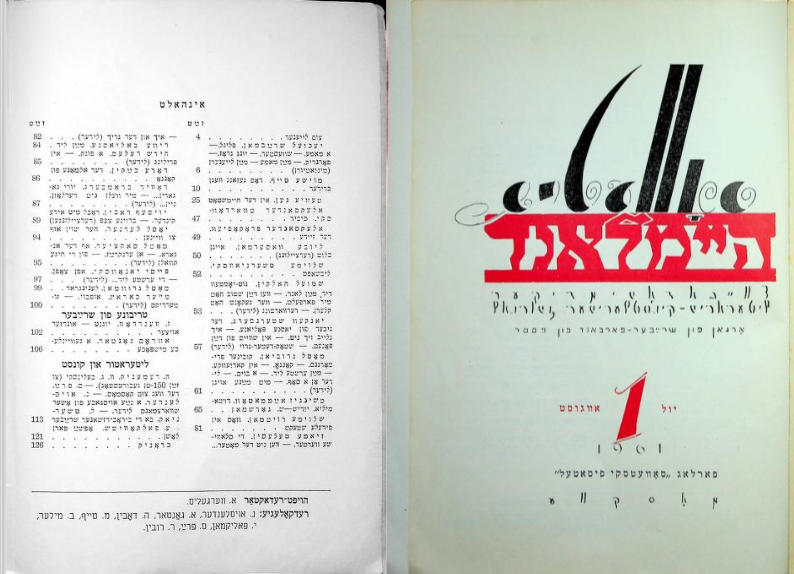

The legendary magazine Sovetish Heymland (סאָוועטיש הײמלאַנד, “Soviet Motherland”) was a Soviet literary and artistic Yiddish magazine, officially published by the Writers’ Union in Moscow from 1961 to 1991. It was the only Jewish magazine in the Soviet Union after WWII. After being closed due to the collapse of the USSR, it was briefly revived in 1993 under the name Di Yidishe Gas (די ייִדישע גאַס, “The Jewish Street”). The publication was finally discontinued after the death of its permanent editor-in-chief Aron Vergelis (1918 — 1999). For a number of historical reasons, this magazine played and, thanks to its unique cultural heritage, continues to play a key role in the development of modern Jewish literature and Yiddish culture.

In 1948, the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was liquidated and its members were executed on August 12, 1952. In the same time period, the Moscow GOSET and the last Yiddish schools in the USSR were closed. The remnants of the official Soviet Jewish culture were preserved only in the Jewish Autonomous Region — primarily in the form of the newspaper Birobidzhaner Shtern (ביראָבידזשאַנער שטערן). Its publication had never ceased since its founding in 1930. After a long break of almost ten years, the Jewish writer, poet, publicist and public figure Aron Vergelis managed to “break through” the highest spheres of the Soviet leadership and create a new Yiddish magazine: Sovetish Heymland.

In 1948, the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was liquidated and its members were executed on August 12, 1952. In the same time period, the Moscow GOSET and the last Yiddish schools in the USSR were closed. The remnants of the official Soviet Jewish culture were preserved only in the Jewish Autonomous Region — primarily in the form of the newspaper Birobidzhaner Shtern (ביראָבידזשאַנער שטערן). Its publication had never ceased since its founding in 1930. After a long break of almost ten years, the Jewish writer, poet, publicist and public figure Aron Vergelis managed to “break through” the highest spheres of the Soviet leadership and create a new Yiddish magazine: Sovetish Heymland.

In its very first issue, Vergelis, who had become its editor-in-chief, promised that the magazine would “reflect at a high level the most important problems of our time.” The chosen name of the periodical, despite all its Soviet pretentiousness, emphasized the continuity with two previous Moscow Yiddish periodicals: the prewar almanac Sovetish and the short-lived postwar Heymland. In its first years, the magazine was published once every two months; it became a monthly since January 1965.

