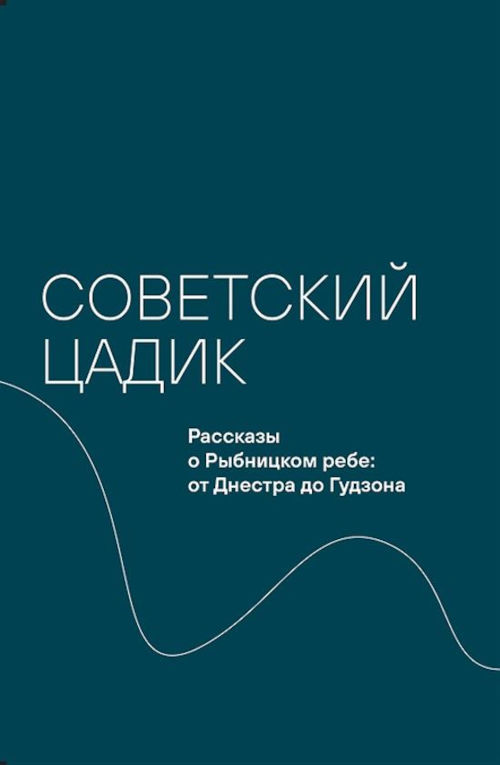

The Moscow publishing house Kuchkovo Polye released a new Russian book titled The Soviet Tzaddik. Stories about the Ribnitzer Rebbe: from the Dniester to the Hudson River, edited by Dr. Valery Dymshits, Dr. Maria Kaspina and Dr. Alexandra Poljan. Rather than focusing on the Ribnitzer Rebbe as a historical personality, the monograph explores the rich folkloric material surrounding this figure, largely collected from contemporary Hasidic materials written in Yiddish. It is the first major academic study of this subject.

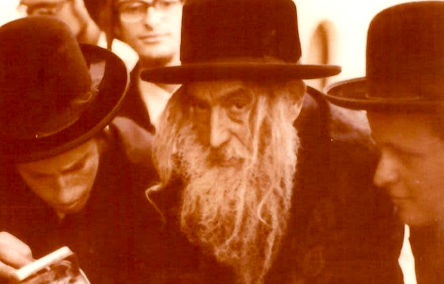

Chaim Zanvl Abramowitz (1902 ? – 1995), known as the Ribnitzer Rebbe, is considered one of the greatest 20th century Hasidic leaders, reputed as a miracle worker who maintained an extraordinary ascetic lifestyle. He managed to live a fully Jewish religious life in the USSR; soon after his emigration to Israel in 1970 and a few years later to the United States he became a living legend among Yiddish-speaking American Hasidim. The Ribnitzer Rebbe’s legacy remains a rich source of contemporary Yiddish folklore.

