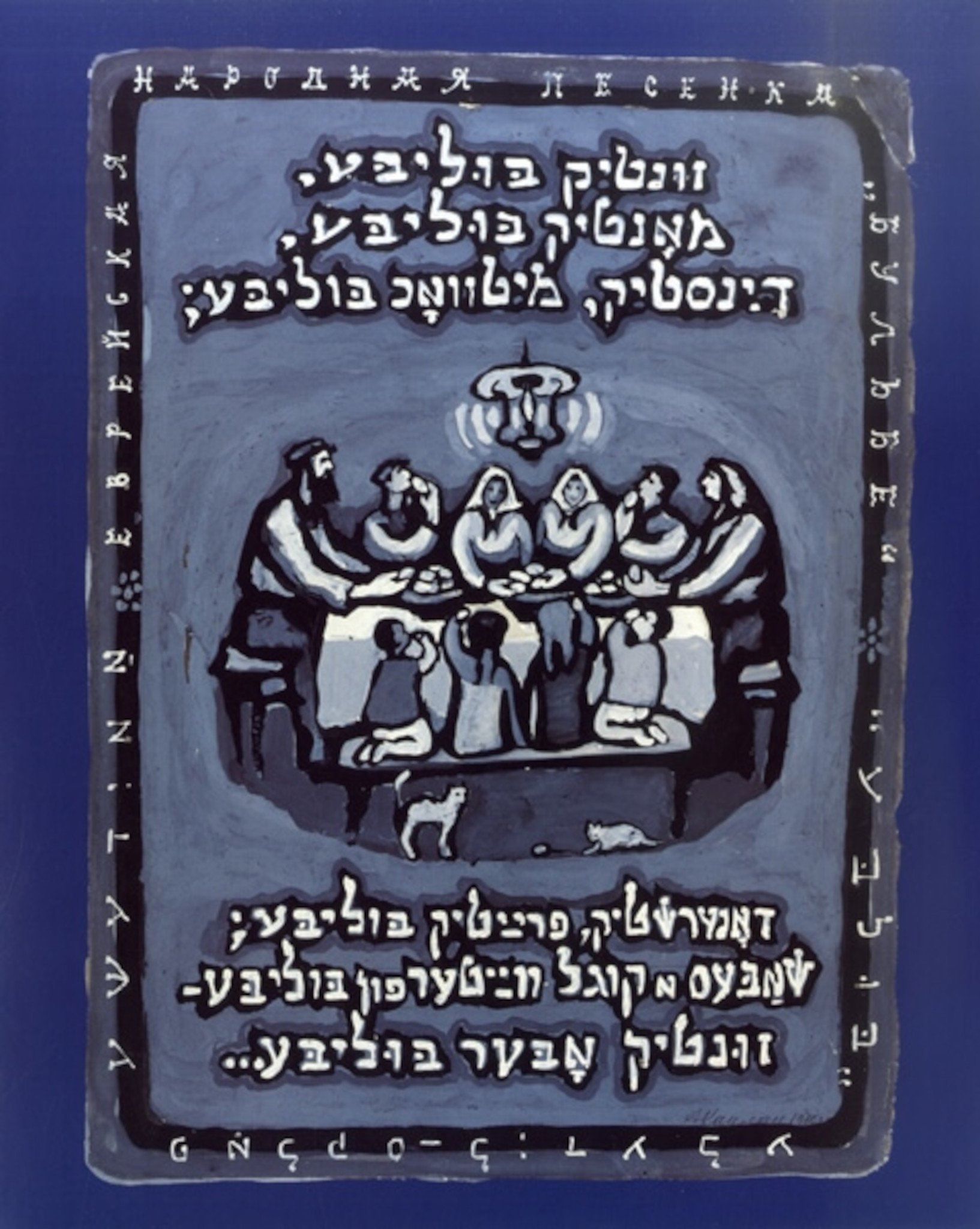

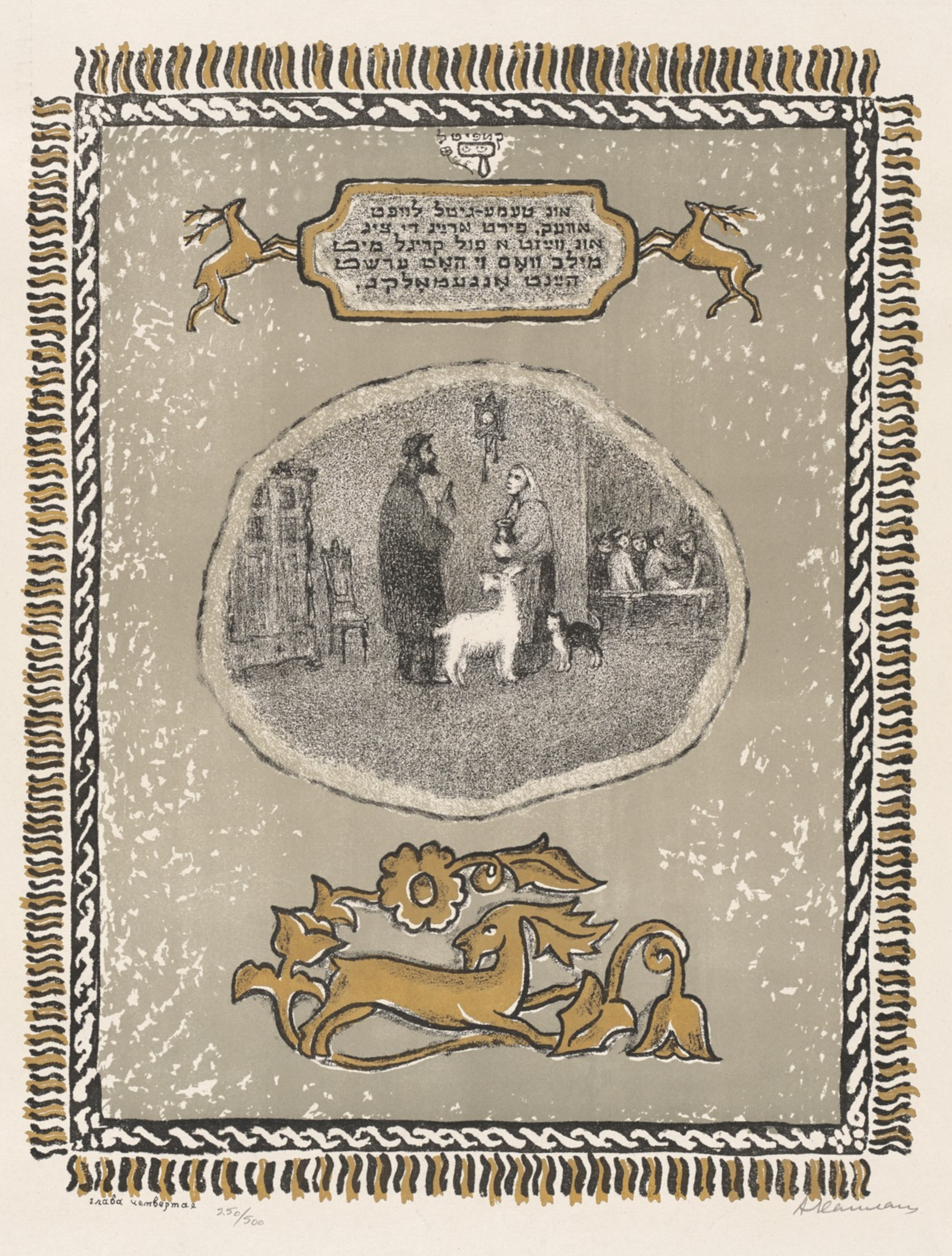

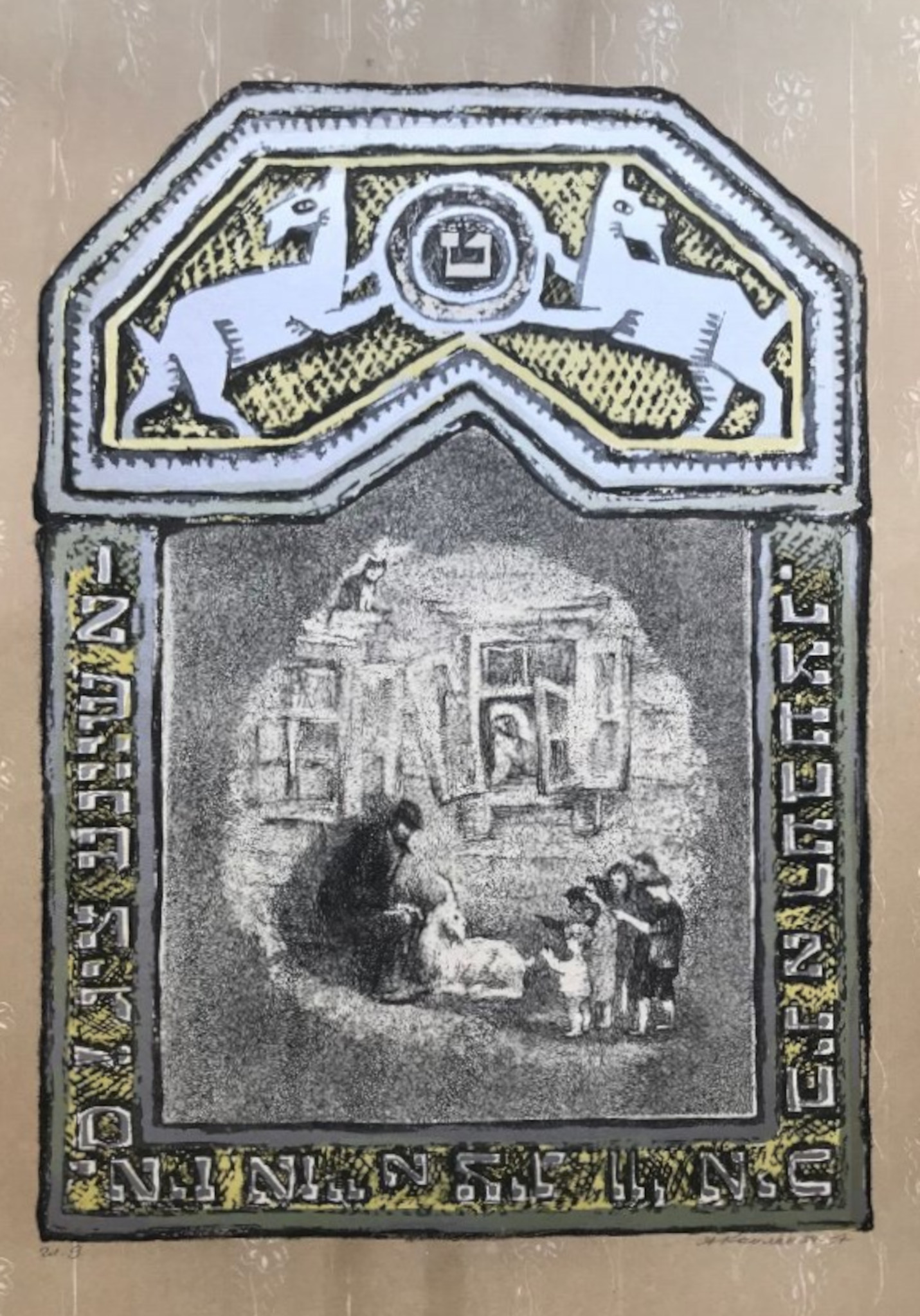

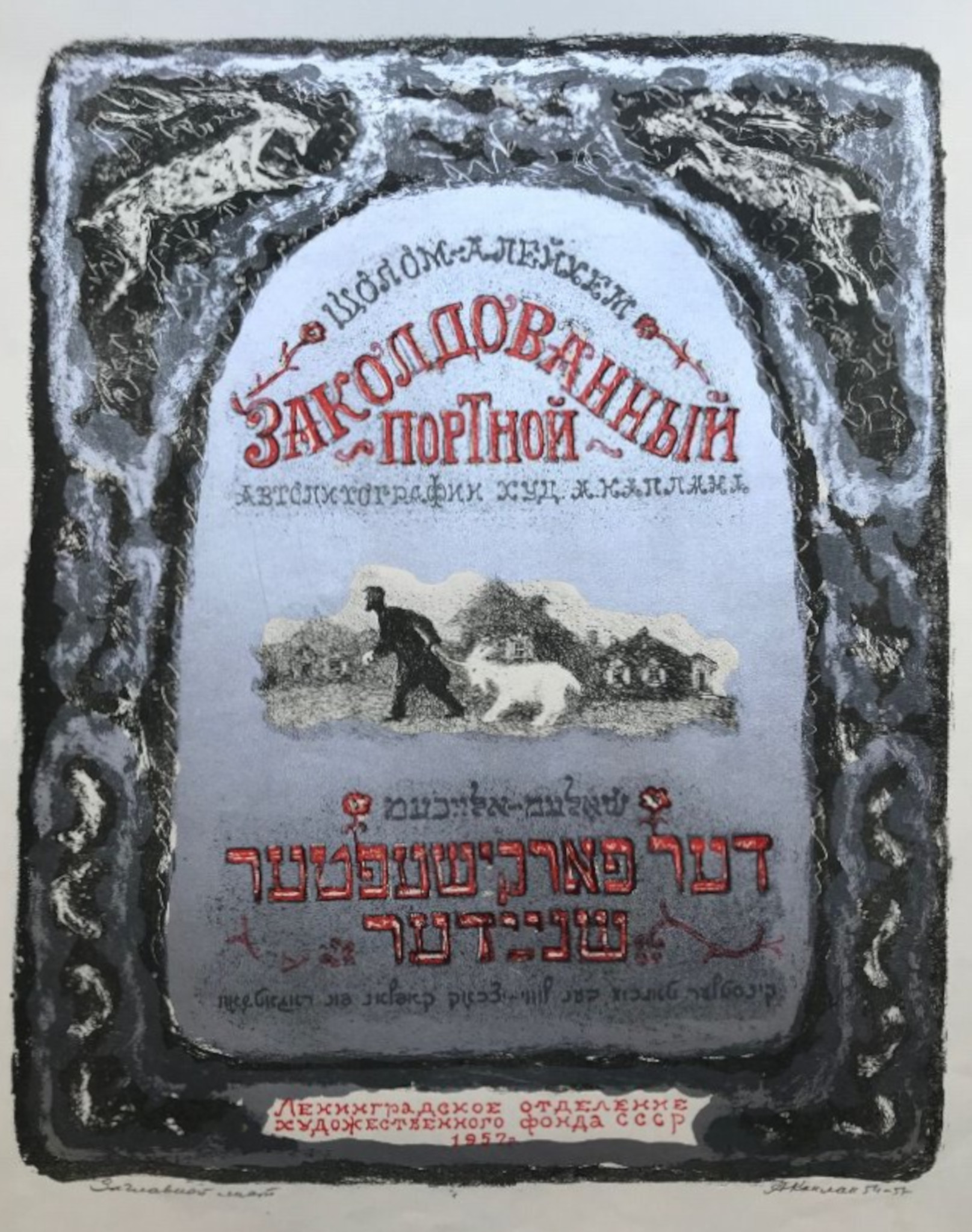

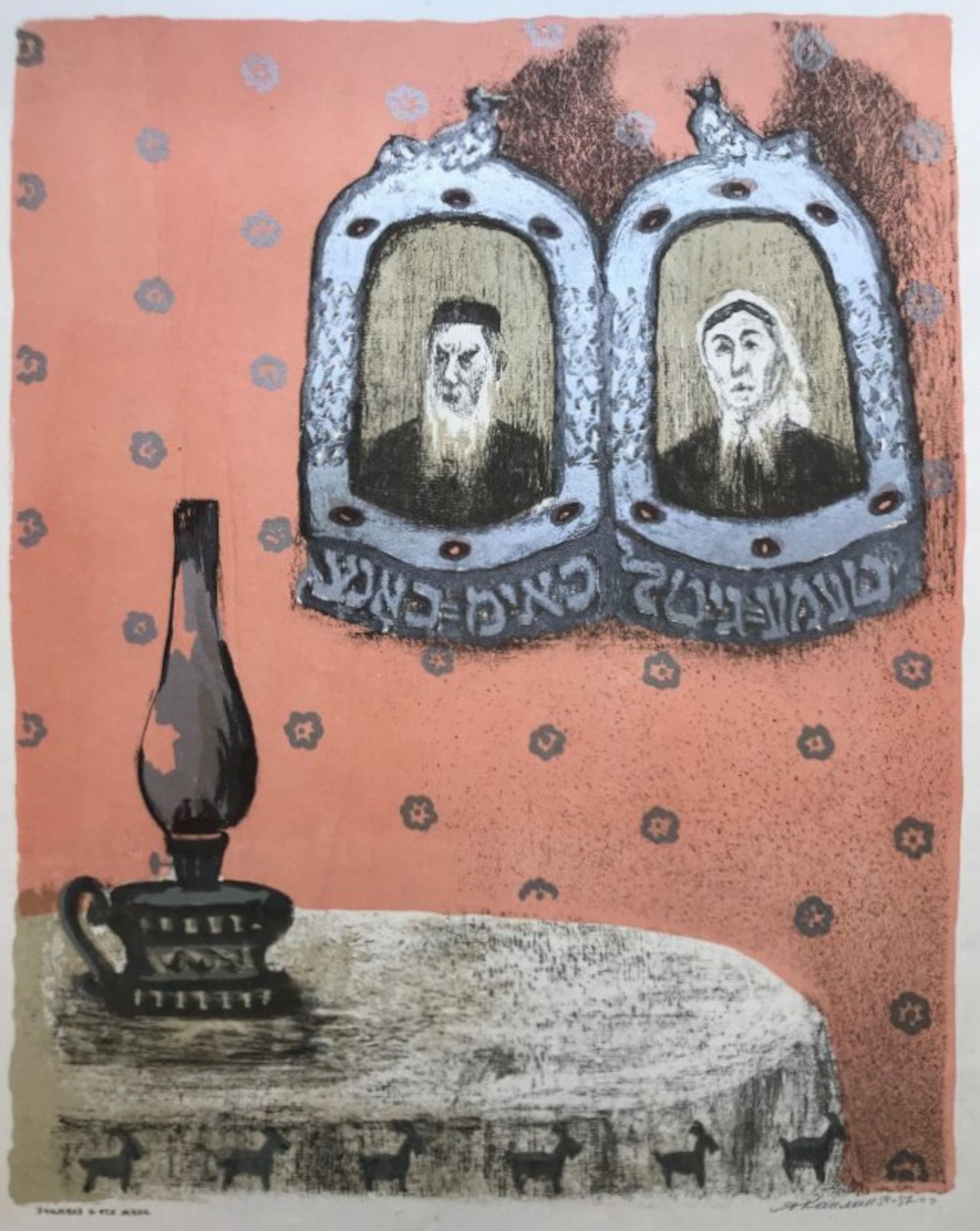

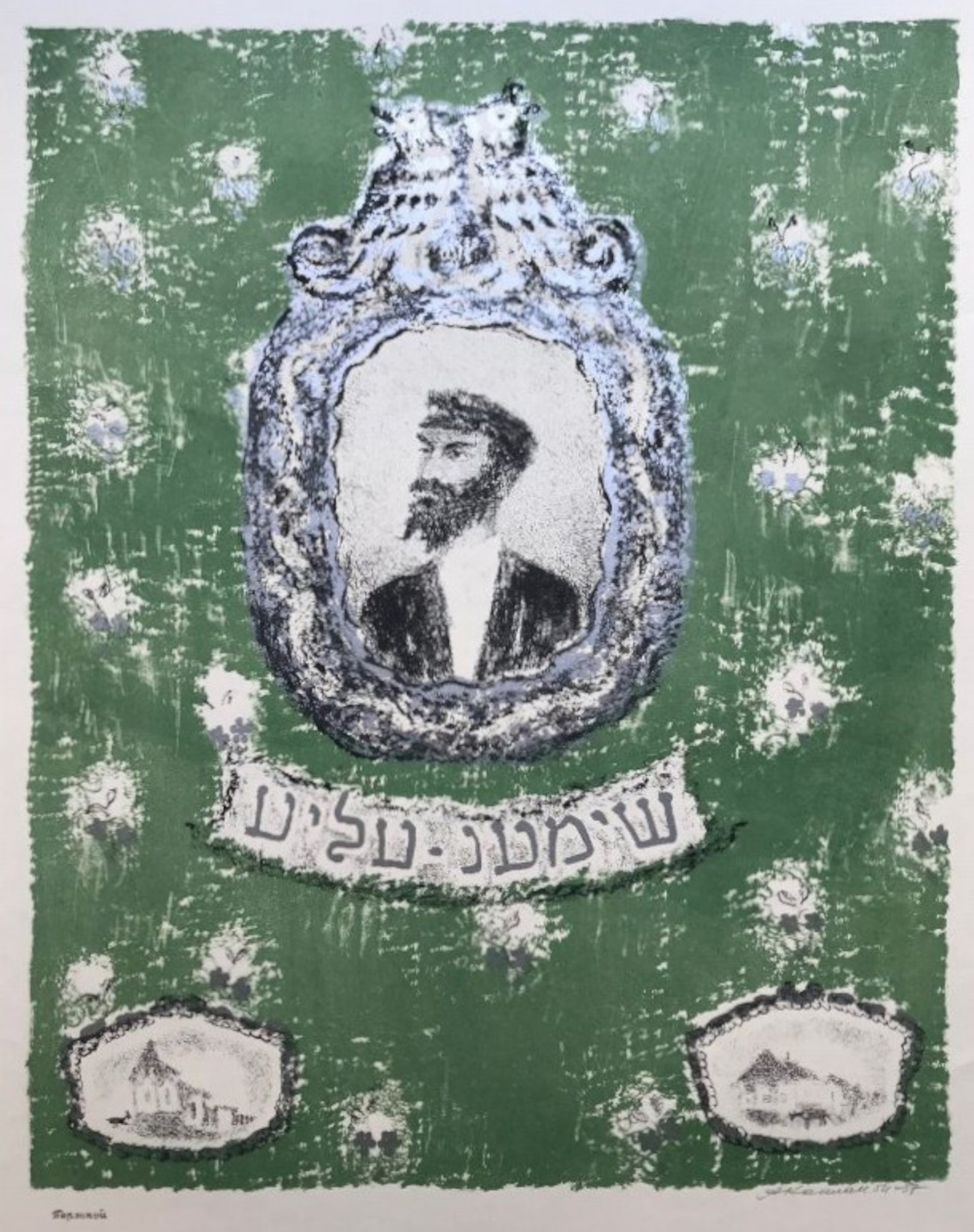

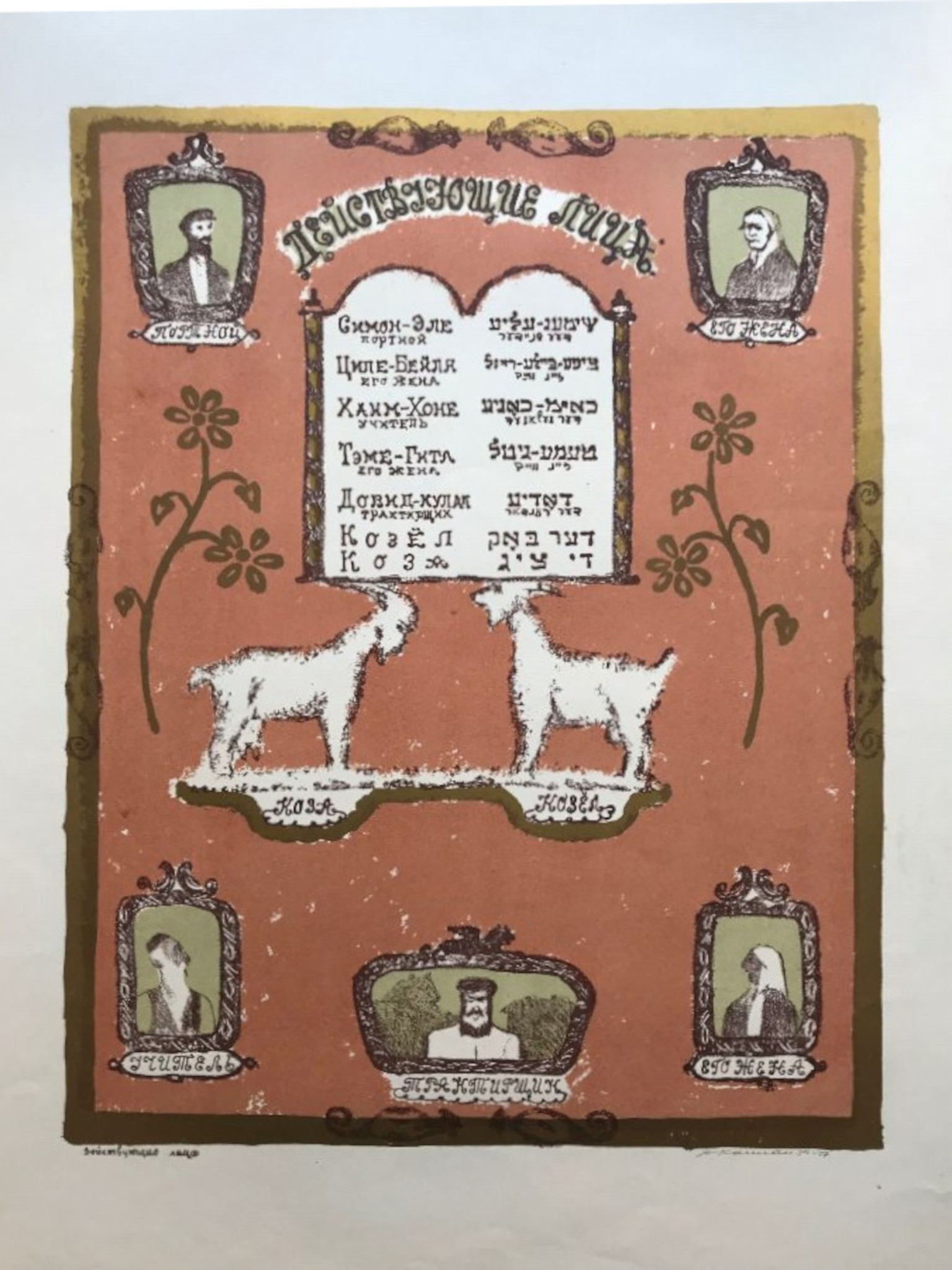

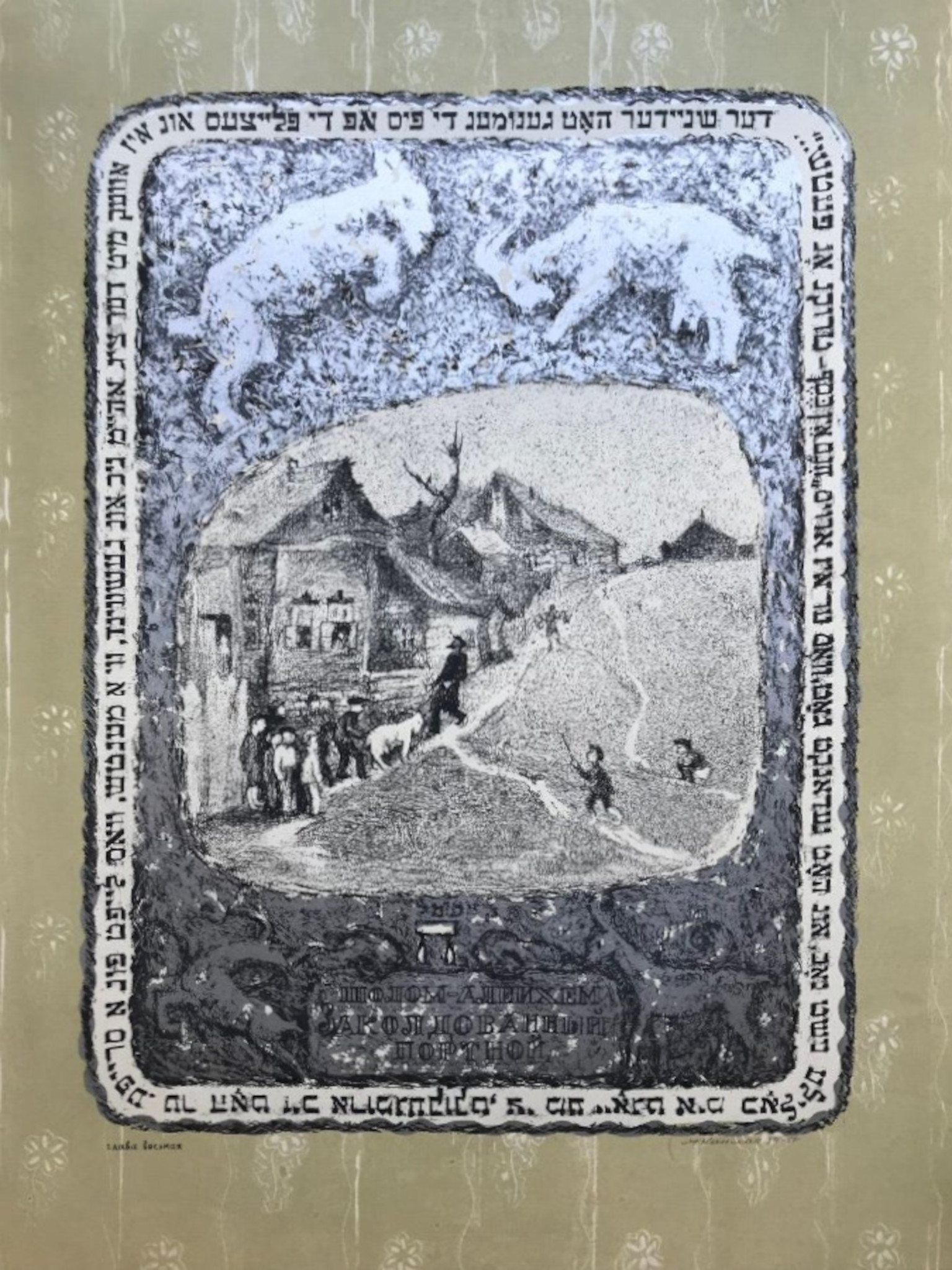

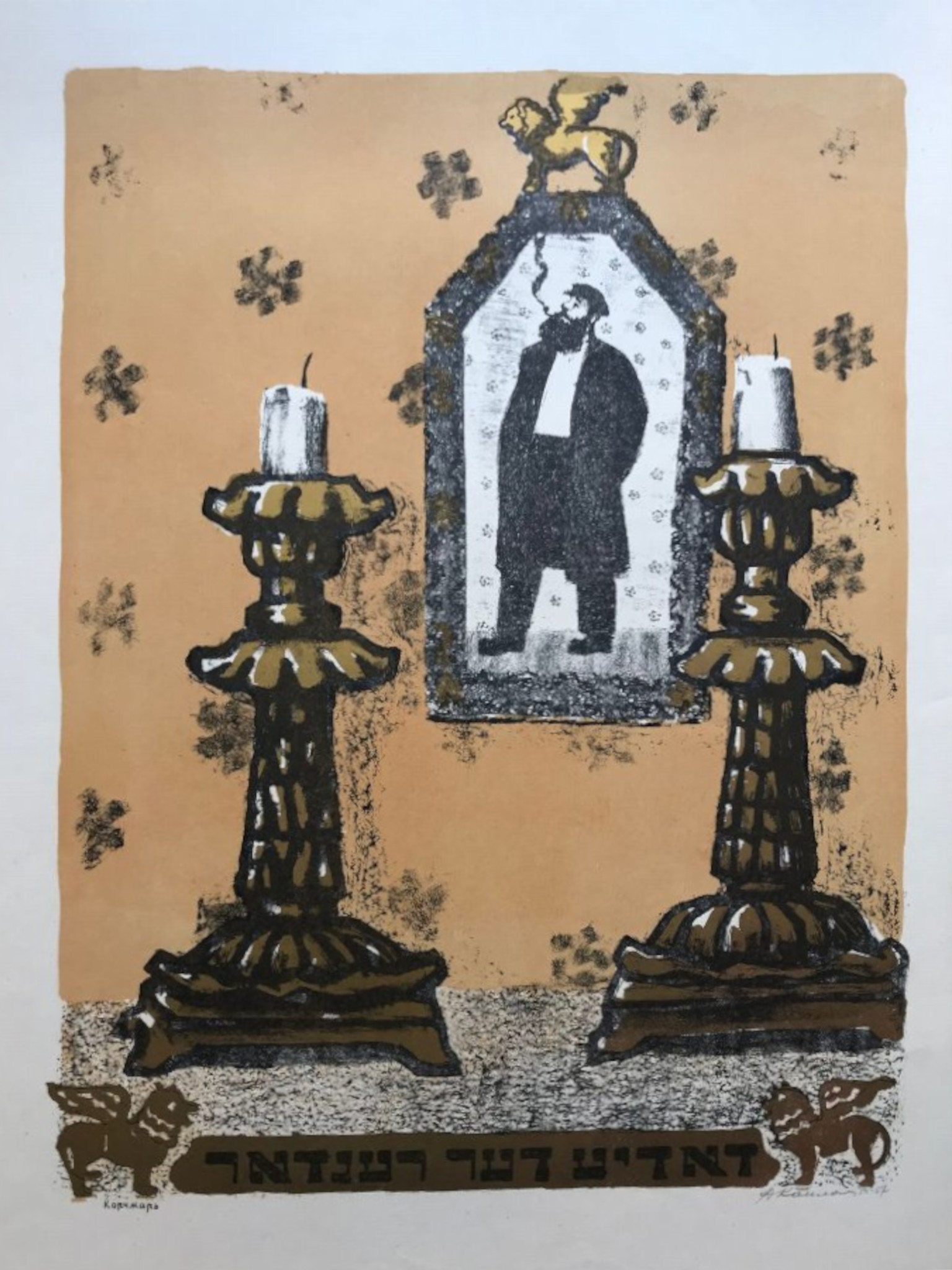

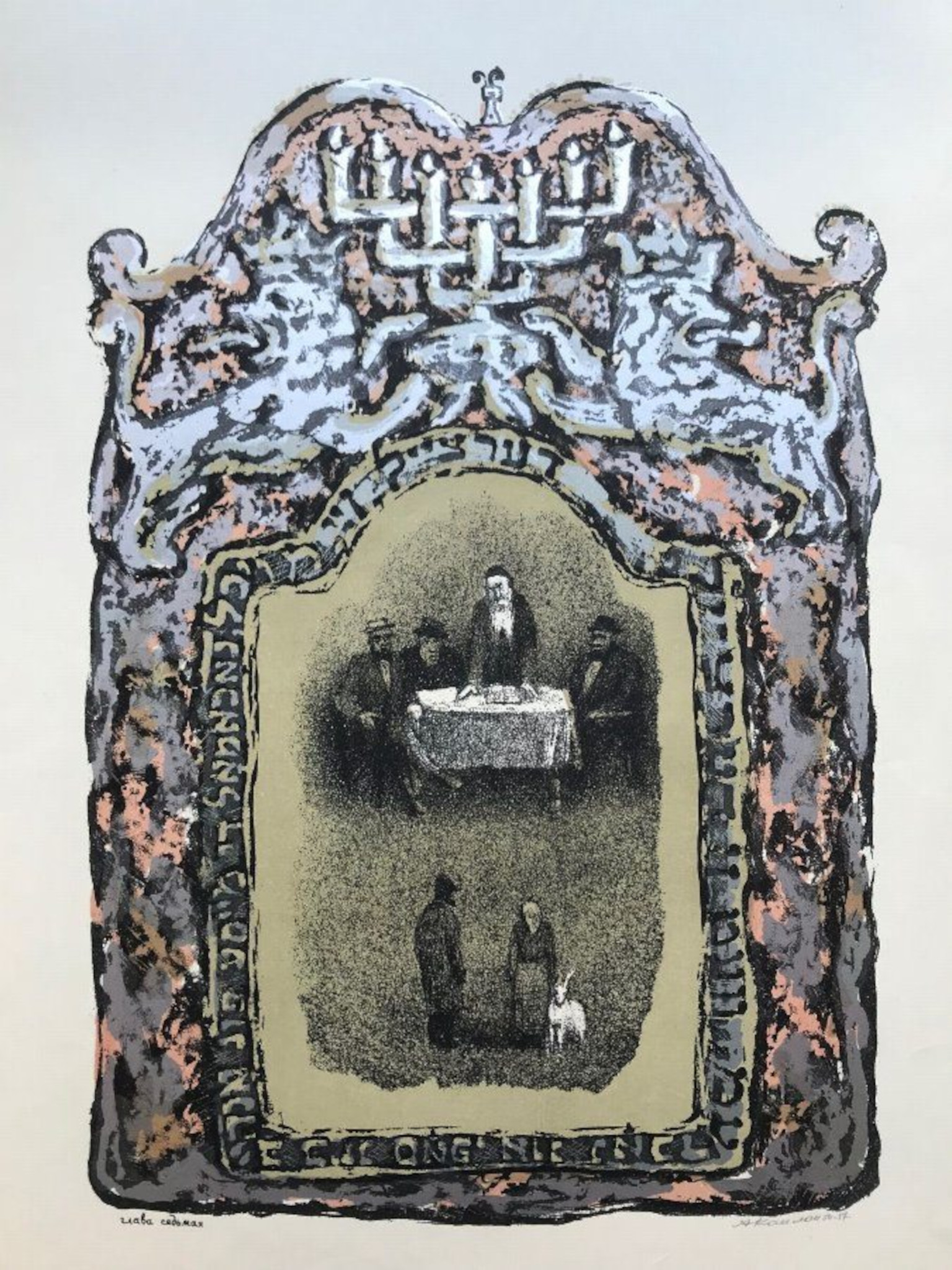

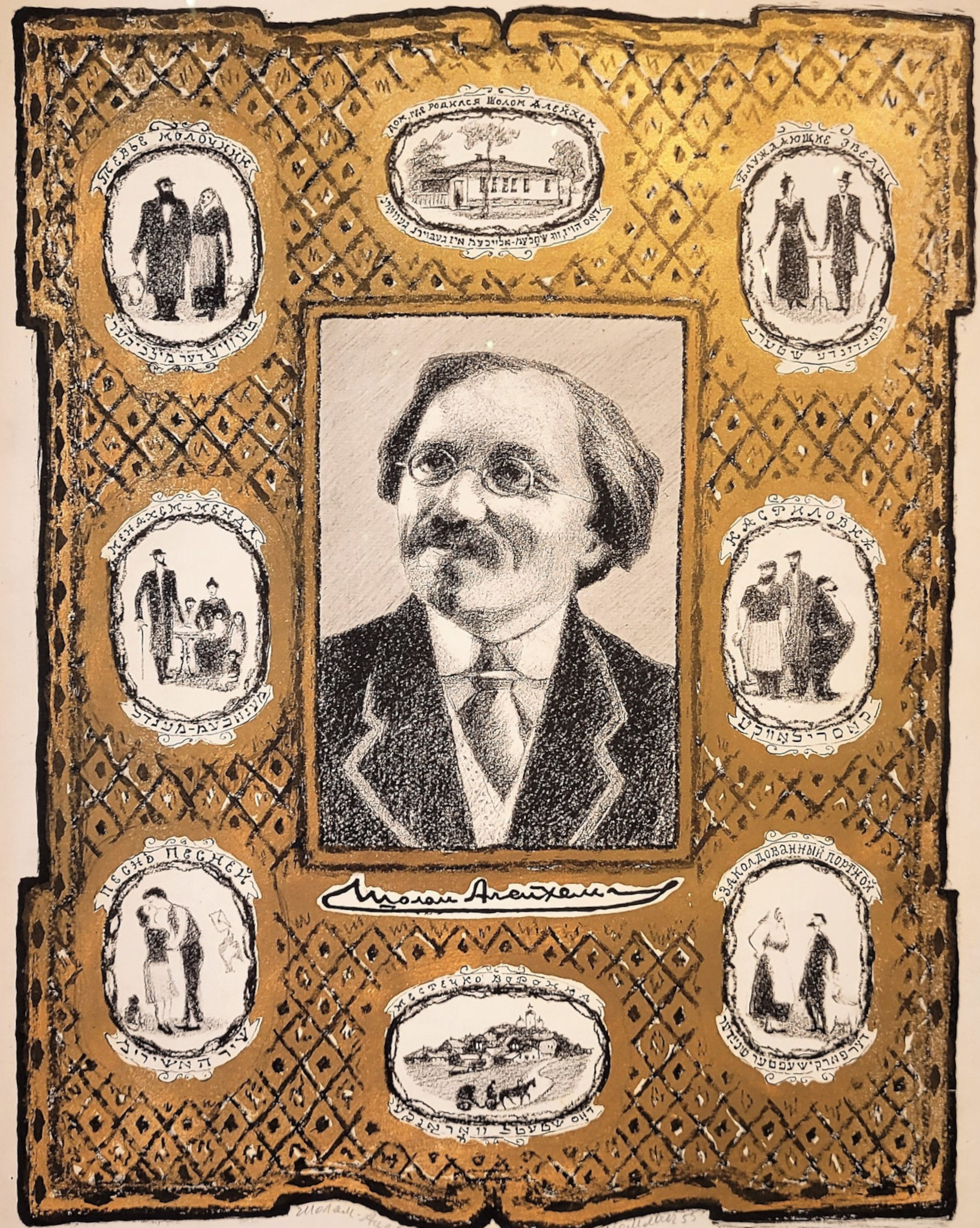

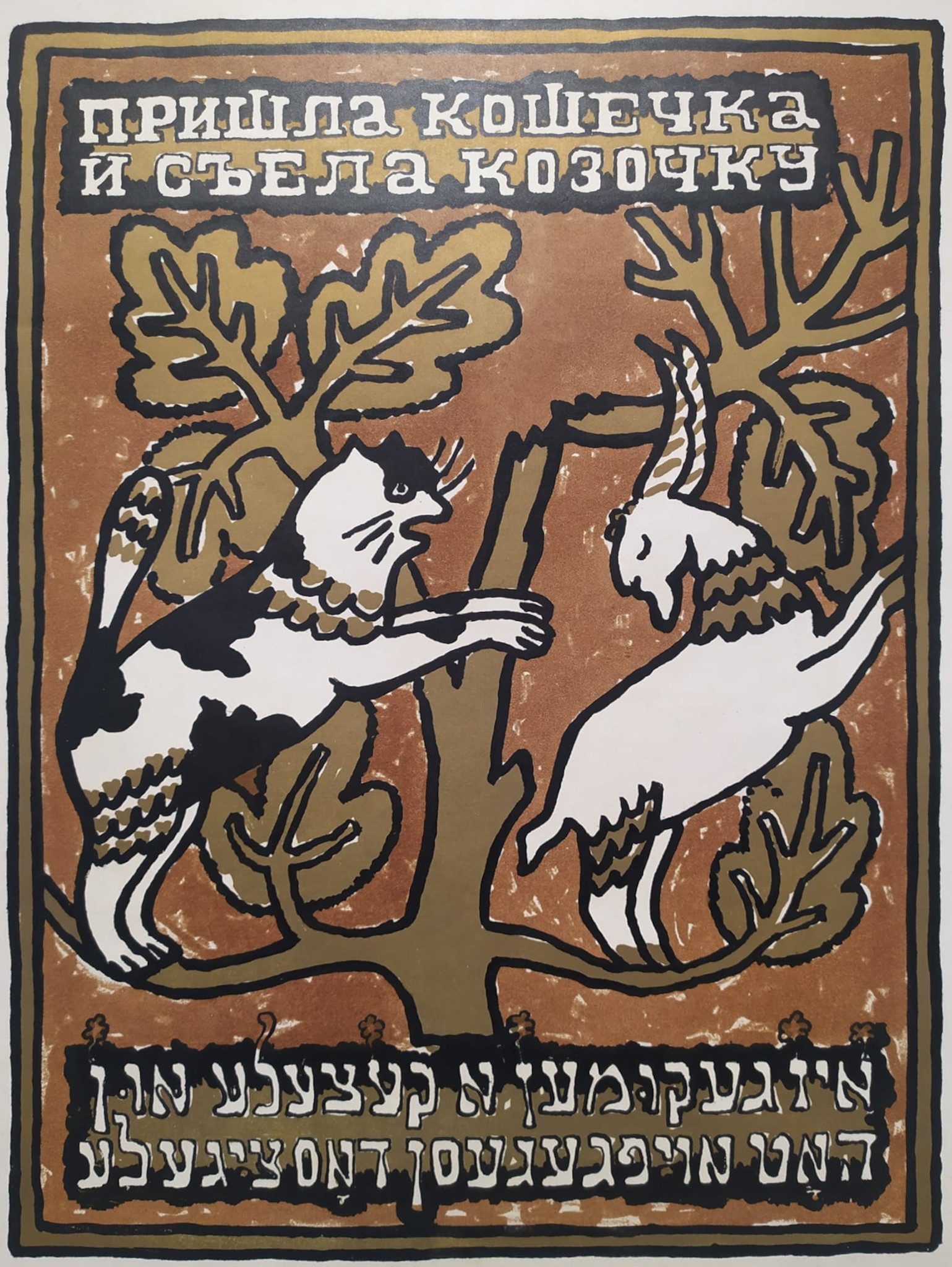

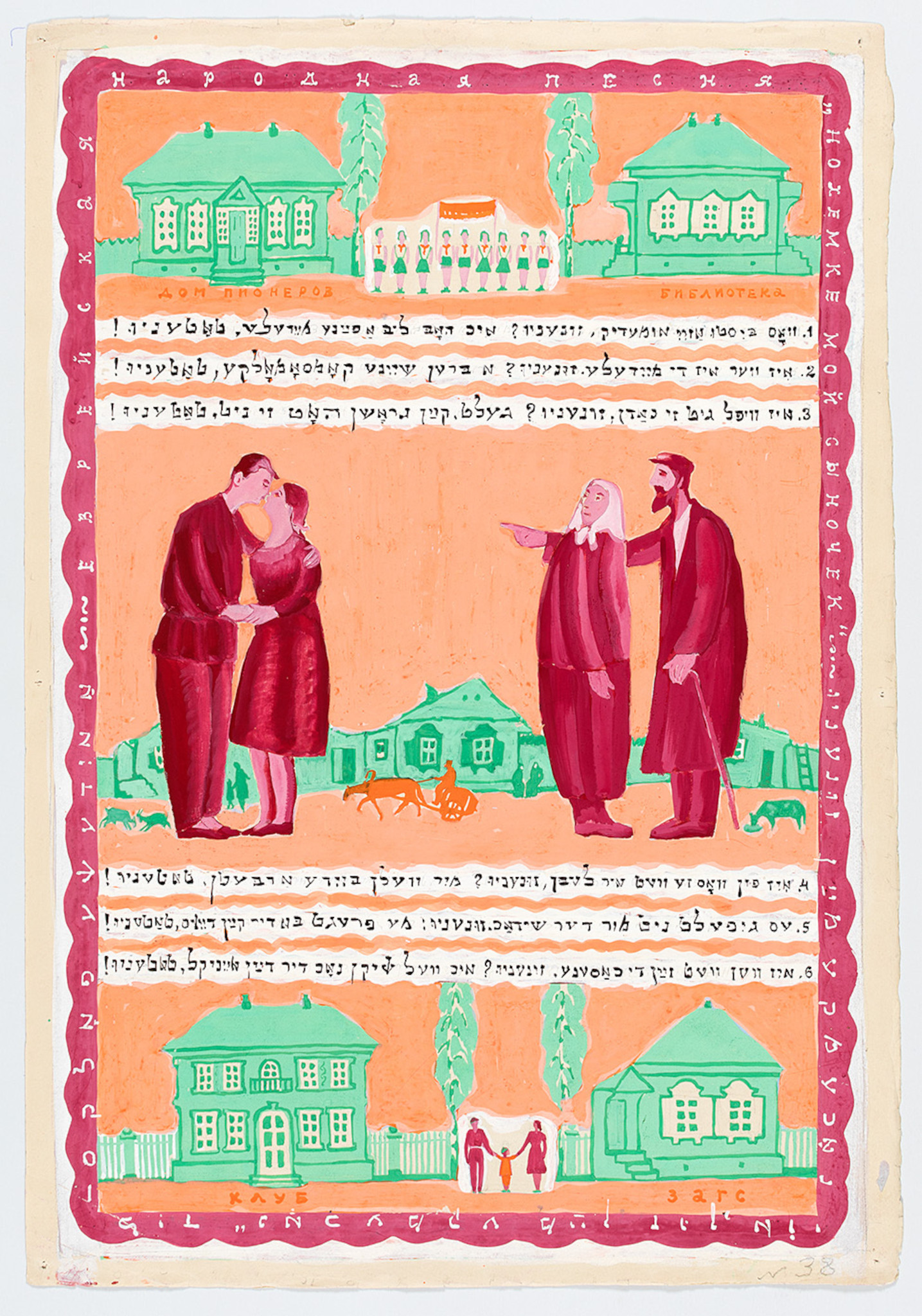

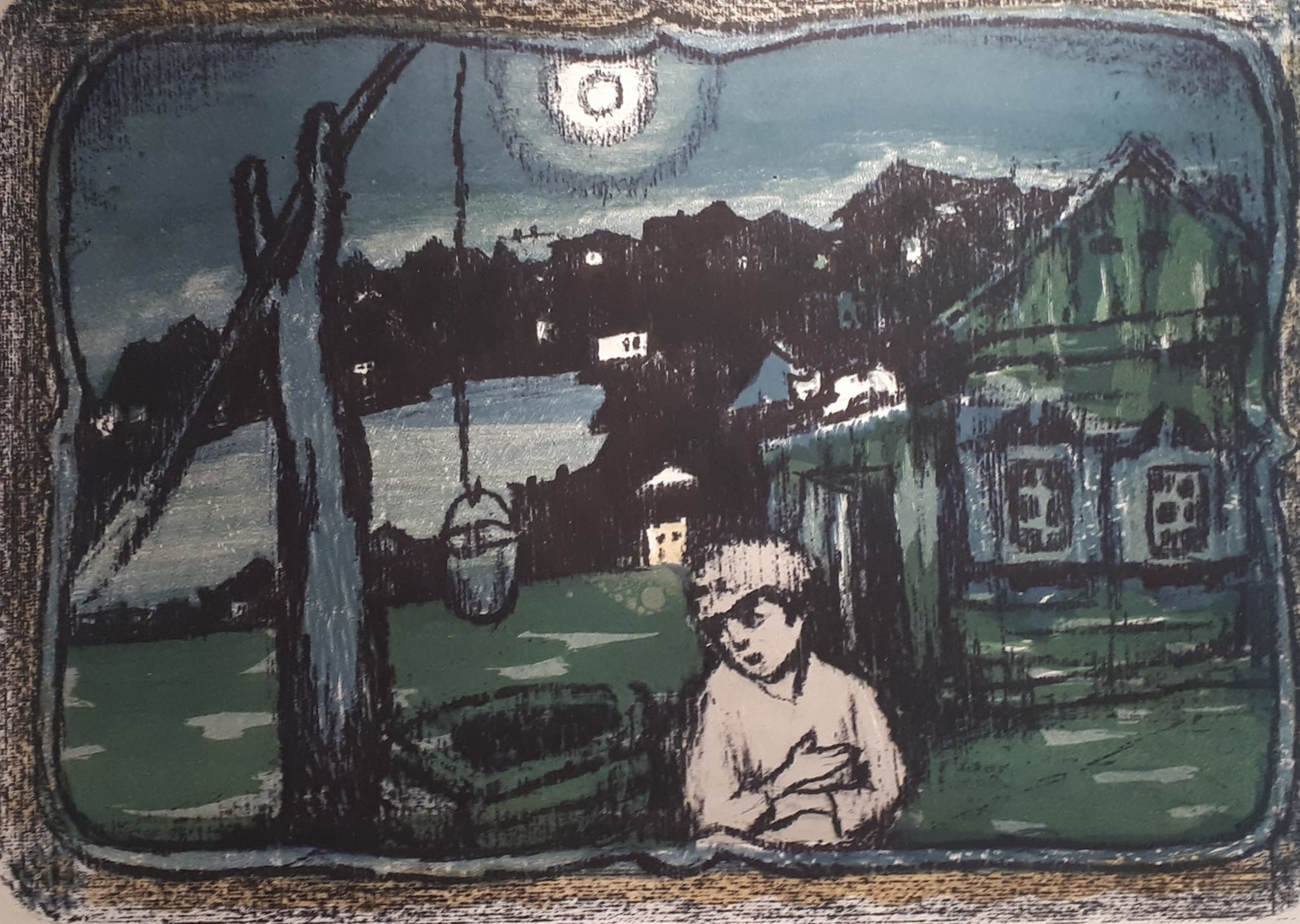

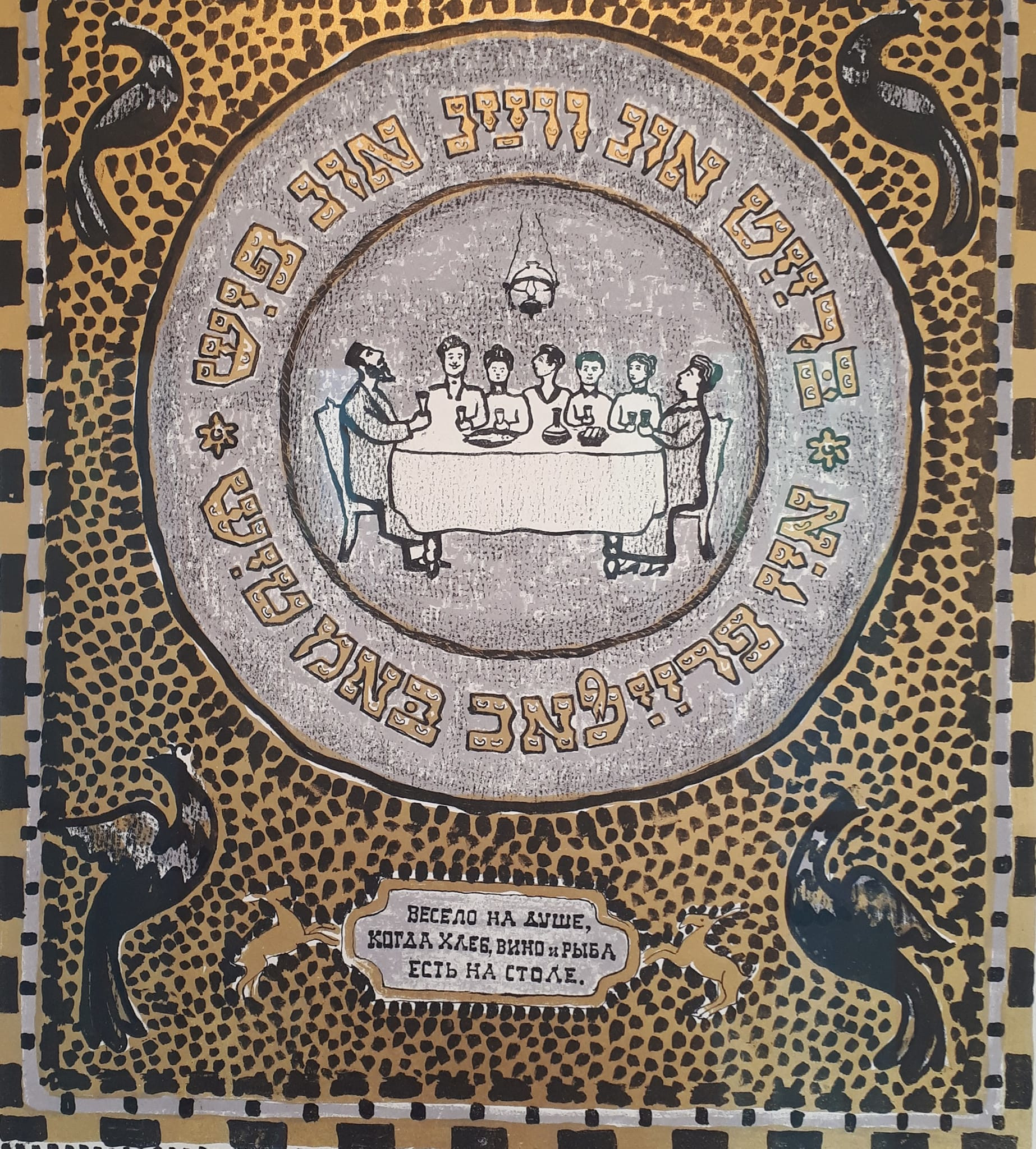

Anatoli Kaplan

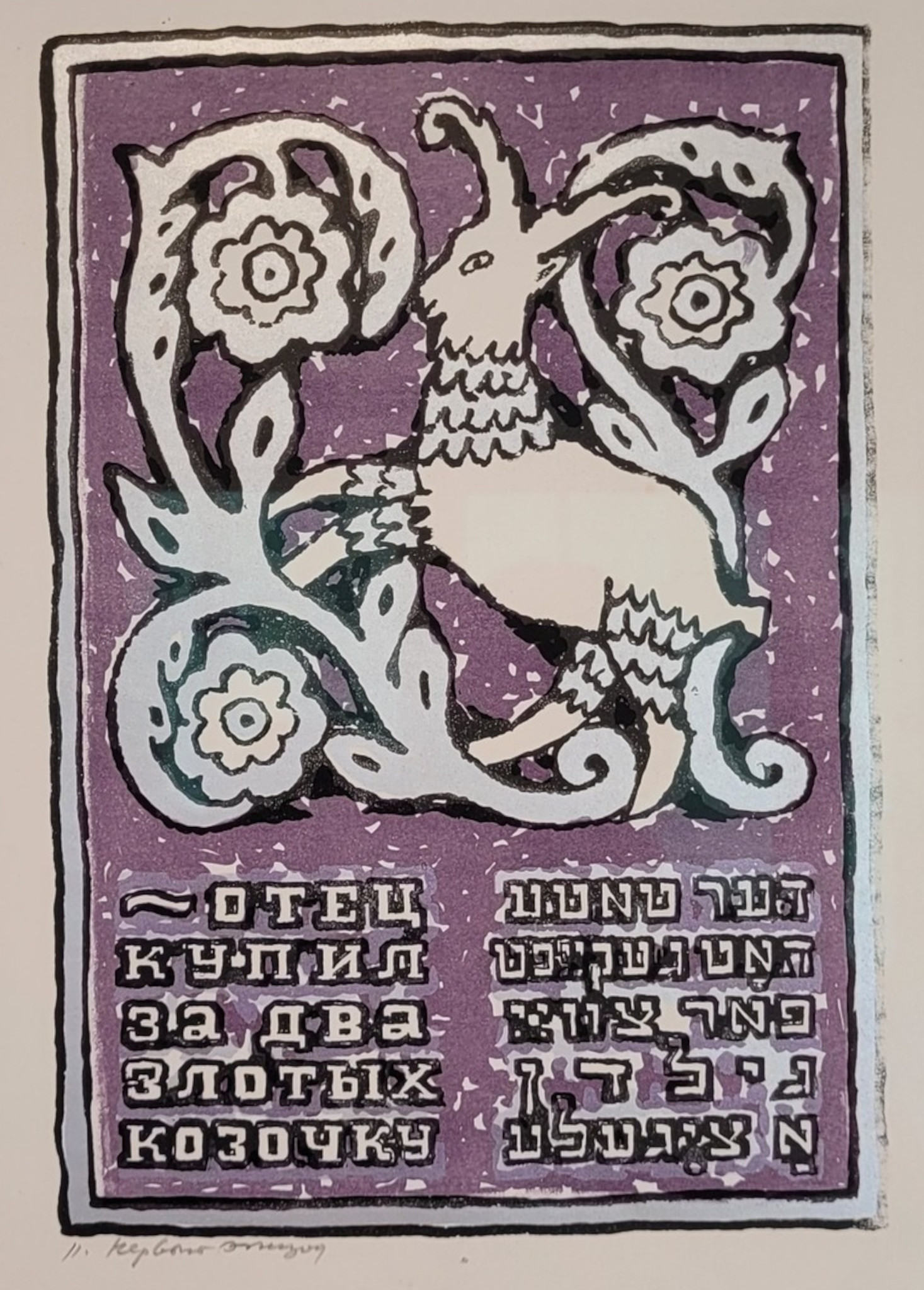

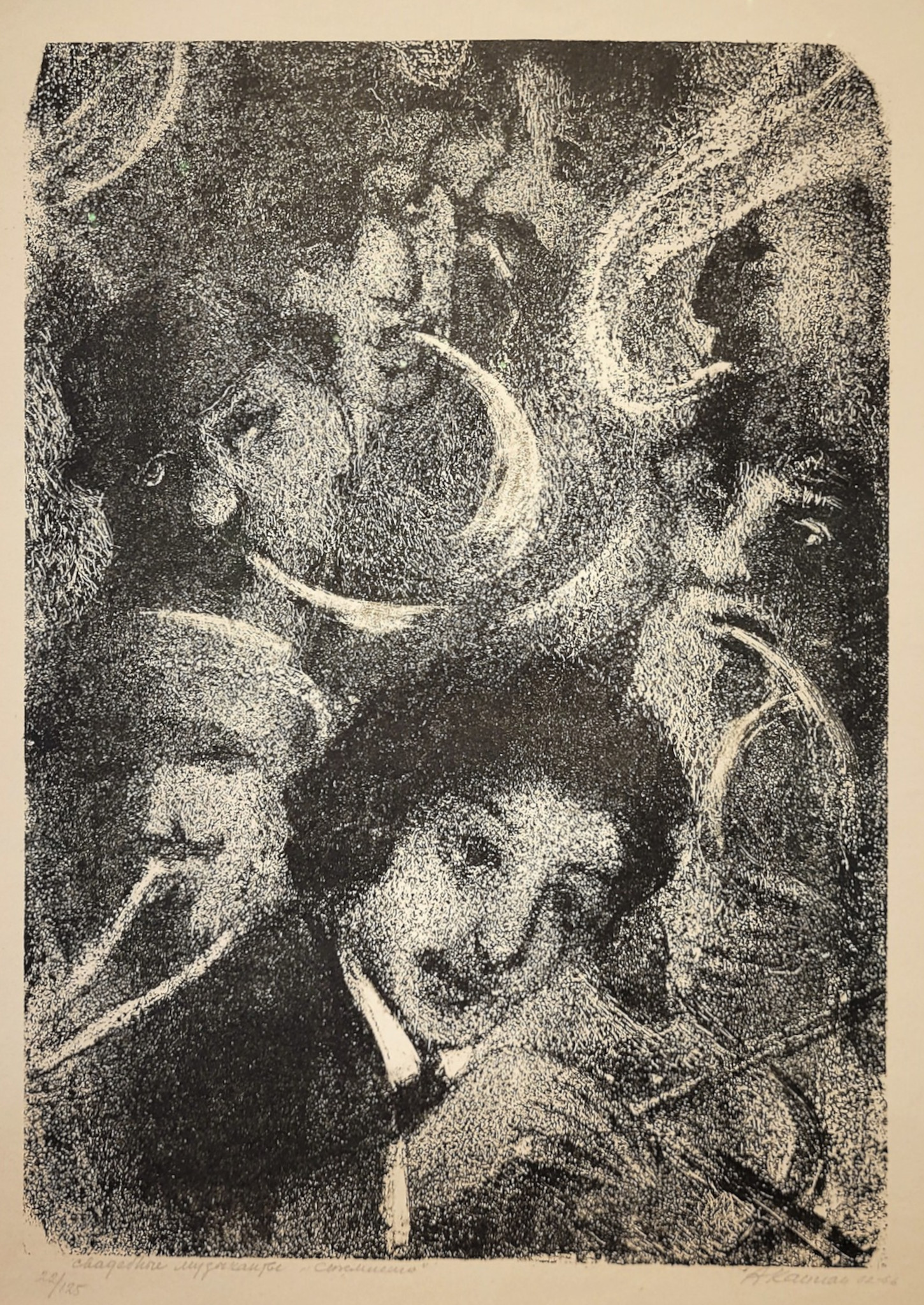

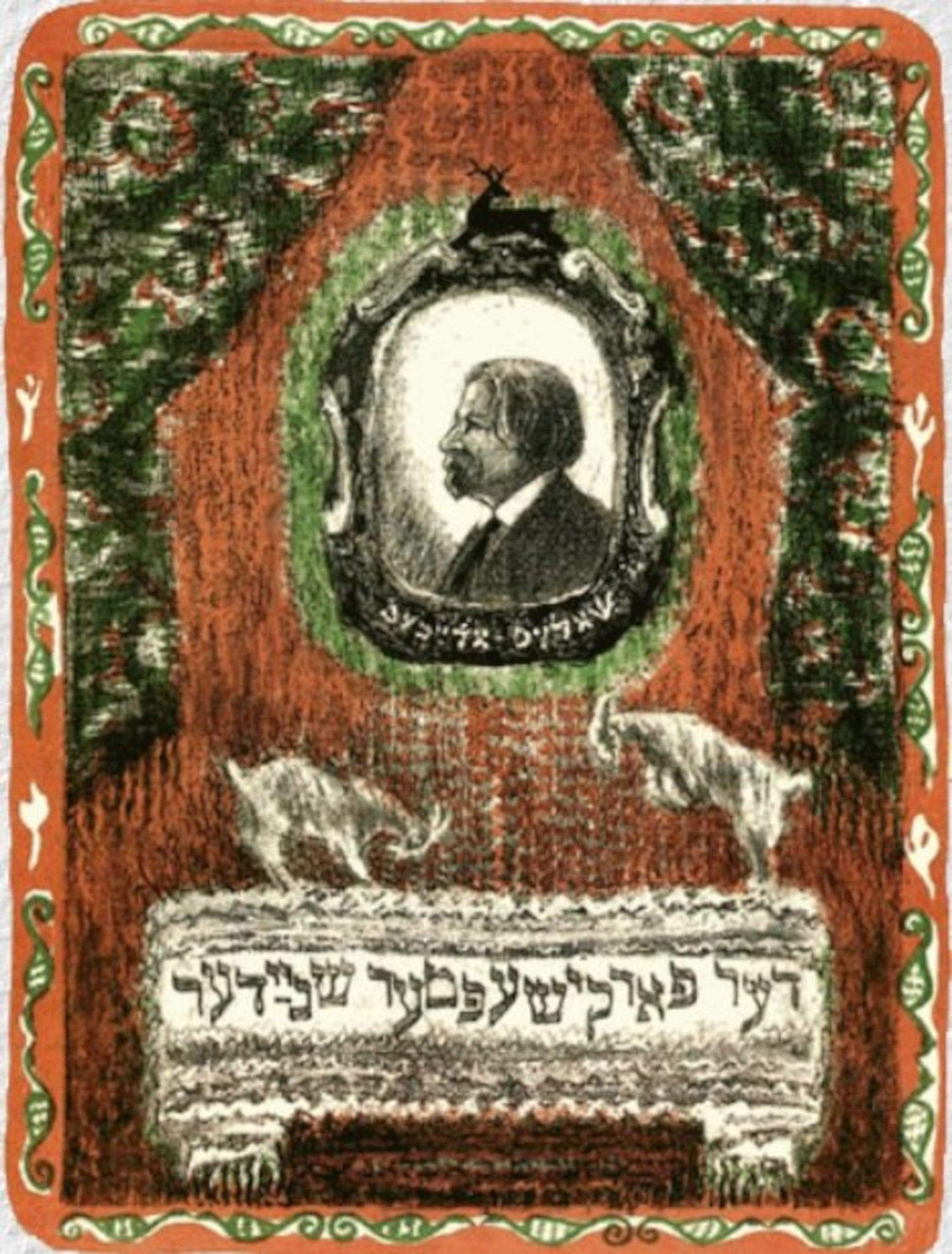

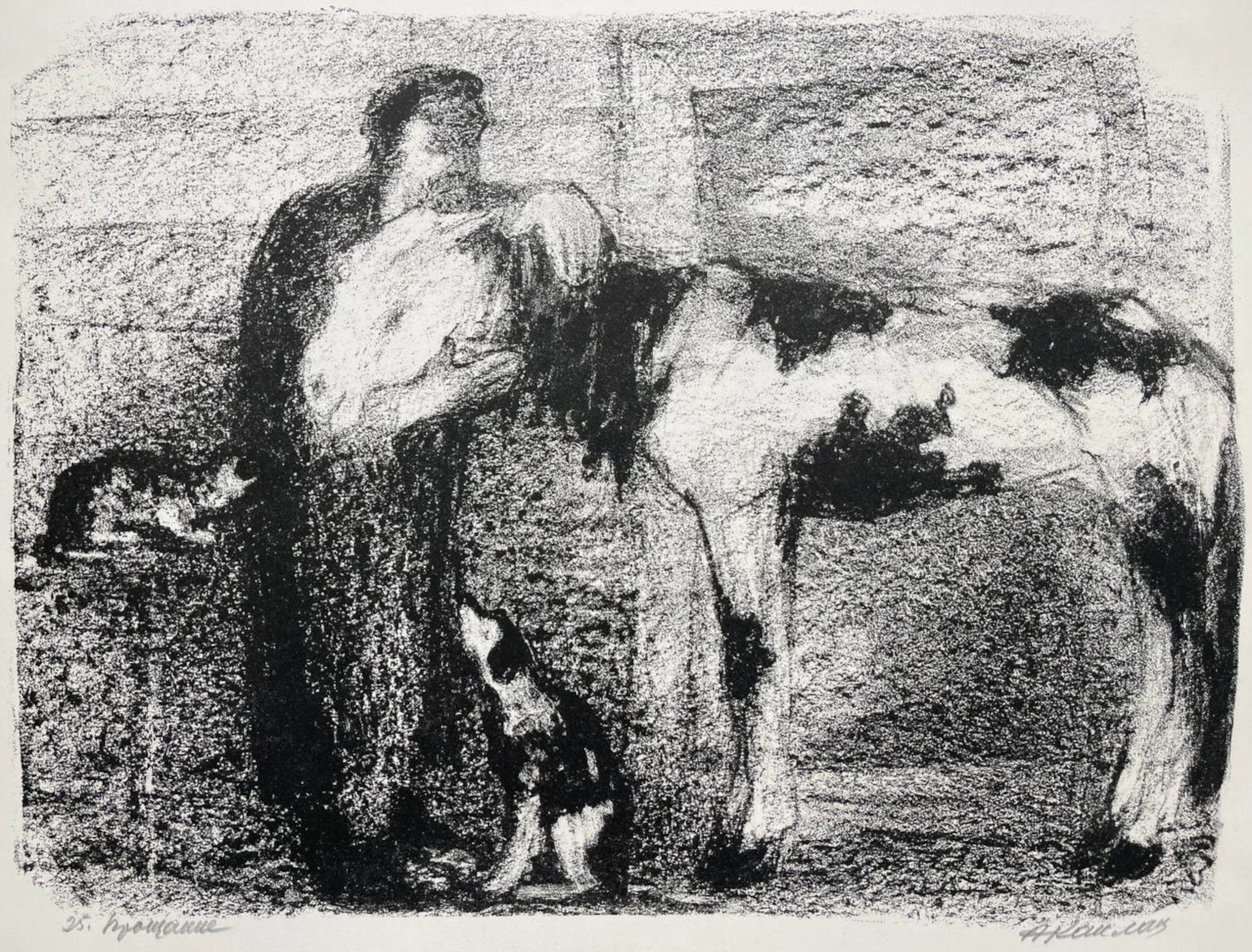

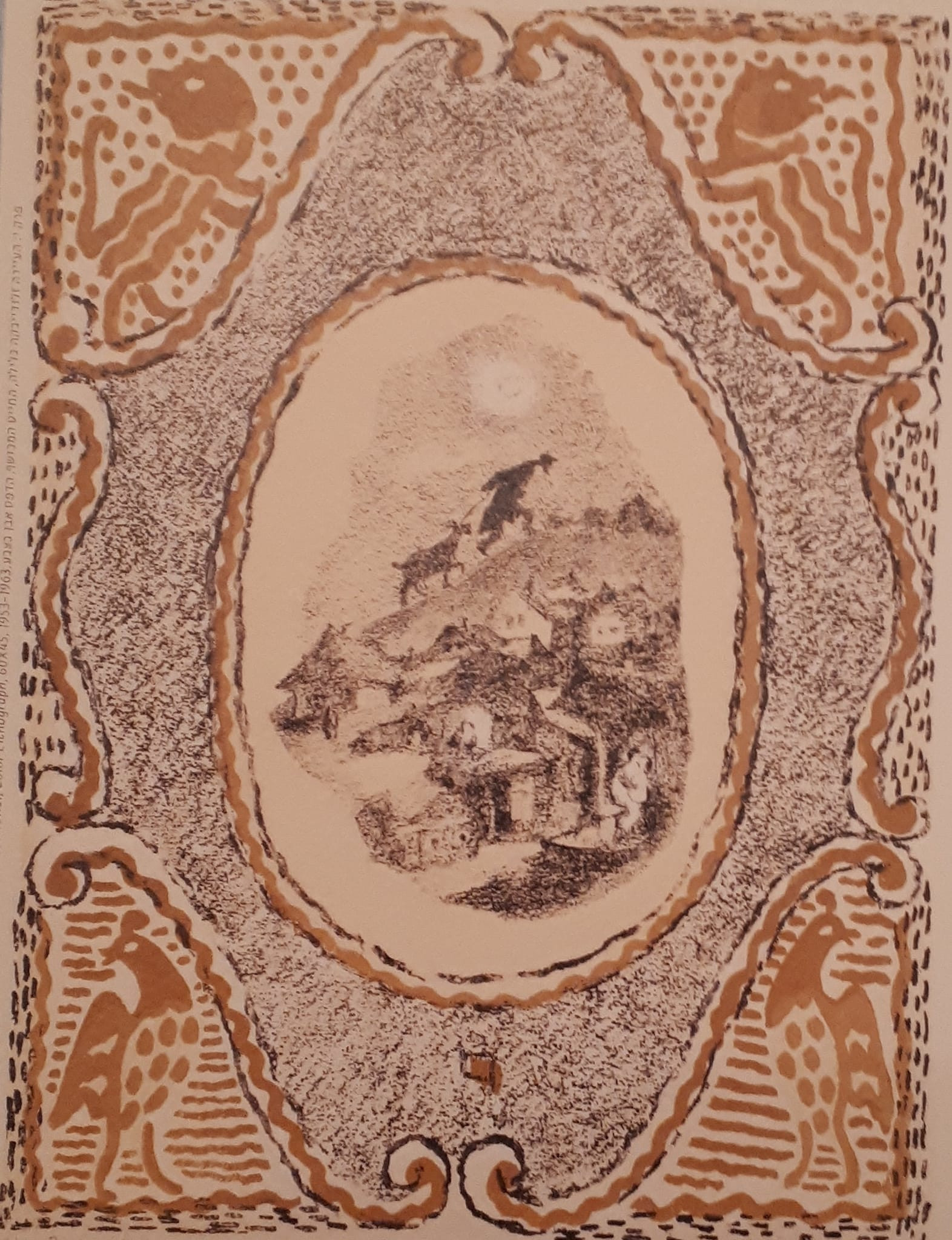

Issachar Ber Ryback

