Velvl Chernin: Theater

Exhibits and Performances

Exhibits and Performances

The Bird Alef From the Old Gramophone

The Bird Alef

From the Old Grammophone

Song lyrics and libretto by Boris Sandler

Music by Evgeny Kissin

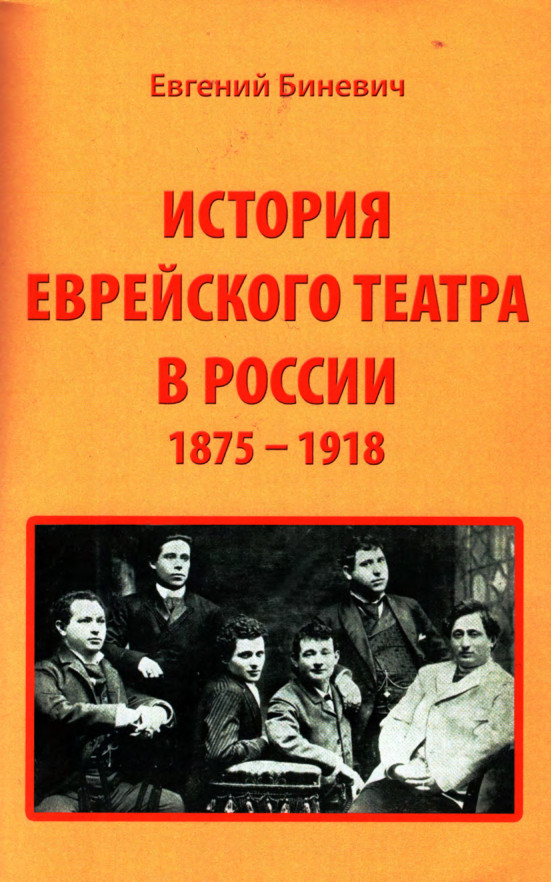

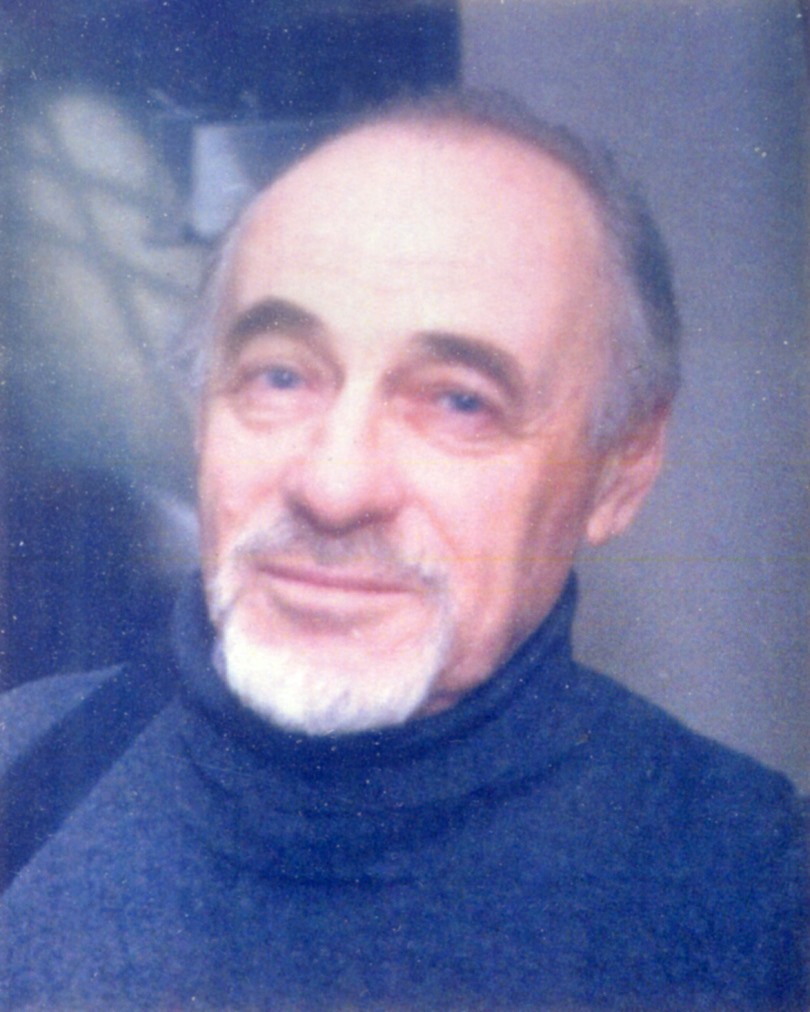

Evgeny Binevich

Evgeny Binevich:

Book and Its Author

The way this book was created and what happened many years after its publication is somewhat unusual.