Vergelis kept his promise. Despite censorship and the fact that after the war much fewer people were able to read Yiddish, the magazine remained one of the highest quality periodicals in the country throughout all the years of its existence. This is true regarding both its literary and art content. In addition to prose, poetry and literary criticism, Sovetish Heymland published unique academic works on Jewish folklore and history, Yiddish language and literature, etc. It also featured the musical section “לאָמיר זינגען נײַע לידער” (“Let’s sing new songs”), which contained scores for Yiddish songs by famous composers. Readers even had the opportunity to familiarize themselves (in translation) with some classical religious and philosophical texts in Hebrew and Aramaic, which was an extreme rarity for a non-specialized publication in the USSR.

Vergelis kept his promise. Despite censorship and the fact that after the war much fewer people were able to read Yiddish, the magazine remained one of the highest quality periodicals in the country throughout all the years of its existence. This is true regarding both its literary and art content. In addition to prose, poetry and literary criticism, Sovetish Heymland published unique academic works on Jewish folklore and history, Yiddish language and literature, etc. It also featured the musical section “לאָמיר זינגען נײַע לידער” (“Let’s sing new songs”), which contained scores for Yiddish songs by famous composers. Readers even had the opportunity to familiarize themselves (in translation) with some classical religious and philosophical texts in Hebrew and Aramaic, which was an extreme rarity for a non-specialized publication in the USSR.

The magazine was also notable for its color pages with rare works of famous painters. The selection of illustrations was carried out by Sofia Chernyak (1904 – 2022), a long-term member of the editorial board and a major researcher of Jewish art. She introduced a whole range of 20th century painters who stood out from the line of “official” masters recognized by the Soviet censorship. It should be noted that Sovetish Heymland was the first magazine in the USSR to publish the works of Marc Chagall in 1968.

The magazine’s editorial board collected bio-bibliographic materials about Yiddish writers; its office created a large library of Jewish books, reference works and archival documents. Thus, Sovetish Heymland became a major global center for the development of Jewish literature, which stimulated literary creativity in Yiddish and the study of Yiddish classics, including victims of Stalin’s purges. The office held Jewish-themed conferences, musical and literary art evenings, painting exhibitions and other cultural events (of course, strictly within the framework of Soviet ideology).

The editorial board of the magazine included such famous authors as the outstanding novelist Note Lurye, nicknamed the “Jewish Sholokhov”, poets Hirsh Osherovich, Moyshe Teyf, Avrom Gontar, Chaim Beyder, etc. The listing of hundreds of authors whose works were published in the magazine is beyond the scope of this introductory article: these include almost all famous Jewish Soviet writers, and a substantial number of authors from other countries. The numerous translations of prose and poetry from different languages into Yiddish are also of great interest.

From the 1980s, Sovetish Heymland began to publish a series of supplements, such as brochures with Yiddish lessons, poems by young authors, a small dictionary and other educational materials. The large 1984 Russian-Yiddish Dictionary was also published with the direct support of the magazine’s editors, including Vergelis.

From the 1980s, Sovetish Heymland began to publish a series of supplements, such as brochures with Yiddish lessons, poems by young authors, a small dictionary and other educational materials. The large 1984 Russian-Yiddish Dictionary was also published with the direct support of the magazine’s editors, including Vergelis.

On the occasion of the twentieth anniversary of Sovetish Heymland, in 1981, the Soviet Writers’ Union decided to start a Jewish group, led by Vergelis, at the Higher Literary Courses of the Maxim Gorky Literary Institute. This was the only educational program in the postwar world geared for young Yiddish authors.

Three of the five students of the first group subsequently became world famous: Boris Sandler, Lev Berinsky and Velvl Chernin. In 1998, Sandler became the head the world’s oldest Yiddish newspaper, the Forverts (Yiddish Forward) in New York. Thanks to his activities, the newspaper adopted many stylistic and genre features stemming from Sovetish Heymland, while constantly publishing former authors of this magazine. Since 2017, Sandler has been running the online literary magazine Yiddish Branzhe.