At the turn of the 20th century, painting, sculpture and other visual arts had become an integral part of the national Jewish culture. This happened largely due to the influence of the new Jewish literature, primarily written in Yiddish, which served as a sensitive indicator of all cultural and ideological tendencies. Literature stimulated further developments in all areas of national culture, including arts.

The new Jewish literature began to define high aesthetic standards. It also created a national artistic environment, which united representatives of all creative professions. Before WWI, Jewish authors and artists were already united around common aesthetic and national ideas. Painters and sculptors who belonged to this literature-oriented milieu began to view themselves as the creators of a new national culture.

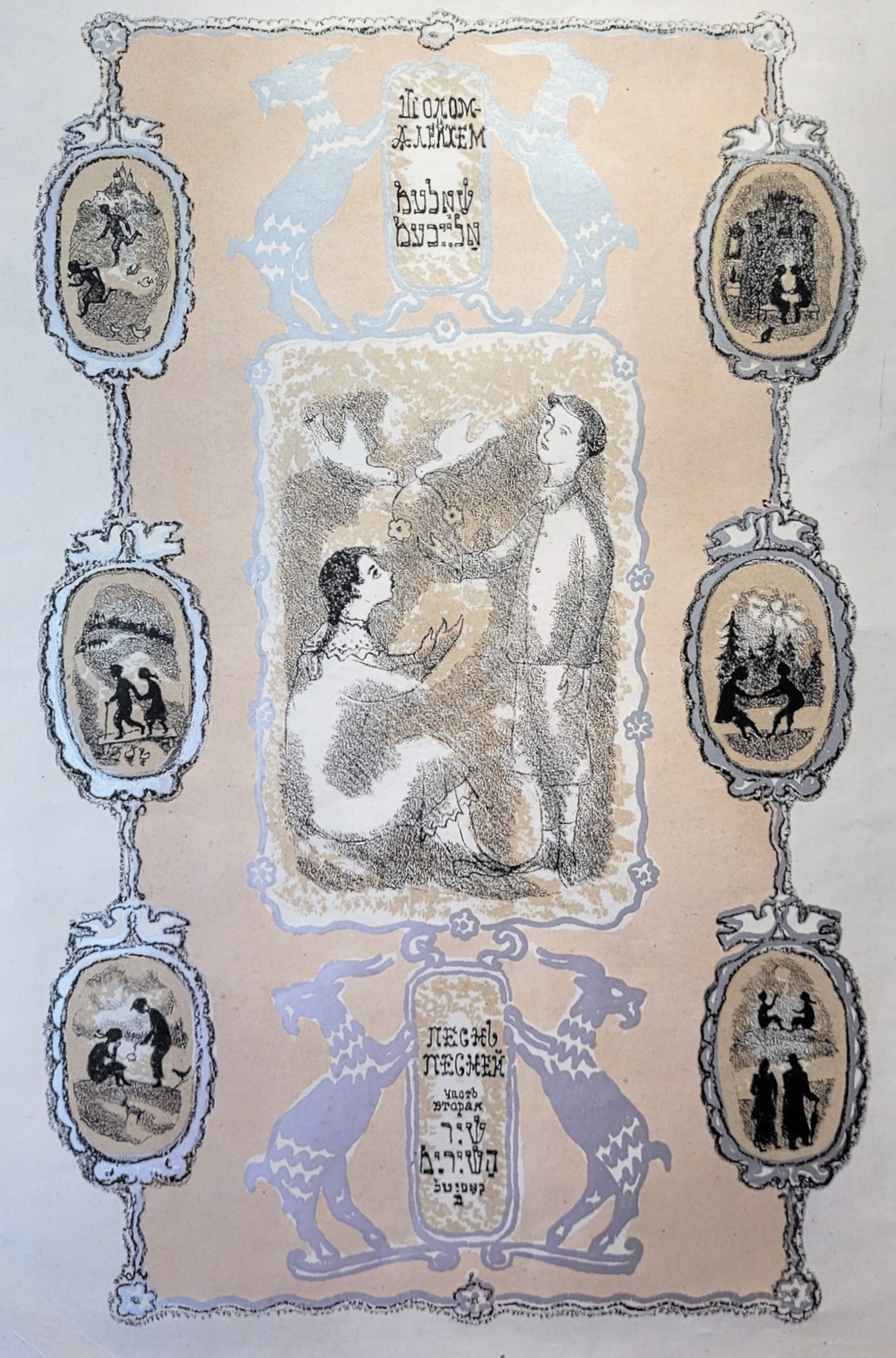

Leo Koenig (1889-1970), one of the members of the first Jewish modernist group Makhmadim, which arose in Paris in 1911, wrote in his memoirs about this group: “… we wanted to show the