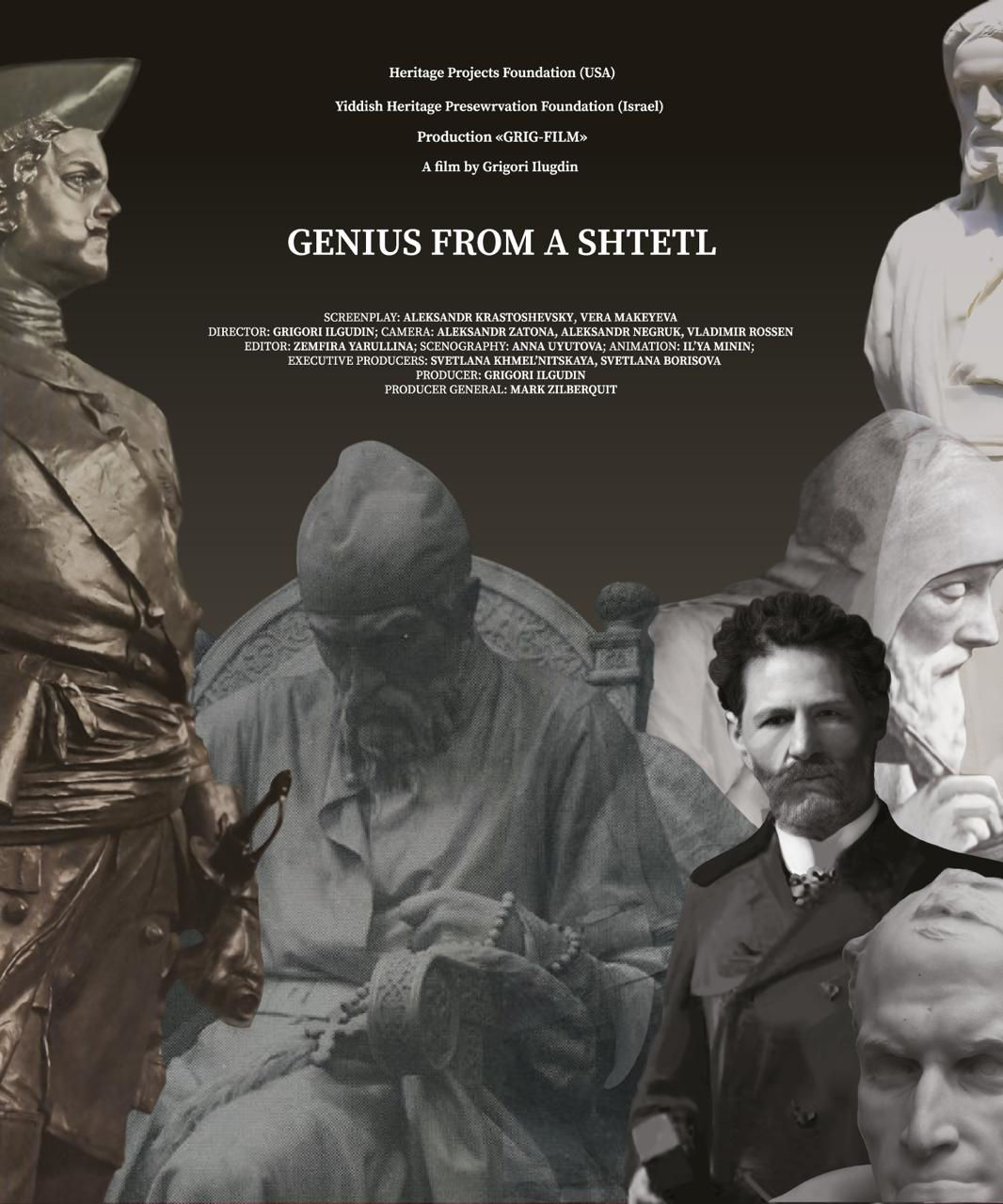

Grigori Ilugdin’s Russian-Yiddish film Genius from a Shtetl, a documentary about the famous sculptor Mark Antokolsky, is now publicly available online with English subtitles. It contains several 3D-animated scenes in Antokolsky’s native Lithuanian dialect of Yiddish. The director expresses his deep gratitude to the Heritage Projects Foundation (USA) and Yiddish Heritage Preservation Foundation (Israel) who supported the documentary.

Grigori Ilugdin’s Russian-Yiddish film Genius from a Shtetl, a documentary about the famous sculptor Mark Antokolsky, is now publicly available online with English subtitles. It contains several 3D-animated scenes in Antokolsky’s native Lithuanian dialect of Yiddish. The director expresses his deep gratitude to the Heritage Projects Foundation (USA) and Yiddish Heritage Preservation Foundation (Israel) who supported the documentary.

חברת הטלוויזיה הרוסית “בירה” הגישה ב-13 בספטמבר 2024

חברת הטלוויזיה הרוסית “בירה” הגישה ב-13 בספטמבר 2024

The Moscow publishing house Kuchkovo Polye released a new Russian book titled The Soviet Tzaddik. Stories about the Ribnitzer Rebbe: from the Dniester to the Hudson River, edited by Dr. Valery Dymshits, Dr. Maria Kaspina and Dr. Alexandra Poljan. Rather than focusing on the Ribnitzer Rebbe as a historical personality, the monograph explores the rich folkloric material surrounding this figure, largely collected from contemporary Hasidic materials written in Yiddish. It is the first major academic study of this subject.

The Moscow publishing house Kuchkovo Polye released a new Russian book titled The Soviet Tzaddik. Stories about the Ribnitzer Rebbe: from the Dniester to the Hudson River, edited by Dr. Valery Dymshits, Dr. Maria Kaspina and Dr. Alexandra Poljan. Rather than focusing on the Ribnitzer Rebbe as a historical personality, the monograph explores the rich folkloric material surrounding this figure, largely collected from contemporary Hasidic materials written in Yiddish. It is the first major academic study of this subject.