More than ten years ago, my Soviet-born friend Alexander Dranov who has been living in the US since the 1970s and works as a lawyer, called me and asked me to help him publish a book about the history of Jewish theater in Russia.

Alexander himself, although he chose a law career, always was unusually artistically inclined his life, which may have to do with genetics: both of his grandfathers and grandmothers were famous Jewish actors who had shining, albeit difficult lives and stage careers.

Evgeny Binevich

Of course, neither he nor I could have possibly known them. However, I very well knew Alexandrov Dranov’s mother: Rosa Kurtz, the former actress of Solomon Mikhoels’ Moscow State Jewish Theater (GOSET) who went through severe hardships in her life. After the theater’s closure, she had to take care of her chronically ill husband who was confined to bed and then had to wander across faraway Soviet places with Vladimir Shvartser’s troupe; he created the Jewish Theater Ensemble on the ruins of GOSET.

She then emigrated to the US. I was impressed by the huge cover article in a Houston newspaper (it is where the Dranov family had emigrated from Soviet Russia) with the large title “Jewish Theater Comes to Houston”. This was an enthusiastic review of Rosa Kurtz’s solo performance with excerpts from plays and songs in Yiddish.

This time it was a different matter though. Alexander Dranov told me that he was contacted by Evgeny Binevich, a well known theater critic who lived in Saint Petersburg, Russia, and was writing at that time a profound monograph on the history of Russian Jewish theater. Binevich gave Dranov access to his entire extremely rich family archive. Knowing that I was already a publisher at that time, my friend appeal to me and I helped him to release the book.

For a very long while I did not think of this story and then, a year ago, I was unable to fall to sleep after returning to America and took a random book from the shelf to entertain myself. That was Evgeny Binevich’s “History of Jewish Theater in Russia: 1875-1918”. I opened it, read Alexander Dranov’s grateful autograph on the back cover and paged through the selection of numerous archival photographs in the final part.

Precisely at that time, I was starting to develop my project for the preservation of Yiddish culture. The theme of the book I’ve randomly opened was directly related to it. The next morning I called Dranov. At that time, I had not been in contact with him for a long while. The very next day we were dining at one of New York restaurants. After the usual quick words of politeness, I told him about my project and turned to questions that interested me very much.

It turned out that he still had his family archive safe and intact. Moreover, after his mother’s death he unexpectedly discovered her hitherto unknown and, obviously, unpublished memoirs. I could barely hide my excitement and joy when he said that all rights to Binevich’s book belong only to him and to the author, and that he conveys those rights together with the memoirs of his mother, Rosa Kurtz, with his preface for the first publication on this website dedicated to my project.

But that is not the end of the story.

Returning home from the dinner, I opened the address book on my phone and found Evgeny Binevich. Fortunately, I never delete any numbers once entered.

When I dialed the number, I heard a woman’s voice. That was the author’s daughter Valeria who said that her father passed away two years ago. It turned out that she had heard about me from her father, who, according to her, was grateful to me for helping him to publish the book. Then she asked me if I was going to St. Petersburg, because her father left a huge archive and she did not know what to do with it.

A few months later, I went to St. Petersburg and visited Valeria Binevich. When she found out that I intended to place her father’s book as one the first and most important materials on this new website dedicated to Yiddish culture (see the Theater section), she said that she would give me her father’s entire archive for my work, free of charge. This was an invaluable gift, which will undoubtedly help to perpetuate the memory of this true knight of art and, specifically, of the Jewish theater.

Together with the archive, Valeria gave me a tiny brochure with a more than modest title: “Evgeny Binevich. Bibliography”. A formal list of his published works, as befits a bibliographic reference, ended with a brief but incredibly poignant autobiographical sketch. Here I am quoting a few excerpts from it. The last lines are especially heartbreaking.