world our new Jewish motifs and forms (…) Zionist congresses, the Bund, the great Jewish classics were still alive… A generation of Jewish artists appeared, who no longer had to flee from the “ghetto”, from the Jewish life, in order to become painters and sculptors (…), organically linked to the rejuvenated Jewish word, who knew Peretz, Sholem Aleichem, Mendele Moykher-Sforim (…) It was the time when young Jewish painters, mostly from the Pale of Settlement, boldly dreamed of a Jewish form, of stained-glass windows for new Jewish synagogues (…)”

In Koenig’s biography literature played a crucial role too. Shortly after the collapse of Makhmadim, he switched his career and, instead of a painter, soon became a famous essayist, one of the pioneers of Yiddish art criticism.

It is not a coincidence that Yitskhok Leybush Peretz played an extremely important role in the process of incorporating visual arts into the framework of the new national Jewish culture. Peretz was one of the first to see the need to actualize the creative potential of Yiddish folklore and the unique heritage of Eastern European Jewry. He theoretically substantiated his idea and embodied it in his own works.

Young Jewish artists found Peretz the most attractive of all Yiddish classic writers. He was a mentor and a spiritual leader not only for a whole generation of Jewish writers, but also for many artists. Peretz’s inner circle, established in Warsaw a few years before WWI, included such painters as Maurycy Minkowski (1881-1930), Szymon-Ber Kratka (1884-1960, aka Bernard Kratko) and Moishe Appelbaum (1887-1931).

Inspired by Peretz, these and several other artists from his circle became interested in Jewish folk art and traveled across various places in Poland, searching for ancient Jewish ritual objects and traditional clothes, copied the carved reliefs of Jewish tombstones and murals of ancient synagogues. Some if these artists — in particular, Appelbaum — later became synagogue painters themselves. Even S. Ansky, who at one time was far from Jewishness, admitted that Peretz influenced him to “return” to his people. He started writing in Yiddish, became a collector and researcher of Jewish folklore and “Jewish art antiquity”, as well as the founder of the Jewish Museum in Petrograd (1916). This collection, assembled by Ansky, proved to young artists the great value of the traditional Jewish visual culture, which became the basis for their search for aesthetic ideals and creative originality.

Almost all Jewish modernist art groups that emerged in various centers of Ashkenazi Jewish culture on the eve or after WWI were associated with or led by Yiddish writers’ associations. The Yiddish writer and playwright Dovid Ignatov (1885-1954), one of the founders of Di Yunge, a major group of young Yiddish authors based in New York, believed that cooperation with artists is indispensable for the proper development of “young” Jewish literature. Ignatov hoped that the publications of their group would “become an outlet not only for young Jewish writers, but also for artists”.

Di Yunge enjoyed the cooperation of many Jewish American artists, including Zuni Maud (1896-1956), Yitzchok Lichtenstein (1883-1971; also one of the Makhmadim members), Max Weber (1881-1961), Abraham Walkowitz (1878-1965), Abbo Ostrowsky (1899-1963), Benjamin Kopman (1887-1965) and Jennings (Yehuda) Tofel (1891-1959). Their works were reproduced on the pages of the group’s publications, where their own literary experiments were also published (in Yiddish).

Kiev was another cultural center of the Ashkenazi diaspora, where young Jewish artists were also associated with a circle of Yiddish modernist writers, led by Dovid Bergelson, Der Nister, Yekhezkl (Khatskl) Dobrushin and Nakhmen Mayzil. Soon after its establishment, this circle grew into the Kiev Group, which became a prominent phenomenon in the history of modern Yiddish literature. The aesthetic and national cultural ideals of this group had a strong influence on young Jewish artists who studied in Kiev before WWI: Isaac Rabinovich (1894-1961), Mark Epshtein (1899-1949), Issachar Ber Ryback (1897-1935), Borukh (Boris) Aronson (1898-1980), Nisson Shifrin (1891-1962), Alexander Tyshler (1898-1980), and others.

In 1918, this group took an active part in the Kultur-Lige, an organization whose goal was the development of Jewish culture in Yiddish. In one of its first foundational documents, the League outlined three main areas of its activity: “The Kultur-Lige stands on three pillars: Jewish public education, Jewish literature and Jewish art”. Art was defined as one of the most important national and cultural priorities, on par with such a fundamental attribute of Jewish culture as education, which played the central role in the organization’s practical work.