In 2018, Velvl Chernin and Mikhoel Felsenbaum (whose first works also appeared in Sovetish Heymland), created the literary quarterly Yidishland, which is published in two circulations in Israel and Sweden. Thus, Vergelis pupils, then young authors, as the editor dreamed, continue to play a very significant international role in Yiddish culture, including contemporary literary Yiddish periodicals. Several years ago, Aron Vergelis’ widow Evgenia Katayeva donated his personal collection of books and documents to the Moscow Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center, while the archives of Sovetish Heymland were transferred to the Moscow Jewish publishing house Knizhniki, which is closely associated with the museum.

The Sovetish Heymland digitization is carried out by the Heritage Project Foundation (USA) and the Yiddish Culture Preservation Foundation (Israel) on the initiative of their founder, Dr. Mark Zilberquit. The project’s partner is the Moscow publishing house Knizhniki. Financial assistance is provided by Academician Grigory Roitberg, the Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Russian Jewish Congress.

The digitization and publication of the magazine’s full archive on the Internet is planned to be completed in the second half of 2024. This initiative is part of a general project for the preservation of Yiddish culture, which is carried out by the two aforementioned foundations. All related materials will be published exclusively on this website and other online resources officially associated with us.

In 1948, the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was liquidated and its members were executed on August 12, 1952. In the same time period, the Moscow GOSET and the last Yiddish schools in the USSR were closed. The remnants of the official Soviet Jewish culture were preserved only in the Jewish Autonomous Region — primarily in the form of the newspaper Birobidzhaner Shtern (ביראָבידזשאַנער שטערן). Its publication had never ceased since its founding in 1930. After a long break of almost ten years, the Jewish writer, poet, publicist and public figure Aron Vergelis managed to “break through” the highest spheres of the Soviet leadership and create a new Yiddish magazine: Sovetish Heymland.

In 1948, the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was liquidated and its members were executed on August 12, 1952. In the same time period, the Moscow GOSET and the last Yiddish schools in the USSR were closed. The remnants of the official Soviet Jewish culture were preserved only in the Jewish Autonomous Region — primarily in the form of the newspaper Birobidzhaner Shtern (ביראָבידזשאַנער שטערן). Its publication had never ceased since its founding in 1930. After a long break of almost ten years, the Jewish writer, poet, publicist and public figure Aron Vergelis managed to “break through” the highest spheres of the Soviet leadership and create a new Yiddish magazine: Sovetish Heymland. Vergelis kept his promise. Despite censorship and the fact that after the war much fewer people were able to read Yiddish, the magazine remained one of the highest quality periodicals in the country throughout all the years of its existence. This is true regarding both its literary and art content. In addition to prose, poetry and literary criticism, Sovetish Heymland published unique academic works on Jewish folklore and history, Yiddish language and literature, etc. It also featured the musical section “לאָמיר זינגען נײַע לידער” (“Let’s sing new songs”), which contained scores for Yiddish songs by famous composers. Readers even had the opportunity to familiarize themselves (in translation) with some classical religious and philosophical texts in Hebrew and Aramaic, which was an extreme rarity for a non-specialized publication in the USSR.

Vergelis kept his promise. Despite censorship and the fact that after the war much fewer people were able to read Yiddish, the magazine remained one of the highest quality periodicals in the country throughout all the years of its existence. This is true regarding both its literary and art content. In addition to prose, poetry and literary criticism, Sovetish Heymland published unique academic works on Jewish folklore and history, Yiddish language and literature, etc. It also featured the musical section “לאָמיר זינגען נײַע לידער” (“Let’s sing new songs”), which contained scores for Yiddish songs by famous composers. Readers even had the opportunity to familiarize themselves (in translation) with some classical religious and philosophical texts in Hebrew and Aramaic, which was an extreme rarity for a non-specialized publication in the USSR.

From the 1980s, Sovetish Heymland began to publish a series of supplements, such as brochures with Yiddish lessons, poems by young authors, a small dictionary and other educational materials. The large 1984 Russian-Yiddish Dictionary was also published with the direct support of the magazine’s editors, including Vergelis.

From the 1980s, Sovetish Heymland began to publish a series of supplements, such as brochures with Yiddish lessons, poems by young authors, a small dictionary and other educational materials. The large 1984 Russian-Yiddish Dictionary was also published with the direct support of the magazine’s editors, including Vergelis.