“… The life is ending… Will there be enough time to publish anything else? This little brochure, at least?

… Basically, spent the life in humiliating poverty. We did not go hungry, we did not walk around in rags… But even buying my wife a flower or mailing abroad our next publication was always a problem. And we could not afford to have a second child.

… And yet now, near the end, it often occurs to me that I have lived a happy life … I did not write a single opportunistic line. I only wrote about things that I myself was interested in… “

Mark Zilberquit

Faust Mindlin

Faust Mindlin

My Jewish Actors (Russian)

Faust Mindlin

His grandfather, Joseph Mindlin, was an actor and director of Yiddish theaters. With the assistance of Marc Chagall, he created the first Jewish professional workers’ theater in Vitebsk. He also worked as a director and actor of Yiddish theaters in Kiev, Kharkov, Odessa, Smolensk, Baku. After the closure the Odessa Jewish theater, Joseph Mindlin was arrested and sent to the Gulag camps. He died shortly after being released from jail and was posthumously rehabilitated in 1989.

Faust Mindlin’s mother, Rita Gendlina, was a Jewish actress who graduated under the direction of Solomon Mikhoels from the school of the Moscow Jewish Theater School (GOSET). She worked in the theaters of Lvov and Odessa.

In his series of essays, which cover the history of the Odessa Jewish theater from 1917 till 1949, including its descrtuction, Mindlin also reconstructs hitherto unknown historical details of the Jewish theater movement in the Russian Empire of 1879-1917.

Until very recently, he lived and worked in Odessa, until the tragic circumstances of the war in Ukraine forced him to move to America.

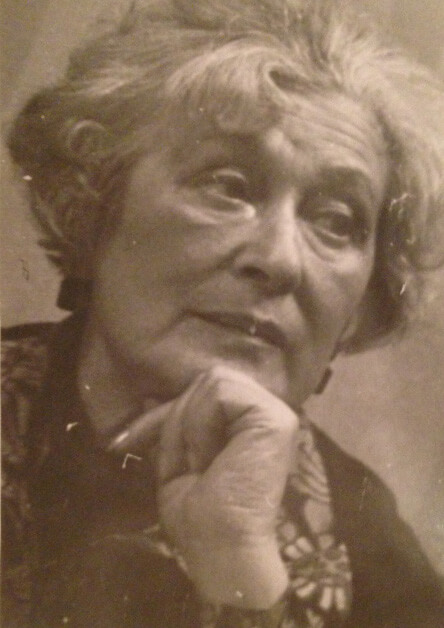

Rosa Kurtz

Rosa Kurtz and Her

Long Difficult Life

During its short existence, the Moscow State Jewish Theater (GOSET) gained its fame not only thanks to its genious directors who were also brilliant actors – Mikhoels and Zuskin – but thanks to many other great artistric names as well.

One of them was Rosa Kurtz (1908-2003). Born in the early 20th century into a family of Jewish actors, she herself lived a long and very difficult life as a “wandering star”.

Rosa Kurtz

Rosa Kurtz received her education at the GOSET theater studio that opened in 1929. In 1931 she joined the GOSET’s troupe and was on the stage of this famous theater up until its closure in 1950. Then she faced difficult years without having work.

The situation was aggravated by the fact that her husband, the lawyer Boris Dranov, who also stemmed from a family of Jewish actors, was bedridden due to a terrible illness. Rosa Kurtz met the ends by making artificial flowers.

In 1961, during the Khrushchev Thaw, Vladimir Shvartser created the Jewish Theater Ensemble and Rosa once again took the stage and began wandering across Russia, often experiencing inconveniences in far away places. At least, the theater work provided her with some income and she had the opportunity to successfully perform with her troupe in front of a Jewish audience – in Yiddish, of course!

In 1978, Rosa Kurtz, after having received the award as a “shock worker of communist labor” (how ironic!), emigrated to the United States with her son and his family. Despite her age, she began to give concerts, playing little scenes from Yiddish performances and singing Yiddish songs. One article in a Houston newspaper, preserved in her family archive, was entirely dedicated to her performances and headlined with huge letters: “The Jewish Theater Comes to Houston.”