The Kiev Group and its associate artists formed the Literary and Art sections of the Kultur-Lige. Yekhezkl Dobrushin, a Yiddish writer known as an art and literary critic, was elected as the chairman of the Art Section. Dobrushin created original theories of modern Jewish art and Jewish illustrated books. Besides the original Kiev artists, the Art Section included Joseph Chaikov, Polina Khentova, Sarah Shor and Eliezer (El) Lissitzky who arrived in Kiev at the end of 1918.

In 1920, after the establishment of Soviet power in Ukraine, many Jewish artists left Kiev and moved to Moscow, where the Art Section of the Kultur-Lige was also formed and, in addition to most of its Kiev participants, also included Marc Chagall (1887-1985), David Shterenberg (1881-1948) and Nathan Altman (1889-1970). Thus, the organization had united together all the major Jewish artists of the former Russian Empire who viewed creating contemporary avant-garde Jewish art as their main task.

Lodz emerged as a another prominent center of the Jewish artistic avant-garde almost simultaneously with Kiev and Moscow. At the end of 1918, the Yiddish poet Moishe Broderzon (1890-1956), himself a talented painter, theater director and a charismatic leader, initiated the gathering of local Jewish writers and artists who were close to the Polish versions of futurism and expressionism. Among the artists included in the group, called Yung Yidish, were Jankel Adler (1895-1949), Marek Szwarc (1892-1958), Yitskhok (Wincenty) Brauner (Broyner; 1887-1944) and Henryk (Henoch) Barczyński (1896-1941).

The composer Henoch Kohn (1890-1972) and the Warsaw artists Henryk Berlewi (1894-1967) and Zeev Wolf (Wladislaw) Weintraub (1891-1942) also collaborated with Yung Yidish. The group was a radical experiment in creative avant-garde synthesis, equally combining elements of poetry and graphic arts. The group’s almanacs, which included a subsection titled “Lider in vort un tseykhnungen” (“Poems in word and drawings”), were a vivid evidence of this synthesis, illustrating the desire to blur the boundaries between the visual and the verbal realms.

Since the new Jewish art and the Yiddish language were intrinsically linked together, these interwar modernist art groups arose in every major center of Yiddish culture. In Riga, the writer group Sambatyon was headed by the artist and art theorist Michael Io (Ioffe; 1893-1960). In London, Leo Koenig created the Renaissance group, which attracted such local Jewish writers and artists as David Bomberg (1890-1957) and Jacob Kremer (1892-1962).

The Chicago futurist group Yung Tshikago, which included the outstanding poet Mates Deitch (1894-1966) and the artist Todres Geller (1889-1949), was founded in the mid-1920s. In 1929, the literary group Yung Vilne appeared in Vilna. One of its leaders was the great poet Avrom Sutzkever (1913-2010). His sister Rokhl Sutzkever (1909-1941) and Benzion Mikhtom (1909-1941) were two painters who became full members of the same group.

In the early 1930s, similar Jewish artistic circles arose in Buenos Aires and even in Johannesburg. Thus, much like the Yiddish literature and culture in general, Jewish art had reached an international scale and a worldwide distribution.

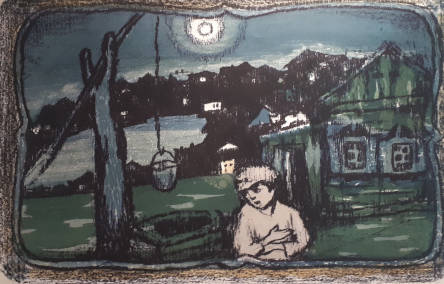

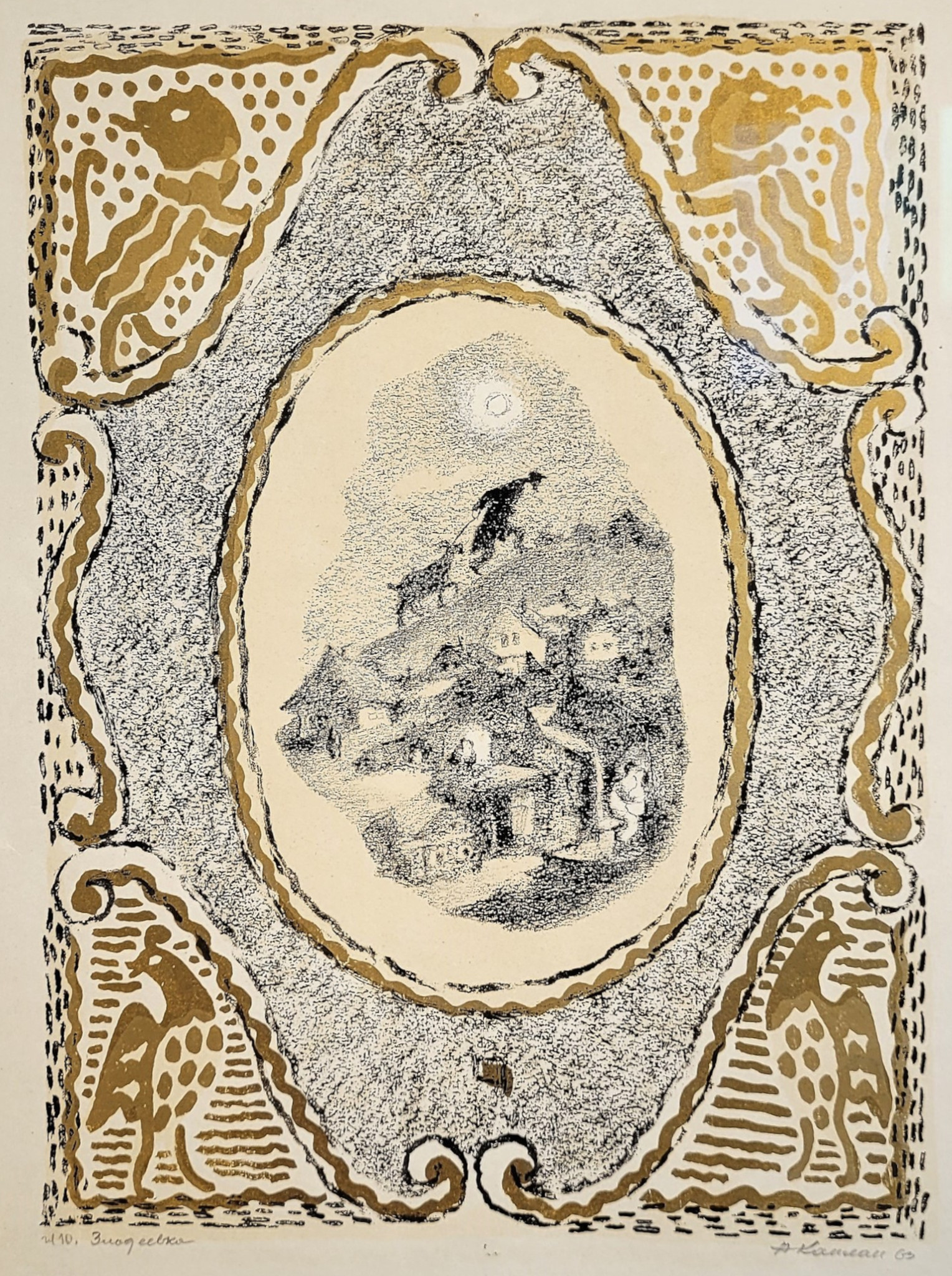

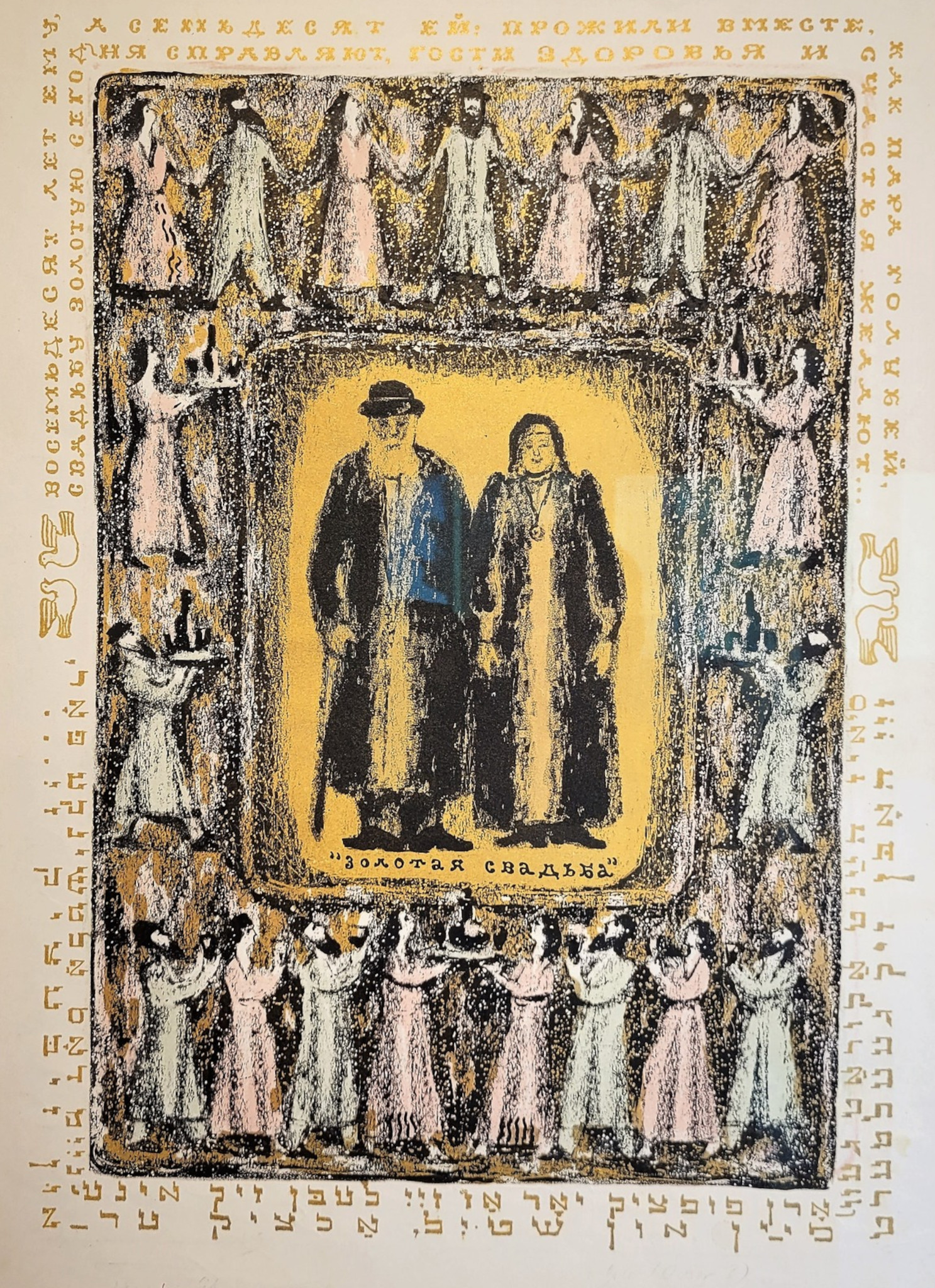

After WWII, links to Yiddish and Yiddish literature continued to stimulate the creativity of Jewish artists in different countries. Examples include Hersh Inger, Anatoli (Tankhum) Kaplan, Meer Axelrod, Yuri Kuper and Mikhail Grobman in the USSR; Maurice Sendak and Siegmunt Forst in the US; Yosl Bergner in Canada and Israel.

As we see, many of the greatest 20th century world famous artists were in various ways connected to Yiddish and its culture. The language itself had become a foundational element in the works of some of them. In particular, quite a few of Marc Chagall’s paintings are visualizations of Yiddish expressions. Yiddish was also a very important vehicle of artistic thoughts and theory: many avant-garde manifestos, brilliant critical articles and essays on art were written in this language. Some fundamental and innovative ideas of artistic development were formulated for the first time in Yiddish, before spreading in the worldwide theory of art.

Hillel Kazovsky